The Paris Conservatoire opened its doors in 1795, and it was open to students of both sexes. However, theoretical classes like harmony, counterpoint, and fugue, and composition remained exclusively in the domain of men. A scholar writes, “Young women still had to wait until 1903 to compete for the Prix de Rome for musical composition, with Lili Boulanger the first female winner in 1913.”

Paris Conservatoire until 1911

The social expectations for women were very clear at that time, as they were expected to be mothers and housewives only. While women were valued as piano teachers, composition fell under various theories about female inferiority.

As a scholar writes, “The extent to which each composer felt burdened by gender ideology varied considerably, but none of them was indifferent or unaffected, particularly in the reception of their music.”

Lili Boulanger

However, Les Femmes “Compositeurs” did write music, not only in the smaller forms such as songs and piano pieces but also engaged with the “higher forms of chamber and symphonic composition.” The Palazzetto Bru Zane, the “Centre de musique romantique française” has released an impressive anthology of 165 compositions by French Romantic women composers. This sounding survey “will give musicians and music lovers the chance to realize to the full the quantity and variety of this repertory, some of which is still barely known.” So let’s get started with some exceptional orchestral works by Les Femmes “Compositeurs”.

Louise Farrenc: Symphony No. 3 in G minor, Op. 36

Louise Farrenc: Symphony No. 3 in G minor, Op. 36 (Orchestre National de Metz Grand Est; David Reiland, cond.)

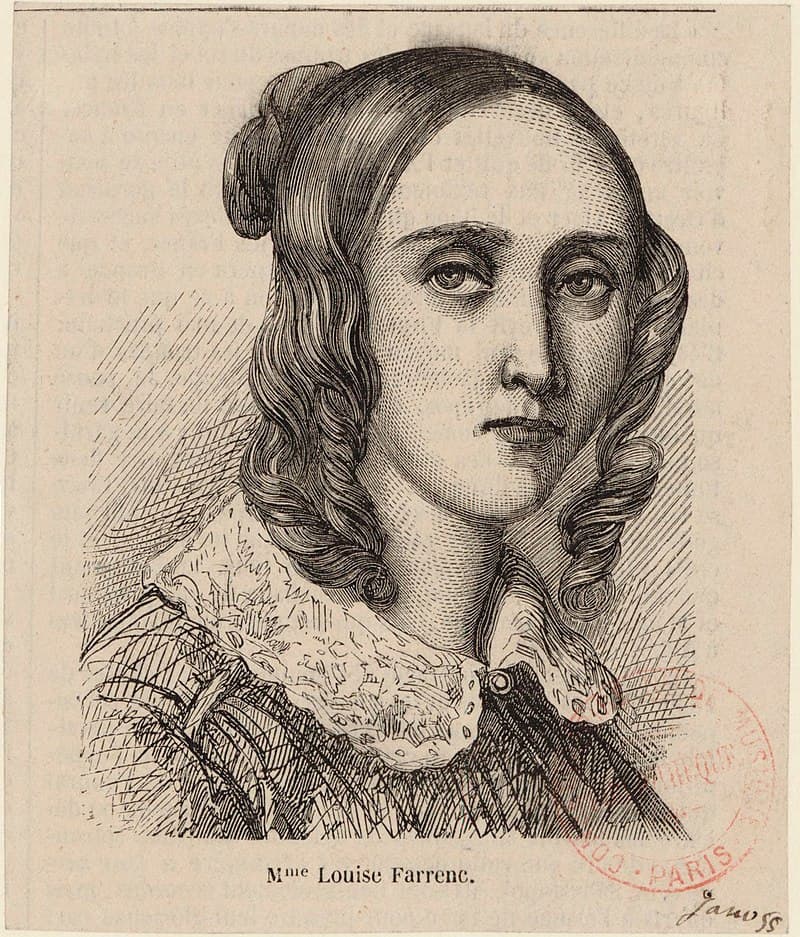

I think that Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) is a perfect example of the 19th-Century divide between social expectations and professional assessment. Robert Schumann wrote, “her works are so sure in outline, so logical in development that one must fall under their charm, especially since a subtle aroma of romanticism hovers over them.” And the musicologist François-Joseph Fétis wrote in 1862, “Farrenc’s mind has the conceptual strength of a consummate master.” A contemporary critic wrote, “Farrenc is in the first rank among composers of music,” and you can see that professionals never mentioned her gender but focused on the quality of her compositions. Farrenc was appointed professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire, but in accordance with social conventions, she was paid much less than her male counterparts. Sadly, that still seems to be the case today.

