© Carnegie Hall Corporation

I am not a great fan of tabloid or boulevard journalism. Surely you have seen these colourful publications at checkout counters in your local supermarket and elsewhere. Most carry outrageous headlines of alien invasions or some poor souls doing something unspeakable to themselves or other. But I must confess, when it comes to love and romance stories involving the rich, handsome and famous, I get all excited. Please don’t blame me. Tales of classical romance are not a new invention, as everybody wanted to know about the love life of yesteryear’s superstar, including classical music composers. So we decided to take a look at the most famous glamour couples in classical music. Get ready for some classical romance involving 10 famous classical music composers.

Gustav Mahler and Alma Schindler:

Gustav Mahler and Alma Schindler

Alma Schindler was Vienna’s most desired bachelorette at the turn of the 20th century, and she knew it. She was utterly obsessed by a sense of entitlement that the world owed her something in return for her brilliance and her beauty. She was well read, highly educated, and an accomplished pianist and composer. Alma was drawn to older men with artistic credentials, intellect, creativity, and money, and she attracted them like flies. Gustav Mahler was engaged as conductor at the imperial opera, and they had a huge argument when they first met at a dinner party. Mahler was conducting an opera of her ex-lover Alexander Zemlinsky, and Alma told him exactly what he should do. They couldn’t agree and met at the opera the following day to iron out their differences. A whirlwind courtship soon ensued, and Gustav proposed marriage on 21 December 1901. The couple was formally married at a private ceremony on 9 March 1902, with Alma already carrying their first child, Maria Anna. The relationship wasn’t a bed of roses, but Mahler composed the famous “Adagietto” from his 5th Symphony as a love song without words for Alma. Classical romance doesn’t get any better than that, don’t you think?

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5, “Adagietto”

Johann Sebastian Bach and Anna Magdalena Wilcke:

Johann Sebastian Bach and Anna Magdalena Wilcke

When Johann Sebastian Bach returned to Cöthen from a lengthy trip to Carlsbad, he was told that his wife Maria Barbara Bach had died at the age of 36. Carl Philip Emanuel reports, “My father returned to find her dead and already buried.” It was a tremendous shock not only to Johann Sebastian, but also to four motherless children. Johann Sebastian dealt with his grief by composing tirelessly, and for special feast days singers from nearby Courts were enlisted to strengthen the local choir. One such singer was Anna Magdalena Wilcke, and a classical romance soon ensued. They were first seen together as godparents at a child’s christening. Bach was 36 and Anna Magdalena 20, and apparently he was attracted by her fine soprano voice, among other things. The couple married on 3 December 1721, and to celebrate the occasion, Bach went twice to the city cellars and bought two small casks of Rhine wine. Anna Magdalena was an accomplished musician and deeply involved in her husband’s musical tasks. To show his appreciation, Johann Sebastian put together a little notebook of music specifically dedicated to his wife. Recently, it has been suggested that it was Anna Magdalena who actually composed some of the pieces in this little notebook. How delightful, two classical music composers and lovers writing music for each other.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Little Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach, Book 2, BWV Anh. 113-132 (Joao Carlos Martins, piano)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Constanze Weber:

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Constanze Weber

Among classical music composers, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart rates as one of the top musical geniuses. And his classical romance with Constanze Weber was definitely a high-profile topic for the tabloid press. Mind you, Mozart’s eye initially fell on Aloysia Weber, Constanze’s sister. She was a well-known soprano and became Mozart’s student and lover. He really wanted to marry her, but his father sent him on a long tour to Paris. When he came back several months later, Aloysia pretended that she didn’t even know him. As you can imagine, Mozart wasn’t particularly happy and he had some choice words for his ex-lover. Her sister Constanze wasn’t even on his radar, but all that changed when he became a lodger in the Weber household in Vienna. Mozart wanted to stay for only a week, but as he fell in love with 19-year-old Constanze, he stayed for several months. Her mother wasn’t happy about the courtship and neither was Mozart’s father. The couple broke up for a short period of time but got married on 4 August 1782 at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. Mozart writes to his father, “Tell me whether I could wish for a better wife.” Constanze was a trained singer, and her husband wrote several compositions specifically for her clear soprano voice.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Great Mass in C minor

Ludwig van Beethoven and Therese Malfatti:

Ludwig van Beethoven and Therese Malfatti

Ludwig van Beethoven wasn’t lucky in love. I think it was actually his own fault. He kept falling in love with women of high social standings, or women already married to somebody else. And let’s not forget the countless times he fell in love with his beautiful and young students. Therese Malfatti was 18 and Ludwig 40, and it seems that he mistook her admiration and devotion to be love. Beethoven was actually serious about marrying Therese, because he asked a good friend to forward his birth certificate from Bonn, which would have been required for marriage. An anecdote tells of the story when Beethoven was invited to the Malfatti household in 1810 to a cocktail party. Beethoven apparently wanted to propose to Therese and composed a special bagatelle for her. In the event, Beethoven got seriously drunk and forgot all about playing or proposing. He never summoned the courage to ask for her hand in marriage again, and Therese married an Austrian nobleman in 1816. Beethoven writes, “Now fare you well, respected Therese. I wish you all the good and beautiful things of this life. Bear me in memory—no one can wish you a brighter, happier life than I—even should it be that you care not at all for your devoted servant and friend.” How is that for a classical romance that never was?

Ludwig van Beethoven: Bagatelle No. 25 in A minor “Für Elise” WoO 59

Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck:

Robert and Clara Schumann, 1847

Among classical music composers, the love story of Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck is unique and touching. Schumann initially moved to Leipzig to study law, but soon found that he wanted to take piano lessons from Friedrich Wieck, probably the most prominent teacher in Leipzig at that time. As was customary, Schumann moved into the house of his piano teacher and really enjoyed his time in the big city, and with the servant girls. At the same time, Wieck was grooming his daughter Clara to become a star pianist, and he controlled every aspect of her life. He not only coached her musically, but also dressed her and even wrote her diary for her. Robert was twenty-five when he fell in love with sixteen-year old Clara. Wieck wanted his daughter to stay well clear of Schumann, and when they got secretly engaged in 1836, he threatened to shoot Robert if Clara should ever mention his name again. He also scheduled Clara’s next musical appearances far away from Leipzig. In the end, the matter went before the courts and after a long period of nasty legal battles and bitter fights, Robert Schumann finally married Clara Wieck on 12 September 1840, the day before her 21st birthday. That’s what I call a classical romance with a happy end; at least initially.

Robert Schumann: Impromptus on a theme by Clara Wieck, Op. 5 (Andor Földes, piano)

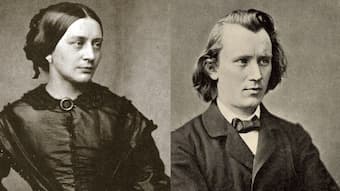

Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann:

Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann

In the history of classical music composers, Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann, and Johannes Brahms are surely the most famous love triangle. Brahms first visited the Schumann’s in 1853, and Robert helped him to get his career started. Robert had been hearing voices in his head for some time, and after attempting to take his own life he was admitted to a mental hospital. Brahms rushed to Clara’s side and was allocated a bedroom on a separate floor in the Schumann house. He was head over heels in love with Clara, but the situation was seriously messy. Schumann was Brahms’ hero, Clara was taking care of seven children, and then there was the age gap. She was 35 and Brahms was 21, and both were raked by feelings of anxiety and guilt. Every tabloid wanted to know if they actually had become lovers, and that question is still debated today. For what it’s worth, I don’t think they ever did because in Brahms’ mind Clara had become a saintly figure that stood well above earthly matter. And we do know that he had the deepest respect for her as an artist and as a woman. Once Robert died in 1856, Brahms and Clara were free to marry, however, Brahms ruthlessly turned her away. Neither of them married anybody else, and they retained an inescapable platonic connection for the rest of their lives. Clara focused on her performances and Brahms became a grumpy old composer.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 15

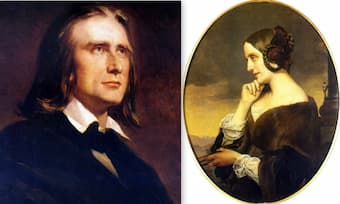

Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult:

Franz Liszt and Marie d’Agoult

When we talk about classical romance among classical music composers the name Franz Liszt automatically receives top billing. The tabloid press absolutely loved him, and reports of his serial conquests made headlines wherever he went. Generally portrayed as a wicked womanizer, Liszt actually seemed to have preferred stable long-term relationships. And one of the most important relationships of his early life brought him together with the Countess Marie Catherine Sophie d’Agoult. She was married to an ancient and crusty war veteran, and she sang in a women’s choir in 1833. The guest of honor was the spectacular pianist Franz Liszt. Marie writes in her memoirs, “I use apparition because I can find no other word to describe the sensation aroused in me by the most extraordinary person I had ever seen. He was tall and extremely thin. His face was pale and his large sea-green eyes shone like a wave when the sunlight catches it. Franz spoke with vivacity and with an originality that awoke a whole world slumbering in me.” Marie had been slumbering for sure, as she described herself as “six inches of snow covering twenty feet of lava.” Since Marie was married, they had to leave Paris and in the second volume of “Years of Pilgrimage,” Franz Liszt musically recalled some of the emotionally fulfilling days of traveling with Marie. The couple had a number of children, and Cosima Liszt, born in December 1837, is part of our next famous classical romance.

