I’ve just seen the funniest cartoon ever! It is based on a kind of parlor game, where you are to imagine being stranded on a desert island with only a single album available for your listening pleasure. In this cartoon, which I believe originated in the New Yorker Magazine, three people are stranded on a desert island with a phonograph and a single album each. A fourth person is floating on a wooden plank and is about ready to join the others. He is holding up his single album, and the caption reads “Please god, not Rachmaninoff again.”

While the cartoon is hilariously funny, it is also factual. When this particular desert question is asked, Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Piano Concerto habitually comes out on top. Funny, yes, but also a little bit sad, don’t you think? Don’t get me wrong, the Rachmaninoff 2 is a fabulous piece, but it’s not the only concerto in the stable.

I suppose the record companies have been primarily feeding us solo concertos for piano or violin, with an occasional sprinkling of concertos for other instruments. To provide a little counterbalance, I’ve been searching for concertos for two or more instruments, and occasional funky instrument combinations, and here are my top 10.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Concerto for Flute, Harp and Orchestra in C major, K. 299

Marie Antoinette playing her harp

While Mozart wrote a concerto for two pianos and the Sinfonia concertante for violin and viola, the most colorful of his multiple-instrument concertos must surely be the Concerto for Flute, Harp and Orchestra, K. 299. It’s unusual because it emerged from unusual circumstances. When his compatriot Marie Antoinette had been securely installed as the Queen of France, Mozart headed straight to Paris. As always, he was looking for a court appointment, but he never even gained an introduction. Instead, he started teaching composition to Marie-Louise-Philippine Bonnières, youngest daughter of the Duke of Guînes. Apparently, Marie-Louise-Philippine was a very capable harpist, and her father an excellent flutist. As such, the Duke commissioned Mozart to compose a concerto that he could perform with his daughter. It is said that the Duke never paid for the commission and that it might never have been performed. Truth be told, Mozart probably didn’t even like the harp. I read somewhere that he thought of it as a “kind of plucked piano.” The result, however, is pure Mozart magic.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Triple Concerto in C major, Op. 56

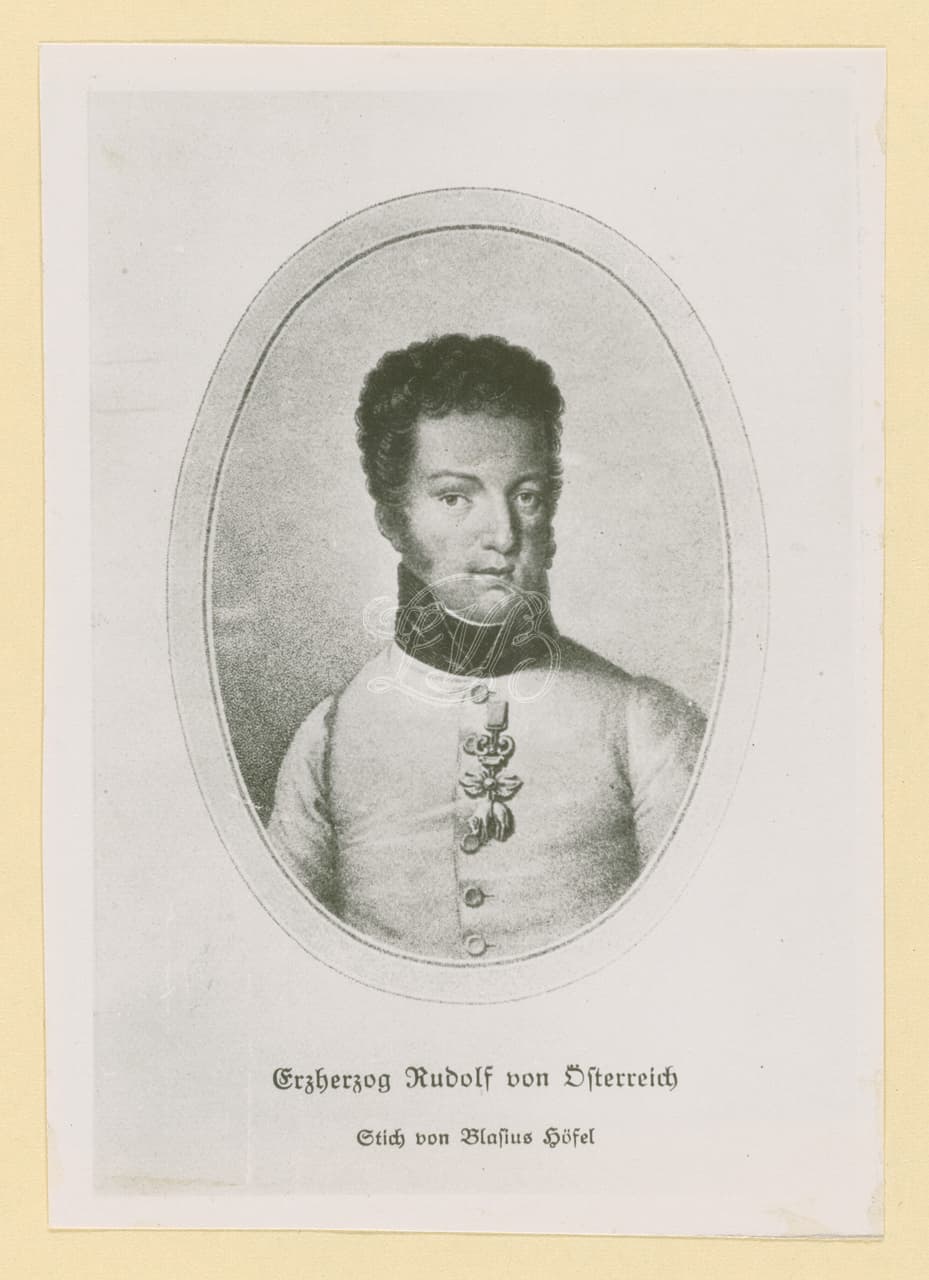

Archduke Rudolf

With Mozart leading the way, Beethoven can’t be very far behind. His “Triple Concerto” is scored for violin, cello, and piano soloists. This seems like a rather strange lineup for a concerto until we realize that the piano part was intended for a sixteen-year-old piano student of Beethoven. And that student was none other than Archduke Rudolf, the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II and Maria Louisa of Spain. Beethoven didn’t really enjoy his teaching duties, and he wrote to a friend, “I have only one pupil and I cannot get rid of him, much as I would like to. I must now give His Imperial Highness Archduke Rudolph a two-hour lesson every day. This takes so much out of me that it makes me almost unfit for any other work.” When Beethoven offered the work to a publisher he described it “as a novelty,” and Breitkopf & Härtel turned him down flat. Since three soloists carry virtually all of the musical argument, it really isn’t a concerto at all, but it is nevertheless highly unusual.

Samuel Barber: Capricorn Concerto, Op. 21

Capricorn in Mount Kisco, New York

Samuel Barber composed his “Capricorn Concerto” in 1944. When I first saw the title, I was sure that it had something to do with astrology. But that is not the case at all. Barber was still serving in the U.S. Army, although his musical talents were well known. In fact, Newsweek called him “the most outstanding American serious composer in uniform.” His fellow officers lobbied the authorities to provide Barber with some extra free time to compose. So, Barber was allowed to go home, which happened to be a house named “Capricorn” on the shores of Croton Lake at Mount Kisco, New York. He had bought the house with his partner Gian Carlo Menotti in 1943 and named it “Capricorn” because it provided maximum sunshine during the winter. The “Capricorn Concerto” is scored for flute, oboe, trumpet, and strings, and designed like a Baroque concerto grosso. Essentially, the concertante solo instruments are in a musical conversation with the string orchestra. For Barber, it was a musical retrospective and he was sharply criticized. “People say I have no style,” he explained, “but that doesn’t matter.”

Samuel Barber: Capricorn Concerto, Op. 21 (Jacob Berg, flute; Peter Bowman, oboe; Susan Slaughter, trumpet; Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

Johann Sebastian Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 2, BWV 1047

Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg-Schwedt

Samuel Barber scored his “Capricorn Concerto” for the very same instruments as Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2. You know the story of how Bach was trying to secure a job with the Margrave of Brandenburg by sending him six instrumental compositions. Essentially, the Brandenburg Concertos are concertos for several instruments. In Bach’s time, the term “Concerto” was rather generic, and it was used to identify work in several movements for a varied combination of instruments.

Basically, you had several soloists and an orchestra arranged around the basso continuo group. The music is passed between this small group of soloists and the full orchestra. That particular instrumental arrangement was actually an Italian invention that rapidly spread across the European continent. In the 18th century, the concerto grosso gave way to the sinfonia concertante, and shortly thereafter, the solo concerto.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 2, BWV 1047 (Henryk Szeryng, violin; Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Neville Marriner, cond.)

However, the concerto grosso made a comeback in the 20th century, as we can hear in the Double Concerto for 2 String Orchestra, Piano and Timpani by Bohuslav Martinů.

