I have always loved chamber music because it resembles a civilized conversation between different points of view. Of course, the conservation can get heated and disagreeable, but there is great respect among all members, and it’s not like any of the shouting matches that we are exposed to on a daily basis.

© medium.com

Personally, sonatas for piano and solo instruments must be among my favourites, and I try not to miss any such concerts. And at the top of the line are sonatas for violin and piano. It’s no surprise that I have heard the violin sonatas by Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms multiple times on stage.

But as this genre was incredibly popular with composers, there are many more works that I have never heard of or didn’t even know existed before I started writing this blog. Maybe the featured sonatas are not forgotten but simply neglected, but I have tried to find some beautiful selections; I hope you enjoy them.

Albert Roussel: Sonata for Violin and Piano in D minor, No. 1, Op. 11

I had no idea that Albert Roussel (1869-1937) composed two violin sonatas. He is an interesting character, to be sure. Growing up an orphan, Roussel had absolutely no interest in music but always wanted to study mathematics. He eventually did receive some instruction in music, but once he passed the entrance examination for the Ecole Navale in 1887, he was ready for a career in the French Navy.

Roussel did sail the ocean blue for some time, and that included a 2-year tour of duty in China. I am not sure what eventually pushed him towards a professional musical career, but he was already 25 when he started his studies with Vincent d’Indy. A heavy French perfume hovers over the cloudy harmonies of the opening of his first Violin Sonata, composed between 1907 and 1908. He did revise the work in 1931, and some of the spicy and rhythmically vigorous musical gestures probably reflect his experiences during WW1. What a gorgeous forgotten violin sonata, full of charm and soaring melodic lines.

Robert Schumann: Sonata for Violin and Piano in D minor, No. 2, Op. 121

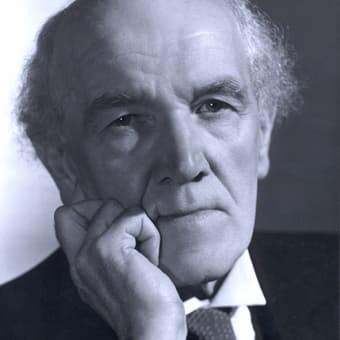

Albert Roussel might not be a household name, but everybody interested in classical music surely knows Robert Schumann (1810-1856). Schuman is famous for his Lieder compositions and his characteristic piano pieces. However, shortly before attempting to commit suicide by jumping into the wintery Rhine River, he turned to a couple of compositions for piano and violin. As he told a close friend, “I did not like the first violin sonata, so I then wrote a second one, which is hopefully better.”

Robert Schumann, 1839

Many works from the last stages of Schumann’s career have been considered products of his deceased mind. And many works from that time have been dismissed, forgotten, or neglected on account of Schumann’s mental health. More recently, scholars have started to look at these compositions as part symptomology and part therapy, and you can still hear great surges and emotional upheaval throughout the composition. With his D-minor violin sonata, Schumann found a temporary cure from his depression, and this four-movement work bursts with vibrant and radiantly positive energy.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Sonata for Violin and Piano in A minor (Charlie Siem, violin; Itamar Golan, piano)

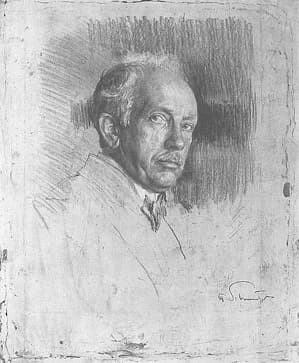

Just like Robert Schumann, Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1985) is not known for his violin sonatas. But just like Schumann, Williams composed such a work towards the end of his life. And just like Schumann, Williams had his critics. He did study with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, but she considered him “the kind of local composer who stands for something great in

the musical development of his own country but whose actual musical contribution cannot bear exportation… His is the music of a gentleman farmer, noble in inspiration but dull.”

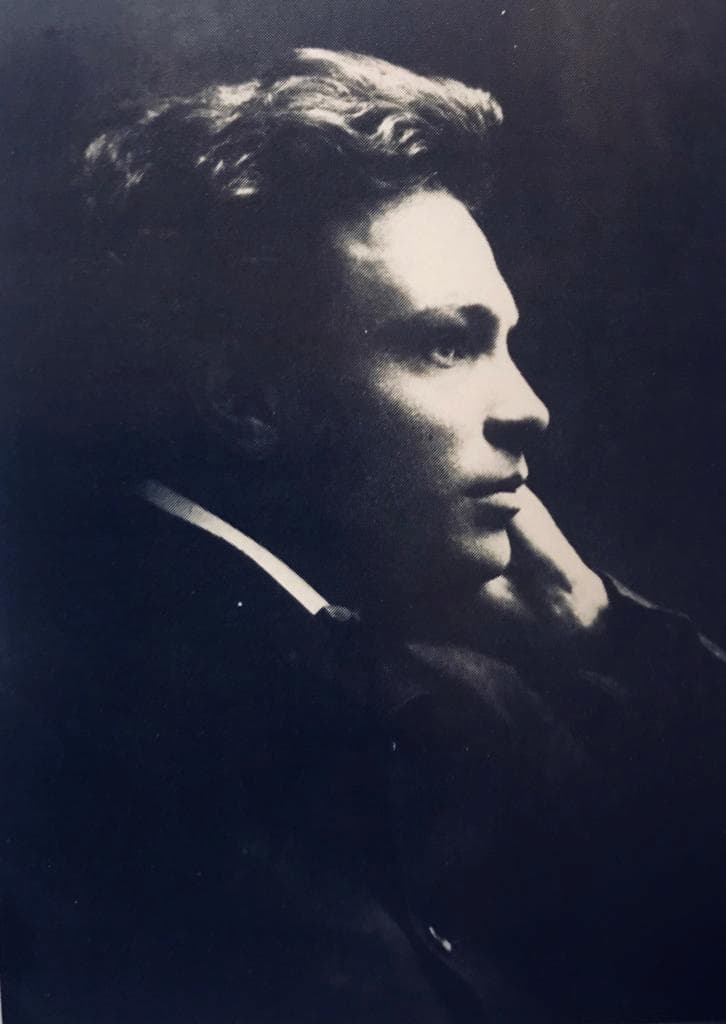

Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1898 © Wikipedia

I am not sure that Vaughn Williams ever knew his teacher’s assessment, but he certainly kept thinking about music, and he steadfastly kept on composing. For Williams, music was the only means of artistic expression natural to everybody. “Music is above all things the art of the common man… it cannot be treated like cigars or wine, as a mere commodity. It has spiritual value as well.” His last chamber work, the Violin Sonata in A minor, first sounded in 1954, and commentators immediately disagreed on its value. Forgotten or neglected, it is a challenging work that seems to communicate a narrative in an orchestrally suggestive way.

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Sonata for Violin and Piano, No. 3

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) must be the single most significant creative composer in 20th-century Brazilian art music. You might have heard the stories of him exploring the unknown geographical and cultural interior of his native country. There is even a story that he was captured by cannibals, but lucky for him and for us, he managed to escape. As he once told a close friend, “My music is natural like a waterfall.”

Villa-Lobos composed three violin sonatas, but unlike Vaughn-William and Schumann, they date from the early stages of his career. Villa-Lobos had been trained in the European Conservatory tradition, and these three works emerged during his maturation as a composer when he started to establish his own personal language. His Violin Sonata No. 3 dates from 1920 and is rather sophisticated in terms of a musical and harmonic perspective. It is clearly steeped in French influences and specifically in Debussy, but it is already “engaging in an intense dialogue with the works of Stravinsky.”

Niels Gade: Sonata for Violin and Piano in B-flat Major, No. 3, Op. 59 (Maria-Elisabeth Lott, violin; Sontraud Speidel, piano)

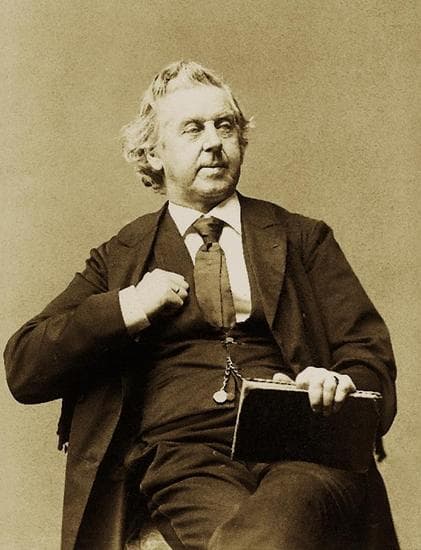

Niels Gade

Niels Gade (1817-1890) was a personal friend of Felix Mendelssohn and of Robert and Clara Schumann. He started his musical career as a violinist in the Danish Royal Orchestra, so it is perhaps not surprising that he composed three violin sonatas. I have to confess that I have never heard of any of these works before, and according to a critic, I shouldn’t bother at all. “They are pleasant enough to hear, yet scarcely significant,” he writes. “The first two sonatas, from Gade’s earlier years, might have been penned by Brahms on an off day.”

I think that Brahms on an off day is still pretty good, but you can easily see how some work might become neglected or forgotten. The third sonata dates from 1885 and presents a four-movement structure opening with a very dynamic allegro. It certainly is interesting as the opening measures in the piano drift away from the home key and the violin enters in F-sharp minor. We also find a playful scherzo and a heartfelt romance, while the composition concludes in a virtuoso manner. This sonata may be forgotten and neglected, but it is certainly worth hearing and must be a lot of fun for the performers as well.

Ottorino Respighi: Violin Sonata in B minor

Ottorino Respighi (1882-1949) is world famous for his “Roman Trilogy” of symphonic poems. Less well known seems to be his B-minor Violin Sonata completed in 1917, just one year after “The Fountains of Rome.” Early in his career, in 1897, the composer had already completed a D-minor Violin Sonata, but in the twenty years since, he was looking to advance the chamber repertoire away from Russian and Germanic influences.

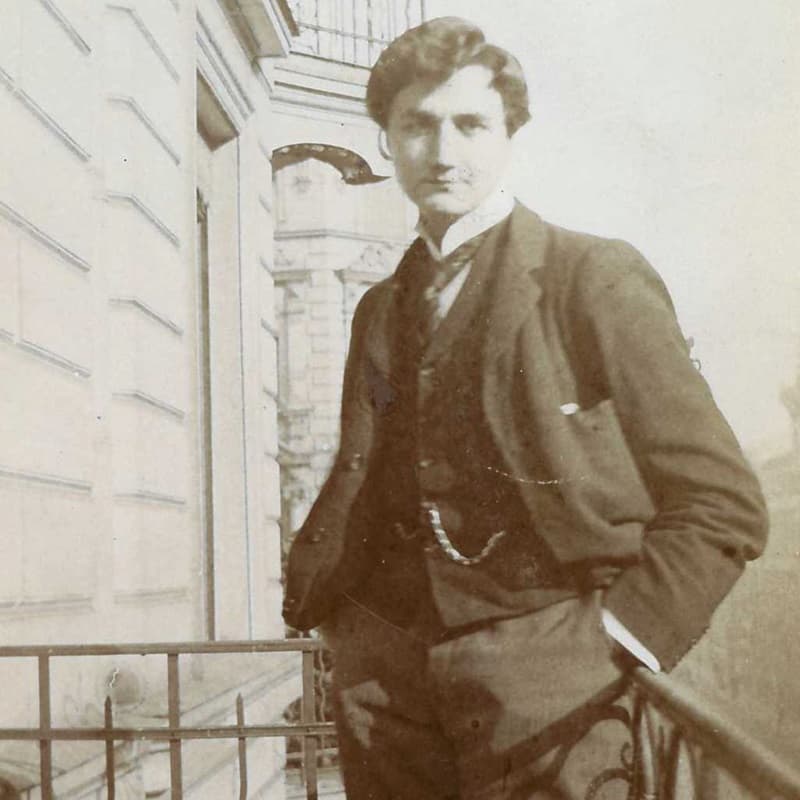

Ottorino Respighi, 1912

Respighi speaks with an Italian voice and tradition and relies on cyclical thematic ideas between the movements and plenty of rhythmic and metrical complexity. There is lots of expressive tension, which sometimes feels almost overpowering. The harmony contributes to this tension, and the musical language is rather complex. The work unfolds in three movements, and you can really hear Respighi’s voice in the “Andante espressivo,” and the concluding “Passacaglia” with its beautifully crafted variations.

Dora Pejačević: Violin Sonata in B-flat minor, Op. 43 “Slavonic” (Raphaëlle Moreau, violin; Célia Oneto Bensaid, piano)

Dora Pejačević (1885–1923) was born in Budapest, but grew up in her ancestral Croatia. Her mother was a Hungarian countess, “a woman of great beauty who was a trained singer, played the piano, and was a fine amateur painter.” Dora was educated by a private English governess, and she was fluent in several languages. She taught herself to play the piano, and her early compositions paved the way for her study abroad. In musical terms, she was largely self-taught, “which is remarkable considering the inventiveness, rich brilliance and enduring quality of her compositions.”

Dora Pejačević

Her ”Slavonic Sonata” does have an Eastern European flavour, while continuing and expanding in a romantic tradition of the violin sonata. She travelled across Europe, and her works were particularly popular in Germany, and the “Slavonic Sonata” showcases an interesting mix of German motivic development and structure with Slavonic-inspired themes and rhythms. It was written during the first world war while Pejačević volunteered as a nurse. For me, this is truly a forgotten and neglected work that should be performed much more frequently.

Ernő Dohnányi: Sonata for Violin and Piano in C-sharp minor, Op. 21 (Key-Thomas Markl, violin; Angelika Merkle, piano)

Ernst von Dohnányi (Ernő Dohnányi) © thepianofiles.com

Ernő Dohnányi (1877-1960) was a gifted composer and an internationally renowned virtuoso pianist. He had studied piano with István Thomán, a favourite student of Franz Liszt, and composition with Hans von Koessler, himself a cousin of Max Reger. Although he was influenced by both Kodály and Bartók, his personal musical style stayed closer to the Romantic idiom and his hero, Johannes Brahms. He composed two wonderful violin concertos, and his most important chamber work for violin and piano is the C-sharp-minor Op. 21. It was composed in Berlin in 1912, and it is a fully mature work.

From the very beginning, I hear a mixture of stylistic traits taken from Brahms and Liszt, and he certainly seems to have closely studied the Brahms Violin Sonatas. There is no actual slow movement in this work, and Dohnányi’s is “concerned to establish thematic unity and interconnection across the three movements by means of variation and thematic reminiscence in order to bind the work into a unity.” Isn’t it a beautiful work? Seems to me that it should be performed much more frequently.

Charles-Marie Widor: Sonata for Violin and Piano, No. 2, Op. 79 (Hans Maile, violin; Horst Göbel, piano)

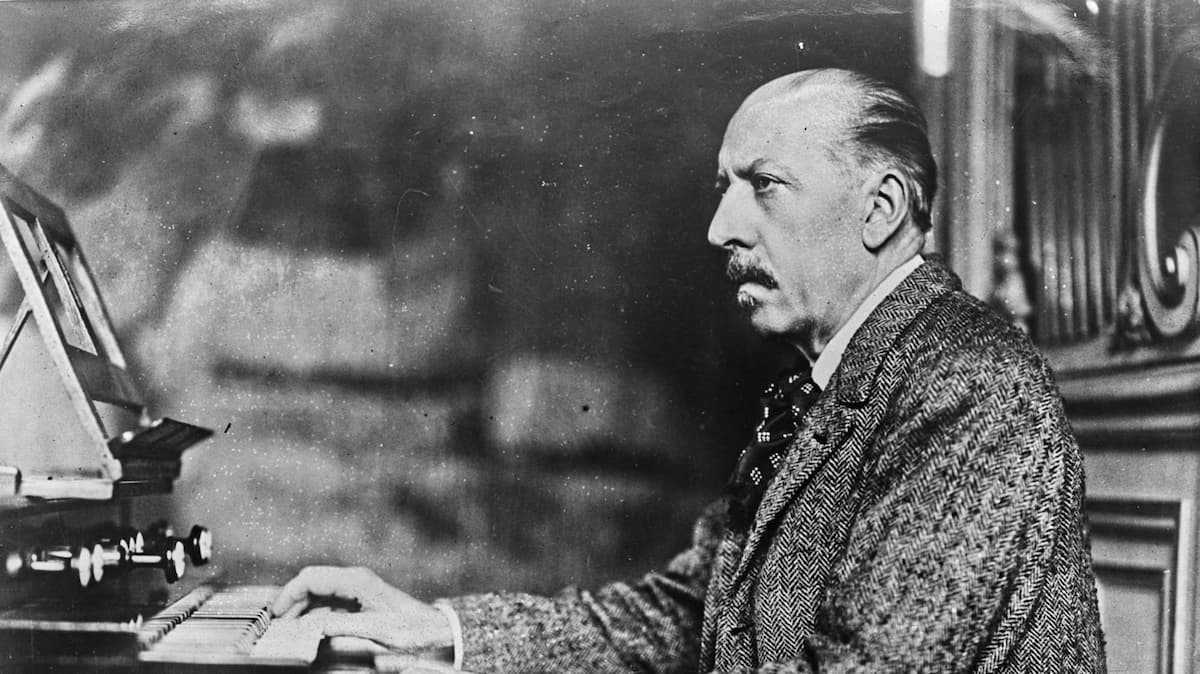

Charles-Marie Widor

Charles-Marie Widor (1844–1937) was a genius organ performer at a very early age. Can you imagine that he successfully competed for a job as an organist in his hometown of Lyons at the age of 11? By age 25, he held the most prominent and most powerful organist position in all of France. And as a composer, Widor is primarily known for his 10 powerful organ symphonies. His name became so closely associated with music for the organ that the rest of his many other compositions, including orchestral and chamber music, stage works, and songs, have been forgotten and neglected. And that includes a Romance, Cavatina, and Suite Florentine for violin and piano, and two Violin Sonatas. His second sonata, Op. 79 first sounded on 14 March 1907, and it is a magnificent work in the best French violin tradition.

Only very recently has the musical world once again taken a keen interest in the works by Nicolai Medtner (1880-1951). He was one of the very last Romantic composer-pianist, but he was overshadowed by his contemporaries Scriabin and Rachmaninoff. His compositions are firmly rooted in the Western classical tradition but frequently tempered with a vigorous Russian spirit. A critic writes, “his musical idiom changed very little throughout his career, and his entire output is remarkably consistent in quality.” And that output includes a few shorter works for violin and piano and three sonatas for violin and piano.

Nicolai Medtner

Medtner tells us that his first Violin Sonata was inspired by the myth of Dionysus, the god of wine and intoxication. In ancient times, that god was worshipped through ecstatic song and dance, and Medtner entitles the three movements of the sonata as “Canzona,” “Danza,” and “Ditirambo,” a kind of choric hymn and dance to Dionysus. Lilting dance rhythms in the first movement are followed by a conversation that turns rowdy in the Presto. The ceremonial “Ditiramo” heralds an approaching procession, and at the height of activity, Medtner brings back fragments from earlier movements. What a marvellous work, specifically when it is performed by Oleg Kagan and Sviatoslav Richter.

I hope you enjoyed this collection of 10 forgotten or neglected violin sonatas, and please let us know in the comments what other violin sonatas might fit this category.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Violin sonatas by Bohuslav Martinu

As from Original 1 of 7 Jascha Heifetz Pupil’s, also Milstein 1st Private “Heifetz” Artist Pupil ~ Elisabeth Matesky

Not keen on the Villa Lobos and I wanted to be …

I wish Vaughan-Williams really did live to be 113 years old, but…