Franz Liszt: Années de pèlerinage (Italy), “3 Petrarch Sonnets” (Kazune Shimizu, piano)

Richard Wagner and Cosima Liszt-Bülow:

Richard Wagner and Cosima Liszt-Bülow

Talking about another famous love triangle involving classical music composers. Cosima Liszt had a difficult childhood. She was an illegitimate child and her father a traveling virtuoso. Liszt and the Countess Marie d’Agoult had long separated, and that separation hadn’t been amicable at all. As such, Cosima was first raised by Liszt’s mother, and then placed into the care of Franziska von Bülow. Her son Hans was one of Liszt’s best students and he fell in love with Cosima. Franz Liszt was delighted and the couple married in August 1857. During their honeymoon they visited Richard Wagner in Zürich, as Hans had seduced the teenage Cosima to the strain of Wagner’s Tannhäuser. A social relationship developed quickly, and Hans became one of the most enthusiastic supporters of Wagner’s music. That enthusiasm was strained however, when Wagner—who was still married to Minna—and Cosima became lovers in 1862. In due course, Cosima gave birth to three Wagner children, and she obtained a divorce from Bülow in 1870. Wagner’s wife had since passed away, and thus Richard and Cosima married in August 1870. Cosima was completely devoted to her husband’s artistic cause, and they settled in the small town of Bayreuth. The first Wagner Festival took place in 1873, and Bülow became one of the most enthusiastic supporters of Brahms’ music. The mysterious ways of classical romance make for some very interesting stories.

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser “Overture”

Hector Berlioz and Harriet Smithson:

Hector Berlioz and Harriet Smithson

On rare occasions, an important classical romance is actually translated into music. Such is the case with Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, an autobiographical and self-confessional work. It is a symphonic exposé of his unrequited love for the Irish Actress Harriet Smithson. He first saw her in the role of “Ophilia” in Shakespeare’s Hamlet during the 1827-1828 Season. Berlioz was immediately besotted with Harriet, and his obsession grew into a proper act of stalking. He sent her flowers, wrote her numerous letters and even rented an apartment near hers so he could watch her coming and going. And Harriet predictably avoided him like the plague! Berlioz confessed that he “pined for her, lusted for her, suffered, hankered, thirsted and ached for her, and he dreamt of no one but her.” And Berlioz began writing Harriet into his music as well. Essentially, the Symphony Fantastique of 1830 is about an artist who is madly in love with a woman who does not know he exists. He invited Harriet to the premiere, but she did not show up. It took Harriet almost two years to understand that this symphony, and the sequel Lélio, was all about her. She now contacted Berlioz, and he came for a visit. They finally became lovers and were married in October 1833 at the British Embassy in Paris. Imagination tends to be much easier to handle than reality, and this classical romance turned sour in a real hurry.

Hector Berlioz: Symphony Fantastique, Op. 14

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears:

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears

For a classical romance of more recent times we turn to Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears. Pears had won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London, and through a mutual friend, was introduced to Benjamin. A strong friendship quickly developed, and within weeks of their first meeting Britten composed a song for Pear’s tenor voice and strings. They moved in together shortly thereafter, and by the time they arrived in the New World in 1939, they had become lovers. Their highly affectionate personal and professional relationship lasted for almost forty years, until Britten’s death in 1976. Peter Pears was Britten’s great love, but he was also his great inspiration. As such he featured prominently in many of Britten’s works, including Peter Grimes, Albert Herring, The Turn of the Screw, and the War Requiem. The couple also founded the Aldeburgh Festival in 1948, and established the Britten-Pears Young Artist Programme. Neither Pears nor Britten ever spoke publically about their relationship or sexuality. You can’t really blame them, as homosexuality was illegal in Britain until 1967. Pears summed up the relationship in 1980, “ours was not the story of one man. It was a life of the two of us.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears: Riverside Studios 1964