Bohuslav Martinů: Double Concerto for 2 String Orchestras, Piano and Timpani, H.271

Bohuslav Martinů: Double Concerto for 2 String Orchestras, Piano and Timpani

Bohuslav Martinů never came to terms with the stifling and conservative musical atmosphere in Prague. And as it happens, Prague did not like him either. As such, Martinů packed his bags and headed for Paris in 1923. Initially, ballet became his favourite medium of experimentation, but by the 1930s, the Czech artistic community in Paris became acutely aware of the worsening political situation in Europe. And this increased political tension was quickly reflected in Martinů’s music. His Double Concerto, written in 1938 but not performed until 1940, gives voice to an intensity of expression rarely heard in his other works. It is patterned after the concerto grosso form, and “a fiercely dynamic opening is inundated with forceful energy and shrieks of war. And the contrasting anguished lyrical section is brutally disturbed by a menacing angularity of the rhythm.” Martinů’s worst fears came true in the end, and he had to flee Paris after the Nazi invasion of the city.

Bohuslav Martinů: Double Concerto for 2 String Orchestras, Piano and Timpani, H.271 (Ivo Kahánek, piano; Essen Philharmonic Orchestra; Tomáš Netopil, cond.)

Max Bruch: Concerto for Clarinet and Viola in E minor, Op. 88

Max Bruch: Double Concerto

Turning next to a gentler combination of instruments, we listen to a concerto for clarinet and viola by the German composer Max Bruch. Bruch was much celebrated for writing his famously rich and seductive violin concerto in G minor. Bruch actually wrote three concertos for the violin, but during the later stages of his career, he wrote an intriguing double concerto for clarinet and viola. That concerto was expressly written for his son Max Felix Bruch, who was a highly gifted clarinetist. In some circles, he was actually compared to the famous Richard Mühlfeld. Premiered shortly before Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps shocked audiences, the Bruch concerto was called “harmless, weak, unexciting, first and foremost too restrained, and its effect unoriginal.” It is scored in three movements and the expressive qualities of the music outshine any sense of virtuosity. Since nobody liked it, the double concerto was only published 22 years after the composer’s death.

Max Bruch: Concerto for Clarinet and Viola in E minor, Op. 88 (Sharon Kam, clarinet; Ori Kam, viola; Sinfonia Varsovia; Gregor Bühl, cond.)

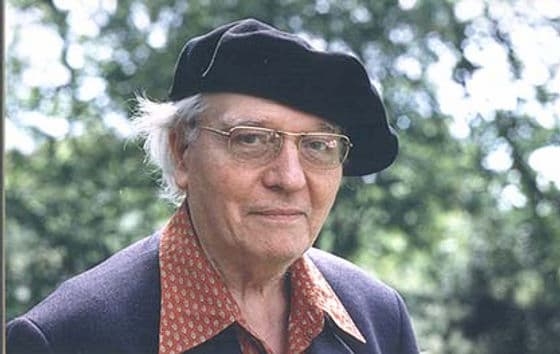

Olivier Messiaen: Concert à quatre

Olivier Messiaen

The concerto for piano, cello, flute, oboe, and orchestra was the final work of the French composer Olivier Messiaen. It started out as an oboe concerto for Heinz Holliger, and progressed to a work for oboe, cello, piano, harp and orchestra on the subject of Grace. Eventually Messiaen dropped the harp, and he outlined a five-movement structure. However, as his health declined rapidly in 1992, the work stands in only four movements. The composer mentions Mozart, Scarlatti, Rameau, and his usual birdsong transcriptions as sources of inspiration. There is plenty of Mozart in the opening movement as it features a theme inspired by Susanna’s aria in Act 2 of Le nozze di Figaro, which is juxtaposed by the songs of a garden warbler and the blue-wattled crow from New Zealand. The second movement is a transcription of his own “Vocalise,’ and the third movement titled “Cadanza” focuses on the four soloists; I guess we could call it dueling birds. When all is said and done, the work concludes on an A Major chord, “a key Messiaen associated with joy.”

Olivier Messiaen: Concert à quatre (Catherine Cantin, flute; Heinz Holliger, oboe; Yvonne Loriod, piano; Mstislav Rostropovich, cello; Bastille Opera Orchestra; Myung-Whun Chung, cond.)

Joaquín Rodrigo: Concierto Andaluz

Joaquín Rodrigo

The Concierto de Aranjuez by Joaquín Rodrigo was a milestone of historical importance. It was the first modern work for solo guitar and orchestra. It was composed in 1939 during Spain’s raging Civil War, and the composer was much concerned with finding the right balance between a solo guitar and a large orchestra. Many years later, in 1967, he was commissioned by the “Los Romeros” guitar quartet to provide a follow up composition, but for four guitar soloists this time. The composer was really worried about repeating himself, and simply creating a new version of the Concierto de Aranjuez, with the solo part simply multiplied by four. So the composer came up with the idea of writing a work inspired by the folk music of Andalusia. He does not actually use direct quotations, but “instead draws on sources for rhythms, turns, and the fundamental spirit of the concerto.” Just have a listen to the exciting “Tempo di bolero” in the first movement, as the strings provide the castanet accompaniment.

Giovanni Bottesini: Gran Duo Concertante

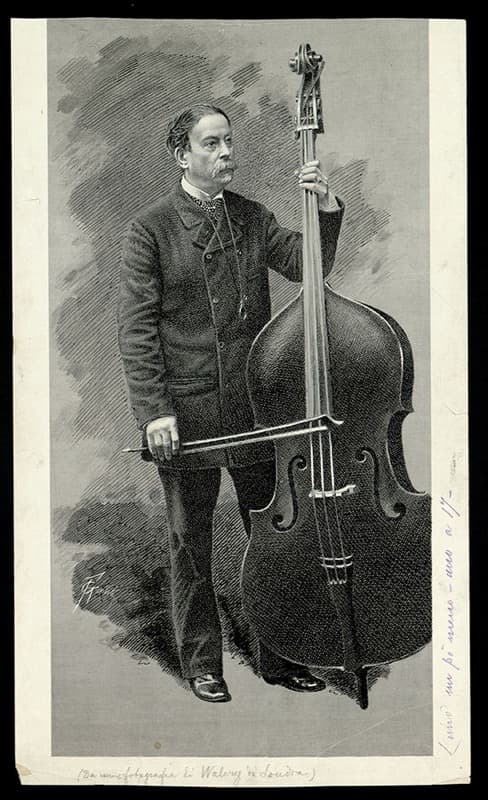

Giovanni Bottesini

From listening to gently strumming Spanish guitars let us now turn to a couple of grumbling double basses. At least that was the original intent when Giovanni Bottesini composed his “Gran Duo Concertante” in 1880. Bottesini and Luigi Negri, another double-bass virtuoso and former classmate, premiered the work. That original version, however, did not last very long as one of the double bass parts was rewritten for the violin and greatly expanded by Camillo Sivori, a staunch disciple of Niccolo Paganini, and at one time touring partner of Bottesini. Sivori was very proud of his contribution, so much so that he claimed the violin part in his own list of compositions. Seemingly Bottesini did not object nor give credit, as he later appeared with such celebrated violinists as Vieuxtemps, Wieniawski, and Papini. A contemporary critic wrote: “It is necessary to hear Bottesini in the piece to discover what possibilities are hidden in the giant of the stringed instruments; to hear what can be done in the way of sonorousness, tone, lightness of expression and grace.” So much for me introducing the grumbling and growling basses.

Ernest Chausson: Concerto for Violin, Piano and String Quartet, Op. 21

Ernest Chausson: Concerto for Violin, Piano and String Quartet, Op. 21

I want to conclude this blog with one of my favorite unusual concertos for violin, piano, and string quartet by Ernest Chausson. It premiered in Brussels on 26 February 1892, with the renowned Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe, the quartet of Isaÿe’s pupil Mathieu Crickboom, and the young Parisian pianist Auguste Pierret. The composer wrote in his diary, “I must believe that my music is made for Belgians above all, for never have I enjoyed such a success… I feel giddy and joyful, such as I have not managed to feel for a long time… It seems to me that I shall work with greater confidence in the future.” The title of “Concerto” is of course, a slippery one, and this work does not adhere to the 19th-century notion of a concerto. However, as has been pointed out, it is “a concerted chamber work in the spirit (if not the manner) of Couperin and Rameau, based on the notion of friendly competition between heterogenous elements, a solo violin, a string quartet, and a piano.” Chausson’s friend Vincent d’Indy would later suggest that his work “leads us…towards the gardens where bloom the charming fancies of a Gabriel Fauré.” This hasn’t been my favorite unusual concerto for very long. In fact, I discovered it while researching this blog. What other jewels are there still to be discovered? Nobody knows, but we surely can find suitable substitutes for the Rach 2 if we ever find ourselves stranded on a desert island.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter