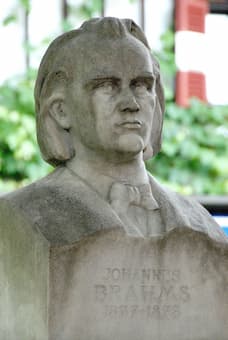

Portrait of Mozart by Saskatoon artist Denyse Klette © DENYSE KLETTE /Saskatoon Symphony

In the endless universe of classical music it is not surprising to frequently find titles of musical works that use the suffix of Latin origin “-ana.” Various spellings none withstanding, it generally indicates a specific tribute of one composer to another composer or a noted performer. For example, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) completed his Fourth Orchestral Suite subtitled “Mozartiana” in the summer 1887, while on holiday in the Caucasus with his brothers Modest and Anatoly.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

This, his opus 61 does not feature original musical materials as the composer explained in a note at the head of the score. “A large number of Mozart’s most admirable small works are, incomprehensibly, very little known not only to the public, but even to the majority of musicians. The author of this Suite, Mozartiana, wished to give a new impulse to the performance of those little masterpieces, whose succinct form contains some incomparable beauties.” The first two movements are orchestral transcriptions of Mozart piano pieces, and the third is a free arrangement of Liszt’s transcription of the “Ave Verum Corpus.” The concluding set of variations is loosely based on Mozart’s piano variations, K. 455 on a theme by Gluck. However, there is a good bit of Tchaikovsky in that movement as well, particularly in the solo violin variation and the impressive clarinet cadenza.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Suite No. 4 in G Major, Op. 61 “Mozartiana” (Swiss Romande Orchestra; Ernest Ansermet, cond.)

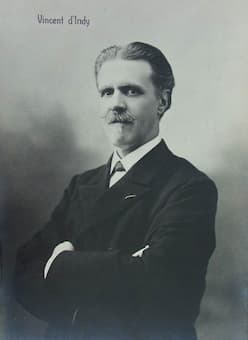

Vincent d’Indy

Vincent d’Indy (1851-1931) was a highly controversial figure accused of being a “narrow-minded pedant of sterilized outdated dogmas.” While music was racing towards 20th century modernism, d’Indy always had his eyes firmly on the past. He publically called Schoenberg “a madman who teaches nothing except that you should write everything that comes into your head… His work is no more than a mass of meaningless notes.” When somebody objected that Schoenberg’s music was to be read, rather than be heard, d’Indy replied, “These noises don’t interest me on paper any more than they do in the atmosphere.” In his youth, d’Indy regularly attended the concerts of the Paris Conservatory and soon realized that his knowledge of the masters of music was inadequate. Therefore, in early June 1873 he made up his mind to travel to Germany, visit the museums he read about, and to hear the “immense masterpieces” of Gluck, Weber, and Beethoven. He also wanted to visit Franz Liszt and Johannes Brahms, whose “German Requiem” he had just studied. Above all, however, he wanted to meet the “great god Richard Wagner,” and to pay respects to him in the city of Bayreuth where a great theatre was presently being built. D’Indy’s wishes were at least partly fulfilled, as he was able to see the first production of Wagner’s Ring in Bayreuth in 1876. While Wagner would become an important inspiration, d’Indy also specifically paid tribute to the revered maestro from Zwickau in his Schumanniana, Op. 30. There are no specific Schumann quotations in this composition; it is simply a delightful adaptation of Schumann’s musical style and thought.

Vincent d’Indy: Schumanniana, Op. 30 (Michael Schäfer, piano)

Frédéric Meinders

The Dutch pianist and composer Frédéric Meinders—born in The Hague in 1946—has been lauded by Marc-André Hamelin as “a uniquely gifted craftsman with boundless imagination.” Meinders started his piano studies at the age of five, and after winning the National Competition for young musicians in the Netherlands, he also won first prize in the Scriabin Competition in Oslo in 1972. As a composer, he has written over 900 original works and transcriptions, about 100 of them for piano left-hand. His transcriptions have been called “among the most ingenious of it’s kind, and entirely worthy of standing alongside those of Liszt, Godowsky and Earl Wild.” For his transcriptions, Meinders frequently looks to his idol Leopold Godowsky by spicing up the harmonies while keeping the style and form in accordance with the original. The musical themes in Schubertiana are by Meinders, but we hear clear echoes of Schubert’s Moments Musicaux and the music for Rosamunde. This Schubert tribute also exists in versions for violin and piano, and for string quartet.

Frédéric Meinders: Schubertiana (Frederic Meinders, piano)

John Salmon

During my brief visiting tenure as musicologist at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, I attended a recital by my colleague, the pianist John Salmon, born in Fort Worth, Texas in 1954. The program that evening, if I remember correctly, was a combination of works by classical masters and works by celebrated contemporary composers of jazz. It mirrored Salmon’s inclination of “always having been a classical and jazz pianist.” The score of Schumann’s Toccata stands side by side with music by Dave Brubeck, Jacques Loussier and Nikolai Kapustin. His Bossa Bachiana was originally scored for women’s chorus and jazz trio, bringing together two musical styles: J.S. Bach’s chorale and bossa nova. Salmon also credits John Lewis’s Modern Jazz Quartet, The Swingle Singers, and Jacques Loussier as musical inspirations for this piece. And we might also mention the French Overture as a formal device.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

John Salmon: Bossa Bachiana (John Salmon, piano)