Ludwig van Beethoven © Chicago Symphony Orchestra

For Beethoven the pianist, the piano sonata and the piano concerto were his star vehicle of choice. In the piano sonatas, his tremendous virtuosity came to the fore. Remember that when he came to Vienna, he was there as the heir-apparent to the recently deceased Mozart, himself a powerhouse at the piano. But, for the grown-up composer, it can’t be all about himself. You must get an orchestra involved, hence the concertos.

Piano Concertos

Beethoven wrote 5 or 6 or 7 concertos, starting with the Piano Concerto No. 0, WoO 4, of 1784. All that survives of that early work, written when he was just 14, is the piano score, with orchestral cues written into the solo part. Given that beginning, pianist Richard Brautigam reconstructed the work.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto in E-Flat Major, WoO 4 – I. Allegro moderato (Ronald Brautigam, piano; Norrköping Symphony Orchestra; Andrew Parrott, cond.)

It’s Beethoven, but not as we now know him!

His Piano Concerto no. 1 of 1795, on the other hand, is something that is more like the Beethoven we expect. The third movement is less the melody-heavy lines we expect from the heir of Mozart and more of Beethoven’s rhythmic composition.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op. 15 – III. Rondo: Allegro (Maurizio Pollini, piano; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Claudio Abbado, cond.)

© Anghami

Maurizio Pollini’s recordings of the concertos with Claudio Abbado and the Berlin Philharmonic are one of the standout performances of these works. A concerto performance rests equally on the shoulders of the soloist and the orchestra, as led by the conductor, and in these performances, both sides are beautifully handled.

Another of the great recordings of all the concertos is by Stephen Kovacevich and the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Colin Davis. In the other early concerto written in 1795, Concerto No. 2, we have the same movements: a first movement Allegro con brio, a second movement Adagio, and then a third movement Rondo: Allegro. It is in those rolling third movements that Beethoven’s mastery comes out – the piano dances around the orchestra, a fleet-footed performer against the solid backdrop of the orchestra.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 19 – III. Rondo: Allegro molto (Stephen Kovacevich, piano; BBC Symphony Orchestra; Colin Davis, cond.)

Beethoven started his next piano concerto about 5 years later, in 1800. The opening theme is important for the construction of the entire concerto. In the last movement, another Rondo, Beethoven pulls a surprise with only having the piano make the first entrance.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37 – III. Rondo: Allegro (Maurizio Pollini, piano; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Claudio Abbado, cond.)

The fourth piano concerto was finished in 1808. Beethoven was the soloist in the premiere in the infamous 4-hour marathon concert that included Symphonies 4 and 5, the Choral Fantasy, and this concerto. It was Beethoven’s last appearance as a soloist with an orchestra. Again, rhythm comes to the fore in the last movement in this rondo.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 – III. Rondo: Vivace (Friedrich Gulda, piano; Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Hans Müller-Kray, cond.)

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.5 autograph manuscript in facsimile © Old Manuscripts & Incunabula

Concerto No. 5, the Emperor, is the concerto that everyone contends with. The title is not original to Beethoven but was appended to the work by his London publisher. The greatest pianists of each decade have taken up this work: 1920s: Wilhelm Backhaus, Ignatz Friedman; 1930s: Artur Schnabel, Edwin Fisher; 1940s: Joseph Hofmann, Arthur Rubinstein, Walter Giseking; 1950s: Vladimir Horowitz, Wilhelm Kempff, Rudolf Serkin and so on. Paul Lewis’ recordings of the piano concertos with the Jiří Bělohlávek and the BBC Symphony Orchestra give us a solid reading with Lewis’ own ideas.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 73, “Emperor” – I. Allegro (Paul Lewis, piano; BBC Symphony Orchestra; Jiří Bělohlávek, cond.)

Let’s contrast this with Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s direction of the Chamber Orchestra of Europe with Pierre-Laurent Aimard as soloist. The orchestra is lighter and the rhythmic emphasis much stronger.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 73, “Emperor” – I. Allegro (Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano; Chamber Orchestra of Europe; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

After the six concertos numbered 0-5, where’s the last one? In 1806, Beethoven wrote his Violin Concerto in D major, op. 61. In 1807, he took the work that was clearly more pianistic than violinistic and rewrote it for piano as Op. 61a.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto in D Major, Op. 61a – III. Rondo (Daniel Barenboim, piano; English Chamber Orchestra; Daniel Barenboim, cond.)

But in its original form, it does have a wonderful lightness that the keyboard just can’t capture.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 – III. Rondo: Allegro (Joshua Bell, violin; Camerata Salzburg; Roger Norrington, cond.)

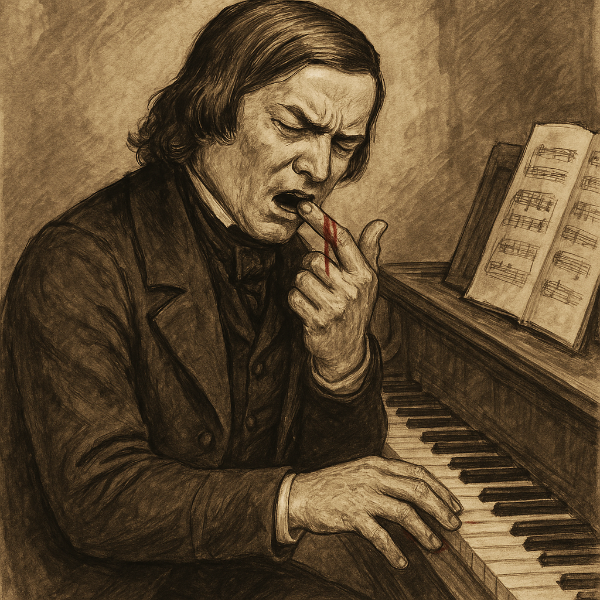

Beethoven conducting inside Theater-An-Der-Wien © California Symphony

Early in his career, Beethoven wrote another violin concerto, but only a fragment remains, an Oboe Concerto of which only a few sketches survive, and in 1808, a Triple Concerto, for violin, cello and piano. Since there isn’t one soloist but three, we could think of this perhaps as a concerto for piano trio. It is thought that this work was written for Beethoven’s pupil, Archduke Rudolf of Austria, mostly because the piano part is suitable for a student whereas the string parts would require more skilled players. However, the Archduke doesn’t seem to have performed the work and, in the end, the concerto was dedicated to someone else.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Concerto for Violin, Cello and Piano in C Major, Op. 56, “Triple Concerto” – I. Allegro (Joseph Kalichstein, piano; Jaime Laredo, violin; Sharon Robinson, cello; English Chamber Orchestra; Alexander Gibson, cond.)

In the concerto, Beethoven made his place on the orchestral stage in a way that complemented his own virtuosity. As each new generation takes up his vision, Beethoven is carried forward through time.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter