It seems to be a sad, tragic fact of human existence that war will always be with us.

Classical composers have served in, survived, and written about war and peace for generations.

Today we’re looking at fifteen pieces of classical music that explore themes of war and peace, dating from the time of Napoleon to twentieth-century conflicts like World War I and the Vietnam War.

The end of Borodino battle © Wikipedia

Joseph Haydn: Mass In a Time of War (1796)

After the French Revolution of the early 1790s and the ensuing vacuum of French leadership, conflicts between the various European powers flared.

The French and Austrians were especially fierce enemies. In August 1796, Austria was mobilizing for war and preparing for an invasion.

This mass was originally written for his aristocratic employer’s wife on her name day. However, Haydn wrote “Missa in tempore belli” (Mass In a Time of War) on the manuscript score, suggesting it was a wider portrait of the politics of the era and the national mood.

Some people believe that the Mass is an anti-war statement, given the music’s disturbed mood.

Haydn lived to an old age, but his final weeks were turbulent, as he died during the Napoleonic invasion of Vienna in 1809.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Wellington’s Victory (1813)

In 1813, the future Duke of Wellington defeated Joseph Bonaparte (Napoleon’s brother) in battle. Napoleonic power was waning, and Germans and Austrians were thrilled.

Ludwig van Beethoven had an inventor friend named Johann Nepomuk Maelzel. Maelzel had recently invented a mechanical instrument contraption, and he asked Beethoven for a piece of music for it to commemorate the great victory.

Beethoven’s imagination ran wild and he came up with a piece for a hundred musicians. Of course, Maelzel could not create an instrument big enough to accommodate that vision, so Beethoven rewrote the piece for a real orchestra.

The work, now called Wellington’s Victory, was premiered in December 1813 at a benefit concert for wounded Austrian and Bavarian soldiers.

The performance imitated the sounds of war and was extremely loud. One attendee apparently reported that it was “seemingly designed to make the listener as deaf as its composer.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: 1812 Overture (1880)

In 1812, Russians began construction on the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, commemorating their victory over Napoleon.

Fast forward several generations to 1880, when Tchaikovsky was commissioned to write a festival overture to mark the completion of the cathedral.

However, the Cathedral wasn’t finished until 1883, and in the meantime, in 1881, Emperor Alexander II was assassinated, souring the national mood.

As for his part, Tchaikovsky wrote to his friend and patroness Nadezhda von Meck that the overture was “very loud and noisy, but [without] artistic merit, because I wrote it without warmth and without love.”

However, audiences have fallen in love with the work, which juxtaposes an Eastern Orthodox melody, La Marseillaise, and God Save the Tsar.

Richard Strauss: Ein Heldenleben (A Hero’s Life) (1898)

In July 1898, Strauss began work on his massive orchestral tone poem Ein Heldenleben (“A Hero’s Life”).

Who is the eponymous hero? There are contrasting indications. At one point before the premiere Strauss claimed it wasn’t him: “I’m no hero: I’m not made for battle,” he said.

At the same time, there are clear parallels between the musical hero and Strauss himself. For instance, Strauss confirmed that the section entitled “The Hero’s Companion” was modeled after the character of his wife, Pauline. (Also, that section ends with what is obviously a graphic love scene…which begs the question, who is participating in that, if not Richard?)

After said love scene, the hero goes “to battle.” Since we can only guess at the hero’s identity, listeners are left to decide for themselves which battle and which war, and whether it’s meant to be read literally or metaphorically.

Reactions to this battle scene – and indeed, the entire tone poem – were not particularly positive. The Musical Courier wrote, “The climax of everything that is ugly, cacophonous, blatant and erratic, the most perverse music I ever heard in all my life, is reached in the chapter ‘The Hero’s Battlefield’. The man who wrote this outrageously hideous noise, no longer deserving of the word music, is either a lunatic, or he is rapidly approaching idiocy.”

Lili Boulanger: Pour les funerailles d’un soldat (1912)

French composer Lili Boulanger was the astonishingly talented younger sister of composer and teacher Nadia Boulanger. Lili started attending classes at the Paris Conservatoire with Nadia when she was only four years old.

At the age of nineteen, Lili began working on Pour les funerailles d’un soldat (“For the Funeral of a Soldier”), written for baritone, choir, and orchestra. She finished it within a few months, in early 1913. Less than two years later, Europe would be engulfed by World War I, making her 1912 work eerily prescient.

The words she sets come from the play La Coupe et les Lèvres by Alfred de Musset. They include the heartbreaking lines, “He died as a soldier, on Christian land. / The soul belongs to God; the army will have the body.”

Maurice Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-17)

On the surface, Maurice Ravel’s pastoral collection of Baroque-style piano works, Le Tombeau de Couperin (“The Grave of Couperin”) seem to have no connection to war or wartime.

However, he wrote them as a response to the violence and trauma of World War I, and each movement is dedicated to a friend who died in the war.