Louise Farrenc, 1855

Farrenc introduced her 3rd Symphony at a subscription concert in 1849. It turned out to be her greatest triumph as a composer. A scholar and conductor writes “her music reveals a level of inspiration and quality that is without equal in the Paris of the mid-19th century. She has a quite magnificent mastery of musical structures, a full understanding of the subtleties of sonata form as well as a tremendous melodic inventiveness. Thus equipped, she cultivated the art of musical expression with skill and finesse. In the way she juxtaposes strident passages with more poetic ones, she has no equal.” Farrenc presents a substantial first movement in sonata form, a lovely lyrical second movement, a scherzo full of rhythmic intensity, and a dramatic and sizzling concluding symphonic movement. Farrenc skillfully blends a variety of musical styles, ranging from Mozart and Vivaldi to Schubert and Beethoven. She demonstrated once and for all that skillful symphonic composition was not exclusively in the male domain.

Charlotte Sohy: Symphony in C-sharp minor, Op. 10

Charlotte Sohy: Symphony in C-sharp minor, Op. 10 (Orchestre National de France; Debora Waldman, cond.)

To my shame, I must confess that I had never heard about Charlotte Sohy, born Charlotte Marie Louise Durey (1887-1955) before finding this anthology of recordings. It’s astonishing that her works were not published or recorded during her lifetime, but only gradually emerged in 1974! She composed thirty-five opus numbers, including masses, melodies, and pieces for piano, trios, string quartets, as well as a symphony and the lyrical drama “L’Esclave Couronnee.” She also wrote the libretto for her husband’s lyrical drama Bérengère, and wrote several plays and a novel. The highly gifted daughter of an industrialist, she received a thorough education, initially studying music with Georges Marty. A friend of Nadia Boulanger, he attended the Schola Contorum, studying under Alexandre Guilmant and Louis Vierne on the organ, and composition with Vincent d’Indy. During the course of her studies, she met the composer Marcel Labey, whom she married on 12 June 1909.

Charlotte Sohy

The liner notes for the Palazzetto Bru Zane recording write that “this musical couple was exceptional in the history of French music, as husband and wife collaborated and supported each other.” As I already mentioned, Charlotte wrote the libretto for her husband’s lyrical drama, and “Marcel, a conductor, and secretary of the Société Nationale de Musique, programmed his wife’s works during the 1920s and 1930s.” As a sign of the times, however, Charlotte concealed her gender when signing her scores by using the pseudonym “Ch. Sohy,” or “Charles Sohy,” the name of her maternal grandfather. She also composed under the names Louis Rivière or Claude Vincent. Shamefully, her Symphony in C-sharp minor of 1917 was never performed during her lifetime, but “the most striking aspect of her style is a great lyrical and dramatic power.”

Jeanne Danglas: “L’Amour s’éveille”

Jeanne Danglas: “L’Amour s’éveille” (Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth, cond.)

The passionate symphony by Charlotte Sohy was recorded for the first time by the Palazzetto Bru Zane anthology, and the same is true for “L’Amour s’éveille” by Jeanne Danglas (1871-1915). It is shameful that there is hardly any available biographical information on Danglas. We only know that she was the daughter of a locksmith and a seamstress born in Toulouse, and that she spent a short time at the Paris Conservatoire.

Pour la patrie !: marche, composed by Jeanne Danglas

“Her death certificate, drawn up in the tenth arrondissement of Paris on 14 October 1915, describes her as a pianist. And that is all we know of an artist who was barely mentioned in the press at the time.” The publication record shows published mélodies and piano pieces signed ‘J. Danglas,’ with a number of works printed under the name “Jeanne Crabos-Danglas.” As such, “the Bibliothèque Nationale de France indicates these various names as belonging to the pseudonyms of Rosalie Crabos,” who published thirty different pieces including the delightful “L’Amour s’éveille.”

Augusta Holmès: “Andromède”

Augusta Holmès: “Andromède” (Toulouse Capitol National Orchestra; Leo Hussain, cond.)

Of Irish ancestry, Augusta Holmès (1847-1903) was born in Paris. She grew up in Versailles and displayed enormous talents in music, poetry, and painting. And did I mention that at the age of 12, she fluently spoke French, English, German, and Italian. Holmès never attended the Paris Conservatoire, “but took private lessons with Lambert (harmony), Klosé (orchestration) and Sainbris (voice), before becoming a disciple of Franck.” She met the poet, critic, and librettist Catulle Mendès, “with whom she lived for almost 20 years and had five children.” Her initial compositions were written under the pseudonym Hermann Zenta, and Saint-Saëns claimed, “She was France’s Muse.” Holmès favoured musical miniatures, like other female composers of her time, but her admiration for Wagner, whom she visited in 1869, also empowered her to tackle large forms.

Augusta Holmès

A musicologist writes, “Holmès became a champion of various nationalistic causes, emphasizing her Irish roots and French heart in a series of symphonic compositions on nationalist themes.” Her symphonic poems show her fondness for the ancient world, and they musically rely on through-composed Wagnerian procedures. Holmès composed her symphonic poem Andromède in 1883 and published the work in 1902. The heroine is musically presented by broad lyrical phrases and introduced by a lengthy brass fanfare. This exciting work starts in C minor and ends in A-flat Major, with tonality gradually shifting according to the various moods of the music. A contemporary critic wrote, “even if Augusta Holmès has left no great mark on the history of music in general, in the ranks of women musicians she occupies an honoured place.” This seems a rather typical and negative commentary describing les femmes “compositeurs” at the beginning of the 20th century.

Mélanie Bonis: Le Songe de Cléopâtre, Op. 180

Mélanie Bonis: Le Songe de Cléopâtre, Op. 180 (Toulouse Capitol National Orchestra; Leo Hussain, cond.)

Did you know that Mélanie Hélène Bonis (1858-1937) composed about 300 works, including 60 piano compositions, numerous songs, large polyphonic religious works, 30 organ and 11 orchestral pieces, and around 20 chamber music compositions? Unbelievably, she taught herself to play the piano and had to beg for help from César Franck to be admitted to the Paris Conservatoire. Her fellow students included Gabriel Pierné and Claude Debussy, and she had some songs and piano pieces printed by various publishers. Bonis did eventually become the first woman on the committee of the Société des Compositeurs de Musique, but she had previously been confined to a domestic environment. Her marriage to the industrialist Édouard Domange and her duties as a stepmother and mother “kept her away from Parisian musical life.” Although she had gained some public exposure as a composer, the Great War forced her once again into domestic anonymity. “Bonis left a large number of unpublished works that reveal a skilled composer and orchestrator, unjustly neglected in her lifetime.”

Mélanie Bonis, 1908

In 1909, Bonis started work on a collection called “Femmes de légende” containing seven piano pieces named after women whose fates have become legendary. The first piece, “Mélisande” was initially published separately in 1898, and she subsequently added “Phœbé,” “Viviane” and “Salomé.” “Omphale” was published in 1910, and the piano version of “Ophélie” was not published in her lifetime. At the same time, Bonis was working on Le Songe de Cléopâtre, which might well have started out as a piano piece as well. But it had come down to us as a symphonic poem cast in a post-Romantic tradition. It explores the various possibilities of harmony and rhythm, and there seems to be a hint of Impressionism. To conceal her gender Bonis shortened her first name to “Mel,” and later in life she wrote to her daughter, “My great sorrow is that I never get to hear my music.” It’s time to change that, don’t you think?

Marie Jaëll: Ossiane

Marie Jaëll: Ossiane (Anaïs Constans, soprano; Toulouse Capitol National Orchestra; Leo Hussain, cond.)

It really is unbelievable what women composers had to endure. After a partial performance of Ossiane by Marie Jaëll (1846-1925), the critic Victorin Joncières writes in La Liberté on 19 May 1879, “This is the work of a lunatic. It is an accumulation of dissonances, baroque sounds, ceaseless tremolos, and an exasperating use of emphasis, enough to jar the nervous system and send one into fits.”

Marie Jaëll

And another critic writes, “Mme Jaëll would have invented Wagner, had Wagner not invented her.” I suppose critics objected to the growing influence of Wagner in France, and to the fact that Marie Jaëll was a woman. She was born Marie Trautmann in Alsace and took piano lessons from a German piano teacher. She played her first concert when she was twelve and continued her musical studies with Ignaz Moscheles, and then with Henri Herz at the Paris Conservatoire. Jaëll studied composition under César Franck and Camille Saint-Saëns, and she spent some time in Weimar studying with Franz Liszt.

Marie Jaëll had a brilliant career as a soloist, and she gave the first performance of the complete works of Franz Liszt in 1891. And between 1892 and 1894 she performed Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas for French audiences. She also wrote a number of theoretical and pedagogical treatises, and the text for Ossiane, a “Légende symphonique” for soprano, mixed choir, and orchestra. I think she originally wrote the text in German, but it was performed in French. The text “narrates the initiatory ascent of the poetess Ossiane to the usually unattainable summits inhabited by Beles, the god of Harmony.” Not everybody had a negative reaction, however, as Ernest Reyer defended the work, saying “that the composer of Ossiane has an exceptional musical temperament, surprising gifts, and first-class qualities.”

Cécile Chaminade: Callirhoé, Op. 37, Suite No. 1

Cécile Chaminade: Callirhoé, Op. 37, Suite No. 1 (Orchestre National de Metz Grand Est; David Reiland, cond.)

Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944) scored her biggest triumph with a performance of her large scale “ballet symphonique” Callirhoë, produced in Marseilles on 16 March 1888. The work was repeated several times, including in Lyon, Bordeaux, and Cannes. The libretto by the Provençal poet Elzéard Rougier narrates Alcmeon’s love for the slave princess Callirhoé. The suitor is initially rejected, and even the intervention of Venus is fruitless. The heroine is even transformed into a marble statue, but as expected, it all ends well.

Cécile Chaminade

The music was so popular that an orchestral suite was premiered in November 1890. Particularly the third movement became a crowd favorite, but some critics found the music sounded too much like Le Rouet d’Omphale by Saint-Saëns. Despite its popularity, misogynistic prejudices reigned supreme, with a critic writing, “The thoughts have a feminine side in it, a delicious contrast to the writing with a sure masculine hand.”

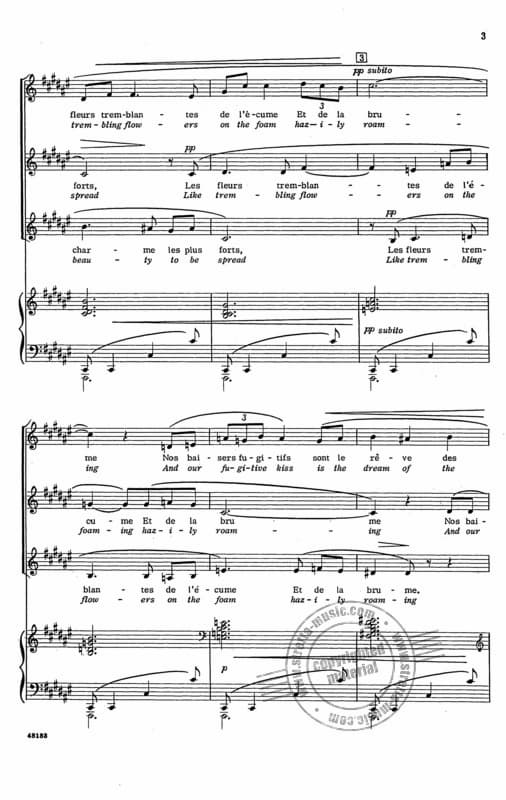

Lili Boulanger: Les sirènes

Let’s conclude this musical survey of orchestral compositions by the Femmes “Compositeurs” with a much more familiar name, Lili Boulanger (1893-1918). She entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1909, and as I previously mentioned, she was the first woman to win the Prix de Rome competition in 1913 for Faust et Hélène. Two years earlier, Lili Boulanger composed Les Sirènes for soprano solo, mixed chorus, and, originally for piano. If the title sounds familiar, it probably should as it shares its title with a movement by Debussy.

Lili Boulanger: Les sirènes

As a scholar has written, “it also has a similar harmonic progression, is in a similar key, and includes wordless vocalization.” The text is by Charles Grandmougin and tells of the mythical sea creatures luring sailors onto the rocks with their irresistible singing. The musical setting has been described as a freshly inspired “water-colour using an impressionist vocabulary.” It certainly is an impressive nature piece, expertly written in what Nadia called “the language of her time.” Please join me next time when I will sample some chamber music compositions by French Romantic Women Composers.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Lili Boulanger: Les sirènes (Anaïs Constans, soprano; Aude Extremo, mezzo-soprano; François Rougier, tenor; Toulouse Capitol National Orchestra; François Rougier, cond.)

I don’t know why Lili Boulanger’s older sister Nadia is routinely not recognized as a composer. It is true that Nadia is more known as a teacher to other composers and that Lili’s success was of more historic significance, but Nadia composed many of her own works and I would have at least given her an honorable mention. But I call this a good article for what it has on these eight composers. Thanks for publishing it.

Mozart’s sister was even a better composer than her Brother, but only her Brother became famous! It’s time for the self called “crown of creation”, to abdicate!

Very interesting article but what about Rita Strohl!?

Thank you so much for this very informative and extensive article! The musical samples top it all up.