Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major, K. 467 (Murray Perahia)

The notion of the “canon” of classical music developed about 200 years ago, when the patronage of composers and music by the aristocracy lost its stranglehold on what kind of music was written and performed, and the tastes and opinions of the general public gained greater currency, in particular the burgeoning middle class, for whom concert-going was an important social ritual. In addition, nineteenth-century music scholarship began to make distinctions between high and low art, what was in good taste and what was not, in addition to a growing sense that music from past eras had a lasting value. This had the effect of elevating certain pieces of music to the status of “better” or “greater” than others, and for which an appreciation was regarded as a sign of good taste, education and status (an attitude which prevails to this day in relation to classical music).

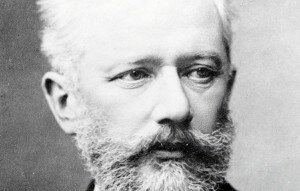

Tchaikovsky

The core canon tends to comprise music which is regarded as “great” and “well-known”, and which is generally recognised by most people. Although the core canon is not set in stone, for the pianist it includes Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (often referred to as The Old Testament), Mozart’s Piano Sonatas, Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas (The New Testament), Schubert’s Impromptus, Chopin’s Etudes and Nocturnes, Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes and Rachmaninoff’s Preludes, as well as the great concertos – Mozart’s No. 21, Beethoven 4 and 5, Schumann, Grieg, Liszt, Tchaikovsky No. 1, Rachmaninoff 2 and 3…. Cynics may regard these works as the over-played warhorses of the repertoire because they appear so frequently in concert programmes – but there’s a good reason why they do: they are very popular and also very fine works.

Frédéric Chopin: Etude No. 1 in C Major, Op. 10, No. 1 (Istvan Szekely, piano)

Peggy Glanville Hicks

Come the twentieth century and the core canon is not so clearly defined. As a pianist and teacher I would not want to be without Debussy’s Preludes, Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, Bartók’s Mikrokosmos, piano sonatas by Prokofiev, Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues, Hindemith’s Ludus Tonalis, Messiaen’s Vingt regards sur l’enfant Jesus, Ligeti’s Etudes and Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes, and Philip Glass’ Etudes.

Peggy Glanville Hicks: Prelude for a Pensive Pupil (Christina Petrowska-Quilico, piano)

Today, shifting cultural consensus and musical taste, a move away from the view that only dead white men wrote great music, and a desire to present greater diversity in concert programmes and teaching curricula have blurred the definition of the core canon. Now music by female, BAME and ‘forgotten’ composers is considered valuable and worthy of inclusion. This has to be a good thing because it demonstrates, and celebrates, the breadth of the repertoire, and offers audiences the opportunity to experience a greater variety of music alongside the well-known and much-loved “greats”.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter