“My Moral Duty Is to Write About the Horrors That Befell Mankind in Our Century”

Mieczysław Weinberg

Mieczysław Weinberg, variously spelled Wajnberg, Vaynberg or Vainberg, encountered almost unbearable obstacles and suffering during his life. As a result he composed music with profound emotional content and ethical awareness. However, this engagement with the world around him in response to World War II and its aftermath also produced inward facing music that probes the themes of love and longing, mortality and the search for meaning. Apparently, he found fulfillment in the act of composing, writing late in life, “I must say that composition cause me ever more problems. But there is one good thing about my character. As long as I am writing, the work interests me. When the piece is finished, it doesn’t exist any more.” Weinberg was on his way to becoming a highly promising concert pianist when German forces brutally put a stop to his professional ambitions. As he fled his Polish homeland leaving his entire family behind, the sense of dreadful uncertainty became the foundation for a number of piano sonatas.

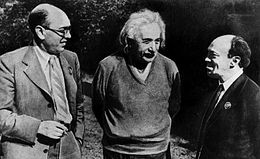

Itzik Feffer, Albert Einstein, and Solomon Mikhoels, year 1943

When Weinberg composed his Piano Trio Op. 24, he did not know what had happened to his family, but he sadly feared the worse. He would, in fact, never see his parents and sister again, as they were murdered in the Warsaw Ghetto. There can be no doubt, however, that the horrors of WWII left their mark on that particular score, but we also sense a surge of optimism and hope. And this sense of hopefulness is connected with his love for Natalia Vovsi-Mikhoels. She was the daughter of the famous Soviet Jewish actor and the artistic director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater, Solomon Mikhoels. He achieved fame as a comedic actor and gifted singer, and a New York Times critic reported “ I saw one of the most stirring performances of my theatre-going career in 1928.” Mikhoels explored more psychological roles in his later career, and in 1939, he was awarded the prestigious “Order of Lenin” and he was named a “People’s Artist of the USSR.” Appointed as chair of the newly formed Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in 1941, Mikhoels traveled the word on behalf of the Soviet war effort, and his family was relocated to Tashkent. Weinberg fell in love with Natalia in Tashkent, and his Op. 24 Piano Trio dating from 1945, is dedicated to her.

Natalia Vovsi-Mikhoels

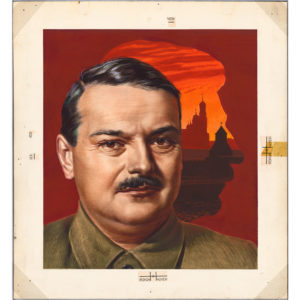

The infamous Zhdanov Doctrine “The only conflict that is possible in Soviet culture is the conflict between good and best,” announced Stalin’s anti-Semitic purges. In charge of ideology, culture and science, Zhdanov began a campaign of extinguishing works exhibiting traits of cosmopolitanism and formalism, “and in particular anything produced by Jewish artists and thinkers.” On the very day that Zhdanov made his announcements on behalf “of compositions that glorify the achievements of the Soviet Union,” Solomon Mikhoels was murdered by the state secret police. His corpse was run over by a truck and his death described as “an accident.” Predictably, his murder was blamed on the CIA. Weinberg himself was arrested on trumped-up charges in January 1953. In truth, his arrest was probably the result of his connection to Miron Vovsi, a close relative of his wife. Miron was the principal defendant in Stalin’s “Doctor’s Plot,” an anti-Semitic campaign accusing Jewish doctors from Moscow of conspiring to assassinate Soviet leaders. It was assumed that Weinberg’s wife and sister in law would be arrested as a matter of course, but Shostakovich personally wrote to Stalin protesting Weinberg’s and his family’s innocence. When Stalin died on 5 March 1953, Weinberg was released and his reputation rehabilitated.

Andrei Zhdanov

Always pragmatic, Weinberg responded to personal and professional adversity by writing music for film. His score for “The Cranes are Flying” won the Palme d’Or at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival. Some of Weinberg’s most ambitious projects dealing with the late Stalinist years found expression in music for the ballet. The “Golden Key” is a fairy tale retold by Tolstoy, which uses puppet characters in an allegory that sees the weak triumph over the strong. “The White Chrysanthemum” of 1958 is an explicit Cold War document, telling the story of a Japanese girl who was blinded during a US air raid. With help from expert Soviet doctors her eyesight is restored, and she is reunited with the faithful boyfriend of her childhood. And let us not forget that Weinberg developed a gift for writing music for cartoons. His most famous score arrived in the 1970s, with three versions for the Russian adaptation of “Winnie the Pooh.” These theatrical experiences not only allowed Weinberg to deal with displacement, loss and resettlement; it also prepared his path for the operatic endeavors from the 1960s.