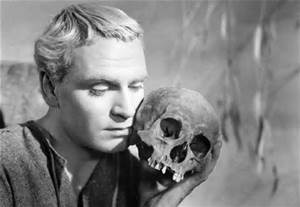

Hamlet

The Tragedy of Hamlet is one of the most quoted works in the English language and has had a pervasive influence on virtually every art form—literature, film, stage, screen, art and music. What better play to perform on a two–year odyssey to every country in the world? Conceived by the Globe Theater of London, the “Globe to Globe” performances began on Shakespeare’s 450th birthday, April 23, 2014, and as of the Madagascar production in January 2016, Hamlet has travelled 267,650 kilometers, to 164 countries.

Who among us are not familiar with the lines? —

“To be or not to be, that is the question.”

“This above all: to thine own self be true.”

“Frailty, thy name is woman!”

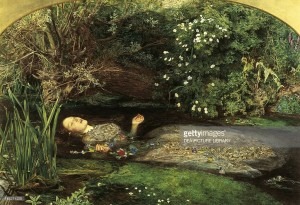

On a frigid night the ghost of King Hamlet declares that his brother Claudius has murdered him. The villain has since seized the throne and has married Queen Gertrude, King Hamlet’s widow. The ghost entreats Prince Hamlet to avenge his death. Feigning madness Hamlet plots to entrap Claudius. Murder and mayhem drive Hamlet’s grief-stricken lover Ophelia to suicide.

Ophelia by John Everett Millais (1829-1896)

Shakespeare fascinated Dmitri Shostakovich and he wrote music for two films about Hamlet. The first, Op. 32a: Suite from Hamlet for small orchestra (1932) is derived from a score he wrote for a theater production in 1932, which was eventually prohibited and censored by Russian authorities.

Shostakovich: Hamlet Suite Op. 116a

Shostakovich’s stunning score for the 1964 Russian film Gamlet, translated by Boris Pasternak, is a classic. The eight-movement Hamlet Suite for orchestra Op. 116a, was complied by Shostakovich’s friend Lev Atovmian. Like Shostakovich’s other works, the music is intense, and the melodies are heartrending. Shostakovich employs his trademark orchestration—a widespread range and unison strings, characteristic of his Symphony 1905 and other works. He combines high, sometimes shrieking woodwinds with low bass sonorities and propulsive rhythms. Sparse pizzicatos (plucking), gives a sense of emptiness and horror and he uses these techniques to provoke terror In The Ghost and The Poisoning movements. A searing lament punctuated by the winds and brass opens and closes the piece. The strident chords in the brass and frenzy in the strings are in stark contrast to Ophelia’s music. Her descent into madness is unnerving played on the harpsichord. Bells and celeste toll her death. Shostakovich masterfully renders the agitation of the play. It’s hair-raising.

Eugène DELACROIX, La Mort d’Ophélie, 1844, Louvre, Paris

Tchaikovsky: Hamlet Overture

Tchaikovsky’s Hamlet Fantasy Overture Op 67 is an orchestral piece in one movement. The work received its premiere in 1888 within one week of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 both of which he conducted. But Hamlet was overshadowed by the Symphony and the overture has never attained the stature of his other works. Of the pieces Tchaikovsky wrote based on Shakespeare, this was the last and most daunting as he attempted not merely to tell the story but to portray the ominous atmosphere and psychological distress of the play. Still it is lyrical and lush.

Liszt: Hamlet Symphonic Poem

Franz Liszt invented the symphonic poem. His Hamlet Symphonic Poem written in 1858 was his tenth in this form. Yet they are rarely performed. In fact, the final version of Hamlet was not performed until 1876 several decades after his death. In the case of tone poems or symphonic poems, the literary source is intended as inspiration for a psychological portrait and not necessarily to recreate the plot. The piece begins with a long slow introduction—eerily, with muted tones in the horn. Liszt indicates “always gloomily” in the sheet music parts and throughout we are assailed by the mood of tension and tragedy. Liszt portrays Hamlet’s turmoil with dissonance. The tone poem ends unresolved.

Brahms: 5 Ophelia Lieder

Glenn Gould and Schwarzkopf perform Ophelia Songs by Richard Strauss

After the death of her father, Hamlet’s rejection and her brother’s obsession with revenge Ophelia has few options. Her heartbreak is the inspiration for musical masterpieces by Brahms and Strauss. Brahms’ Ophelia Lieder, five songs based on Ophelia’s poetry, which probe Ophelia psyche, were written for actress Olga Precheisen for a production of Hamlet in Prague in 1873. The delicate string accompaniment makes the music transparent. Strauss’ Drei Lieder Der Ophelia, Op.67 (Three songs for Ophelia) capture Ophelia’s innocence and charm, yet underlying the dreamy, almost ecstatic music is the brooding descent into madness.

Barbara and Abrahamsen

Ophelia’s predestined fate captivates to this day. This February, in honor of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, the Boston Symphony featured the 2013 song cycle by one of Denmark’s outstanding composers, Hans Abrahamsen, entitled let me tell you for soprano and orchestra performed by Canadian soprano Barbara Hannigan. Based on the novel of the same name by Paul Griffiths, it uses only the 481 words that Ophelia speaks in the play.

I attended a discussion moderated by Harvard music professor Professor Thomas Kelly, with Hannigan, Abrahamsen and the author/librettist Griffiths. The germination of the piece began when Hannigan approached the composer and the Berlin Philharmonic with the idea for an orchestral work centered on the novel let me tell you—even before a note of music had been written—a birthday surprise for Griffiths. Andris Nelsons agreed to conduct the premiere with the Berlin Philharmonic.

The snow scene particularly inspired composer Abrahamsen. “Snow falls. So: I will go into the snow. I will have my hope with me.” Additional excerpts from the text were chosen. Hannigan met with him in Berlin for, “an intense, four hour lecture/demonstration of singing techniques, which included how the voice was used by Monteverdi, baroque composers, by Mahler in his fourth symphony, and I revealed secrets of my own voice.” Transcendent and translucent writing for the voice, the piccolos, and high oboes effortlessly portrays “showers of light.”

The unstable and delicate persona of Ophelia was written from the vantage point of an adolescent. Hannigan asserts that the Ophelia of today, “has poignant wisdom. She has witnessed time, and looks back, in a sense, upon the uncertain role of women over the last 400 years.” A CD was released a few weeks ago. Ophelia’s enigmatic persona continues to enchant.

Very Pleasing to See Your Work