Maurice Ravel as a soldier, 1916

For instance, the opening Prelude bears a dedication to Jacques Charlot, who was a cousin and godson of Ravel’s publisher. Charlot had also transcribed Ravel’s suite Ma mère l’oye for solo piano from its original form as a piano duet.

Some people supposedly got upset with Ravel for writing light-hearted pieces to memorialize his friends. He responded by saying, “The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.”

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Dona Nobis Pacem (1936)

In 1936, justified fears were growing surrounding the possibility of a second world war.

Composer Ralph Vaughan Williams responded to the looming threat by composing a cantata for soprano, baritone, chorus, and orchestra. He called it Dona Nobis Pacem: “Give us peace.”

He chose to set a variety of texts to make his point, including the Agnus Dei from the Catholic tradition, three poems by Walt Whitman, a speech by Quaker politician John Bright, and excerpts from the Biblical book of Jeremiah.

Throughout the work, the phrase “Dona nobis pacem” can be heard.

Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7 (1939-41)

Shostakovich was a composer who, for better and for worse, was never able to escape politics.

It is unknown exactly when Shostakovich began writing this symphony, but he worked on the first movement in the early part of the war. A theme from this movement is often referred to as the “invasion theme.”

On 2 September 1941, as the Nazis bombarded Leningrad, Shostakovich began work on the second movement of the symphony, in between trips to bomb shelters.

The fire of anti-aircraft guns deployed in the neighborhood of St. Isaac’s cathedral during the defense of Leningrad in 1941 © Wikipedia

When he completed it, he made an announcement on the radio:

An hour ago, I finished the score of two movements of a large symphonic composition. If I succeed in carrying it off, if I manage to complete the third and fourth movements, then perhaps I’ll be able to call it my Seventh Symphony. Why am I telling you this? So that the radio listeners who are listening to me now will know that life in our city is proceeding normally.

However, Shostakovich was viewed as too valuable to lose, and he was evacuated from Leningrad in October. He finished the symphony that autumn.

Various premieres were held around the world, including by the NBC Radio Symphony Orchestra, which broadcast its performance of the seventh symphony all across America in July 1942.

However, the most moving performance was doubtless the one that happened in Leningrad on 9 August 1942, when starved musicians came together during the deadly siege to perform the work. Their performance was broadcast on speakers to demoralize the Nazis.

The siege only ended in January 1944. It led to the deaths of 1.5 million people.

Sergei Prokofiev: War and Peace Symphonic Suite (1944)

As a response to the German invasion of the Soviet Union, composer Sergei Prokofiev decided to take inspiration from one of the most beloved Russian novels of all time, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and write an opera based on it. It had the potential to be the composer’s great masterwork.

Unfortunately, the vast scale of the novel, combined with demanding Soviet bureaucracy determined to meddle in major artistic projects, slowed down progress. All thirteen scenes were only performed after the composer’s death.

In 1988, to make the music from the opera more accessible to orchestral audiences, Christopher Palmer arranged themes from the opera into a symphonic suite.

Arthur Honegger: Symphony No. 3 (1945-46)

Arthur Honegger was a Swiss composer who is remembered for being a member of the informal group of Paris-based composers known as “Les Six” that came to prominence in the 1920s. Given his background, his ties to French music weren’t as strong as the others’.

However, he was living in Paris in the summer of 1940 when the Nazis invaded, forcing him to choose which country he wanted to pledge his loyalty to. He chose France. He quietly supported the French resistance, and even composed a Chant de Libération to have on hand for when the Nazis were finally driven out.

His third symphony, written between 1945 and 1946, is an attempt to come to terms with the last half-decade of death and destruction.

Each movement has a heading corresponding to a particular phrase from the Catholic liturgy: “Dies irae” (“Day of wrath”), “De profundis clamavi” (“From the depths I have cried”), and “Dona nobis pacem” (“Grant us peace”).

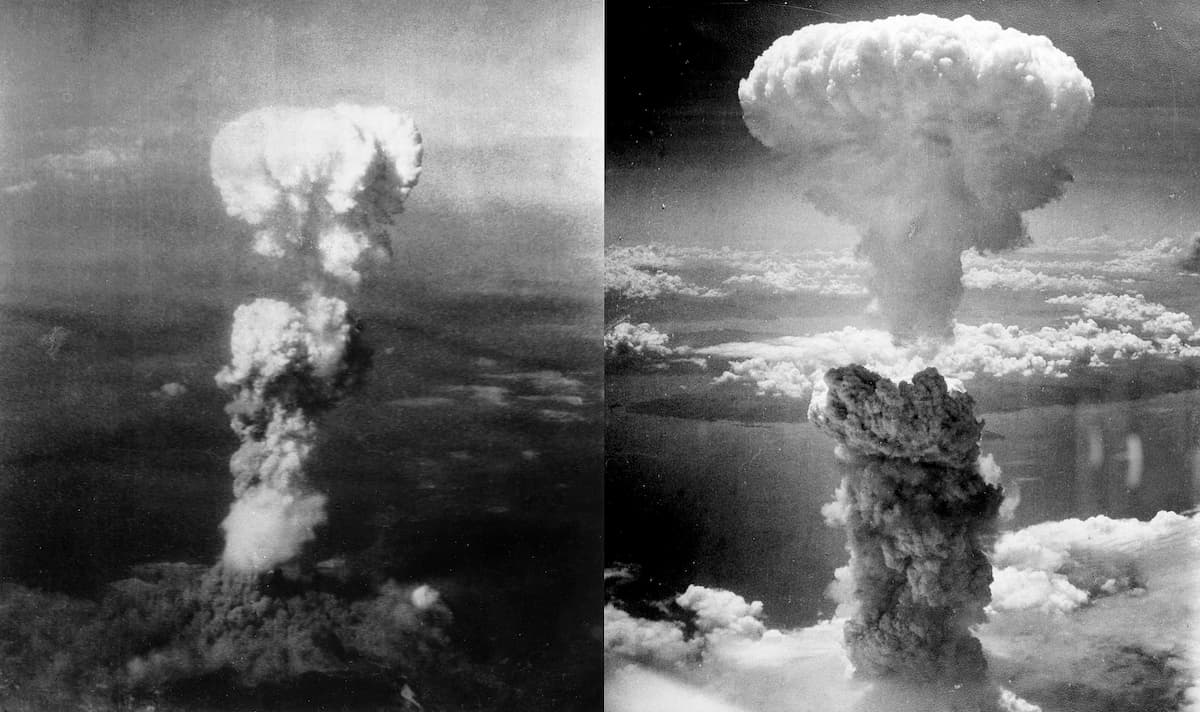

Krzysztof Penderecki: Threnody to the victims of Hiroshima (1960)

This shocking, violent, cacophonous work is written for 52 string instruments. It is a portrait of the horror and destruction wrought by the United States when it unleashed an atomic weapon in 1945 on the Japanese city of Hiroshima in a bid to shorten World War II.

Atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima (left) and Nagasaki (right) © Wikipedia

Interestingly, that association was only made after its composition. Penderecki wrote that once he heard it, he “was struck by the emotional charge of the work… I searched for associations and, in the end, I decided to dedicate it to the Hiroshima victims.”

In 1961, the year after its composition, the work won the Tribune Internationale des Compositeurs UNESCO prize.

Benjamin Britten: War Requiem (1961-62)

Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem was commissioned to observe the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral in Coventry, England.

In November 1940, over five hundred Nazi bombers bombed the industrial city of Coventry. The city’s cathedral, built in the 1300s, was almost entirely destroyed.

By 1956, the city was ready to rebuild. Queen Elizabeth II laid the foundation stone in March 1956. In the spring of 1962, the new building was ready to be consecrated.

For the commission, Britten set the Latin Mass of the Dead. In between, he included poetry by English poet Wilfred Owen, who died in World War I at the age of 25, a mere week before the war’s end.

George Crumb: Black Angels (1970)

George Crumb wrote Black Angels for electric string instruments (“intended to produce a highly surrealistic effect,” the composer wrote), crystal glasses, and suspended tam-tam gongs in 1970.

It was meant to serve as a commentary on the American war in Vietnam, which had reached a horrifying stalemate by the 1970s.

Andrzej Panufnik: A Procession for Peace (1982-83)

Panufnik himself wrote a program note for his Procession for Peace:

This work is a kind of symphonic prelude, written on two planes: the wind instruments and strings play a hymn-like chorale in the metre of 3/4, while the beat of the drums and the timpani reflect the character of a very slow, solemn march in the metre of 2/4.

As this composition was designed for an open-air concert, I was imagining myself as a painter, using a large brush on a huge canvas. After the initial timpani roll, the muted brass with drums starts extremely softly, like a very slowly approaching procession heard from a great distance. Then the brass gives way to woodwinds, and the woodwinds to strings. This invocation gradually becomes more and more intense, and louder, as the procession draws nearer – until the last bars, where the whole orchestra together express with their utmost power an impassioned call for Peace.

Kevin Puts: Silent Night (2011)

Composer Kevin Puts’s opera Silent Night tells the poignant real-life story of the 1914 Christmas truce.

In December 1914, soldiers from both sides emerged from their trenches and began to talk to one another in no-man’s-land. They sang carols, swapped prisoners, and even played games of football together.

Kevin Puts’s opera portrays the experiences of a handful of soldiers from France, Scotland, and Germany, and the difficulty of the juxtaposition between the friendly truce and the unspeakable acts of violence they are ordered to commit.

In real life, the Christmas truces didn’t happen in any kind of widespread way the following years; the brutal bloodshed of 1915 made it impossible.

Conclusion

War will always have an element of senselessness to it, but classical music about war and peace can help us understand the experience of it and pay tribute to all of the men and women who endured it.

Let us know what classical music about war and peace means the most to you.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter