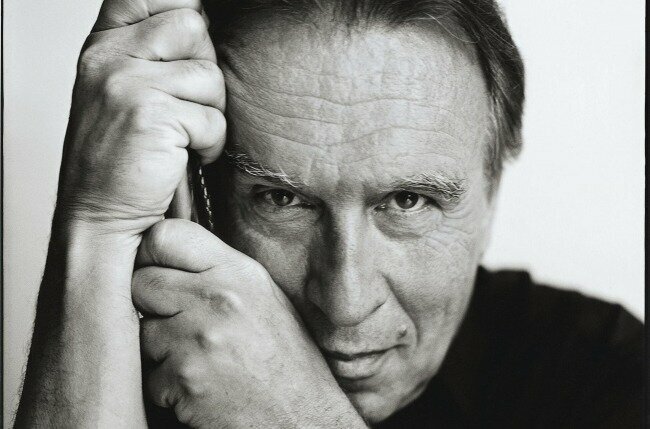

Claudio Abbado

I, on the other hand, never saw him conduct. As a member of a younger generation living in Britain, that’s probably not unusual – in fact, I imagine there are a number of people living in the UK who never saw him, or had to travel to his performances in Lucerne to do so. But his name is nevertheless familiar; it seemed that almost every performance I heard on Radio 3 while I was growing up was preceded or followed by a presenter, usually Rob Cowan, telling us ‘that was the Berlin Philharmonic (or London Symphony or Vienna Philharmonic or Chicago Symphony), conducted by Claudio Abbado’.

As well as the usual fantastic performances, this ubiquity reveals perhaps an underestimated aspect of Abbado’s conducting – his extraordinary range. Abbado began his conducting career in 1960, when the conductors just passed tended to have favoured repertoire and had less cause to go beyond those boundaries. Furtwängler, for example, who died in 1954, centred his repertoire on Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner and Bruckner. Karajan and his contemporaries demonstrated expanded repertoires that included much 20th-century music. But Abbado’s repertoire is striking for its inclusion and championing of a range of genuinely contemporary works, especially those by his Italian contemporaries Luigi Nono, Bruno Maderna, Franco Donatoni and Giacomo Manzoni. At the other end of the timeline, Abbado dedicated some of his last few years of conducting to, unbelievably, a three-disc recording of music by Pergolesi. In between, Abbado was a celebrated interpreter of Mussorgsky, Bartok and Berg as well as his mastery in the German tradition (Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler) and the Italian (Rossini, Verdi). He might well have been the first conductor to perform music from the early Baroque to the present day, and in doing so has set a precedent for today’s conductors; recent programmes, for example, by his successor at the Berlin Philharmonic Sir Simon Rattle include music from Giovanni Gabrieli and Georg Frederic Haas.

Lucerne Festival Orchestra

1978 European Union Youth Orchestra

1982 Filarmonica della Scala

1985 Wien Modern

1986 Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra

2000 Orchestra Mozart

2003 Lucerne Festival Orchestra

While for the early music movement forming ensembles is old hat, this list is striking to me in its different motivations. Groups such as Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s Monteverdi Choir or Sir Roger Norrington’s London Classical Players were founded to create an environment for experimentation and discovery, Abbado’s ensembles were formed by either for young musicians or to create an environment for the highest possible quality of music-making, such as the star-studded Lucerne Festival Orchestra.

Abbado, in his famously understated way, seems to me therefore to have gently redefined the role of the conductor for the following generation. The link between all of his achievements – his wide-ranging repertoire, work with young musicians and creation of new ensembles – is an essential integrity, an ability to take everything and everyone seriously but without doing the same to oneself. He has inspired a generation of musicians, and is an example to us all.

Claudio Abbado in Memoriam (26.06.1933 – 20.01.2014)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter