It’s almost uncanny how many musicians follow in their parents’ footsteps and conducting is no exception! Here are three legendary families.

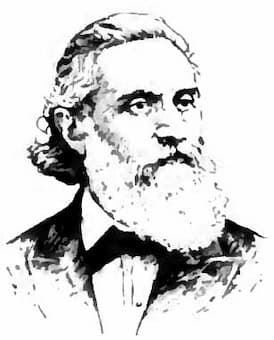

Leopold and Walter Damrosch

Leopold Damrosch © Wikipedia

One of America’s leading and most influential musicians, Walter came from a historically musical family. His father, Leopold, a distinguished composer, conductor, and violinist, was selected by Franz Liszt to be concertmaster of the court orchestra in Weimar, Germany. The family emigrated to the United States in 1871. Leopold became music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1876 and conducted an all-German opera season in 1884-1885 at the Metropolitan Opera, with Walter as his conducting assistant. Then Walter got his big break. When Leopold suddenly became ill, Walter had to step in to conduct Wagner’s massive opera Tannhäuser: his MET debut. It was impressive, so much so that after Leopold’s death, Damrosch was appointed assistant conductor and assistant manager at the Metropolitan Opera. He also took over for his father as the director of the Oratorio Society and New York Symphony Society, the orchestra which in 1928 merged with the New York Philharmonic. Considered the dean of conductors he remained at the helm of the Philharmonic for 41 years.

After a chance meeting with Andrew Carnegie on a steamship to Germany, Damrosch spearheaded the effort to build Carnegie Hall. He commissioned and premiered George Gershwin‘s Piano Concerto in F with Gershwin as soloist, conducted the American premiere of Gershwin’s An American in Paris, and the first performances of Brahms and Tchaikovsky Symphonies, works of Ravel, Wagner, Deems Taylor, Honegger, and Debussy, as well as Rachmaninoff‘s Piano Concerto No. 3 with Rachmaninoff as soloist.

George Gershwin: Piano Concerto in F Major – I. Allegro (André Previn, piano; London Symphony Orchestra; André Previn, cond.)

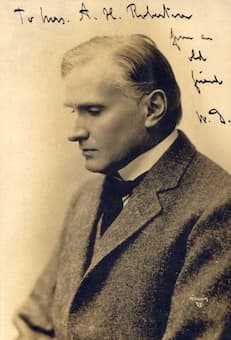

Walter Damrosch

Damrosch firmly believed in the magic of radio that could bring classical music to broader audiences and to the “humblest and remotest dwellings”— difficult to imagine now that music is available 24/7. He led the very first US orchestral concert broadcast and produced a radio series for children from 1928-1942 “Music Appreciation Hour.”

A composer of note, of four operas, he is one of only three American composers who have premiered more than one opera at the MET. (The others are Samuel Barber and Deems Taylor.)

Walter’s older brother Frank was also a conductor, pianist, and educator. He founded the Institute of Musical Art in 1903 which became part of the Juilliard School of Music.

Kurt, Stefan, Thomas and Michael Sanderling

Kurt Sanderling

German conductor, Kurt Sanderling was born in Prussia and studied piano at a young age and by the age of 19, he performed chamber music recitals. His appointment as chief répétiteur of the Berlin State Opera was short-lived. In 1935, during the dominance of the Third Reich, he was stripped of his position and citizenship, and forced to flee to Russia. There he became the chief conductor of the Moscow Radio Orchestra, the orchestra in Kharkov, and finally the Leningrad Philharmonic achieving a reputation as a master interpreter of Shostakovich. They became close personal friends, “For most of his life Shostakovich suffered from the justified fear of being attacked on account of his music.” About the Symphony No. 15 he said, “This first movement is something quite dreadful for me: soullessness composed into music, the emotional emptiness in which people lived under the dictatorship of the time,” and evident in the heart-breaking cello solo in the Adagio movement.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Symphony No. 15 in A Major, Op. 141 – II. Adagio – Largo – Adagio – Largo (Berlin Symphony Orchestra; Kurt Sanderling, cond.)

Thomas Sanderling © Novosibirsk State Philharmonic Society

In 1960, Sanderling was able to return to East Berlin where he conducted the Berlin Symphony Orchestra until 1977 and the Dresden Staatskapelle from 1964–1967.

Sanderling first appeared in Britain with the New Philharmonia in 1972, when conductor Otto Klemperer became ill, chosen because he’d already recorded a cycle of Beethoven symphonies with the orchestra. By 1981 he was recognized as a towering figure in classical music, his considerable reputation growing in the West after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when he began to tour more widely. Engagements with the BBC Symphony, the BBC Philharmonic, the Berlin Philharmonic, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic soon followed. Sanderling continued conducting into his 90s.

Stefan Sanderling © idagio.com

His sons Michael, Stefan, and Thomas continue in his footsteps. Thomas’ distinguished career spans 50 years. Closely associated with the music of Shostakovich and his friendship with the family, (which continues to this day with Irina Shostakovich), Sanderling was presented the original scores to Symphony No. 13 and 14 by Shostakovich. Sanderling has worked with all the major orchestras and opera houses of Europe and Russia, and champions the works of Mieczysław Weinberg. Opernwelt magazine recognized Sanderling’s production of Weinberg’s Der Idiot (after Dostoyevsky’s famous novel), “World Premiere of the Year” in 2013. He recently also won an award for the 2017 recording of the Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich violin concertos with Linus Roth and the London Symphony.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Violin Concerto No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 129 – III. Adagio – Allegro (Linus Roth, violin; London Symphony Orchestra; Thomas Sanderling, cond.)

Michael Sanderling © Marco Borggreve

Michael Sanderling began cello lessons at the age of five and studied with several great cellists including William Pleeth, Yo Yo Ma, Gary Hoffman, and Lynn Harrell. After winning prizes at competitions and appearing as cello soloist and teacher. (I recall a performance with us in Minnesota. Kurt conducted the Brahms Double Concerto with soloists Michael and his wife on violin.) Sanderling made his debut as a conductor with the Kammerorchester Berlin in 2000. He held the position of Principal Conductor of the Dresden Philharmonic from 2011-2019 and has recently been appointed to the position of Chief Conductor of Lucerne Symphony beginning with the 2021/22 season. Michael has been guest conductor of major orchestras in Europe, and he will be making his debuts with several orchestras in the US in 2021.

Erich and Carlos Kleiber

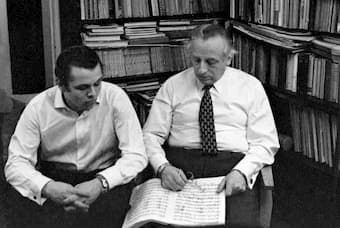

Erich and Carlos Kleiber © History of Music facebook

Regarded as one of the greatest conductors, perhaps of all time, Carlos Kleiber was the son of eminent Austrian conductor Erich Kleiber. Born in Vienna in 1890 Erich was known as an advocate of 20th-century music. He directed the Berlin State Opera and in 1925 conducted the first performance of Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck. Nonetheless his love for Mozart, Beethoven, and Strauss never wavered. He was a scrupulous musician. In protest against the fascist Nazi regime, he left Germany with his family and emigrated to Buenos Aires Argentina in 1935. Erich briefly became the chief conductor of the Berlin State Opera in 1954 but he remained primarily a freelance conductor.

Carlos Kleiber © Andrew Clark

Carlos was raised in Argentina and exhibited his talent at a very early age. He composed and sang, and played piano and timpani, but Erich discouraged a musical career. Carlos attempted to study chemistry in Zurich but music, his first love, called him. He became répétiteur at the Gärtnerplatz Theater in Munich in 1952, was Kapellmeister in Düsseldorf and Opera Zurich, and then in Stuttgart in 1973. These were his last formal posts.

Erich Kleiber © geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at

An enigmatic personality, Carlos appeared rarely, picking and choosing his appearances. His debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1988 electrified audiences. After the resignation of Herbert von Karajan in 1989, he declined the offer to become the music director of the Berlin Philharmonic, preferring to remain incognito, shunning the glamor and publicity usually accorded to maestros. According to the Guardian, his genius was such that, “he knew the entire orchestral and operatic repertoire but only had a tiny selection of pieces he ever played in public; he was one of the funniest, most communicative musicians who ever lived, but never gave an interview…”

His few recordings were considered extremely distinguished, inspired, and spontaneous, he was painstakingly prepared, and his singular conducting style can be seen on several videos including Mesmerized by Carlos Kleiber.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter