For “World Pianist Day” 2023, I wrote a little blog featuring some rarely performed or forgotten piano sonatas. As you know, the piano repertoire is absolutely vast, and at the end of my blog, I always invite readers to let me know what other works they would like to see featured. Thank you so much for responding, and because of your wonderful suggestions we have decided to feature a follow-up episode. Here then are 8 more forgotten piano sonatas, getting the fun started with a wonderful work by Algernon Ashton.

Algernon Ashton: Piano Sonata No. 4 in D minor, Op. 164

Algernon Ashton

Algernon Ashton: Piano Sonata No. 4 in D minor, Op. 164 (Daniel Greenwood, piano)

If I have to be completely honest, I was not familiar with Algernon Ashton (1859-1937) at all. Luckily, a reader suggested that we take a look at his piano sonatas, and what a wonderful discovery this turned out to be. Ashton was born in Durham in 1859, but he spent his childhood in Leipzig, Germany. In fact, he studied for four years at the Leipzig Conservatory with Reinecke, Jadasohn and Ernst Richter, and with Joachim Raff in Frankfurt. Ashton returned to England and he was appointed professor of piano at the Royal College of Music in London in 1885.

Ashton was a prolific composer, publishing about 174 opus numbers. We find five symphonies, a piano concerto, a violin concerto, overtures, 24 string quartets in all the major and minor keys, and many songs and choral pieces. Amazingly, he also wrote a total of 24 piano sonatas in all major and minor keys, but only eight were published. The manuscripts of the remaining sonatas were lost when London was bombed during WWII. As a musicologist wrote, “his piano music has little of the Germanic heaviness and is largely without sentimentality. He was not a major innovator but neither a slavish imitator.”

His Piano Sonata No. 4 was published in Berlin in 1925, and we can hear delightful echoes of Schubert and the spirit of Brahms. The music features an impressive range of keyboard colours, and the musical discourse is full of wit and charm, yet thoroughly grounded in a firm command of structure. What a shame that such a delightful work should have been so easily forgotten.

Benjamin Dale: Piano Sonata in D minor

Benjamin Dale

Benjamin Dale: Piano Sonata in D minor (Danny Driver, piano)

Let’s stay in England for a bit and feature another completely unknown, at least to me, composition by Benjamin Dale (1885-1943). Dale had a long association with the Royal Academy of Music. Dale hailed from Islington, London, and he came from an affluent family of enthusiastic amateur musicians. It’s hardly surprising that the young lad got interested in music, and he became an accomplished organist with a small collection of compositions to this name at the age of 14. One year later, he enrolled at the Royal Academy of Music studying composition under Frederick Corder, who was an enthusiastic champion of Richard Wagner and biographer of Franz Liszt.

Dale composed his D-minor Sonata between 1902 and 1905 and it has been described as “the first outstanding British piano sonata. Its harmonic language avoided the clichés of the Beethoven-Brahms style and utilized the resources of Straussian and Wagnerian chromaticism to an unprecedented level.” I also hear influences from Tchaikovsky, Schumann, Balakirev, and Glazunov, but then my ear might just be too easily led.

The sonata was published in 1906 and championed by Mark Hambourg, who even organised a competition to identify outstanding new works. That competition attracted sixty entrants and Dale’s Sonata was declared the winner. There was some kind of disagreement between composer and performer, but the work was also taken up by Benno Moiseiwitsch, Moura Lympany, Myra Hess and Irene Scharrer. So why was this expansive work forgotten? We don’t know for sure, but we do know that Dale travelled to the Bayreuth Festival at the beginning of WWI. He was arrested and interned in a camp near Berlin and only returned to London after the war.

York Bowen: Piano Sonata No. 6 in B-flat minor, Op. 160

York Bowen

York Bowen: Piano Sonata No. 6 in B-flat minor, Op. 160 (Joop Celis, piano)

Camille Saint-Saëns called York Bowen (1884-1961), originally Edwin Yorke Bowen, “the most remarkable of the young British composers.” In fact, Bowen had the reputation as “the finest pianist since Anton Rubinstein.” He was a close friend and classmate of Benjamin Dale at the Royal Academy of Music, and he studied with the esteemed pedagogue Tobias Matthay. He was also an accomplished horn player and violist, but his pianistic skills were utterly remarkable, and his recitals were considered special events.

Bowen also studied composition with Frederick Corder at the RAM, an institution under the spell of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt. A classmate reports that York Bowen and Benjamin Dale “would spend many hours at the opera together, listening to Wagner and so moved that they walked the streets together for hours afterwards.” Yet in his own compositions, which include three symphonies, four piano concertos, a violin concerto, a viola concerto, orchestral suites, chamber music, as well as a large number of piano works, Bowen shows little influence of Liszt or Wagner.

Apparently, he was more responsive to the Russian national school with its pianistic virtuosity, dark atmosphere and epic character. Simultaneously he was interested in French composers and playfully decorated melodies and coloured harmonies with soft dissonances. Bowen’s B-flat minor Sonata was written in 1961, shortly before the composer’s death. I hear a lot of Brahms in the opening movement, specifically of how the rhythmically distinctive main theme evolves throughout the movement. The “Intermezzo” transports us into the English countryside, and Bowen adds a toccata-like Finale. Ah, what forgotten treasures are just waiting to be discovered again?

Ivor Gurney: Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor

Ivor Gurney

Ivor Gurney: Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor (George Rowley, piano)

While Frederick Corder was teaching composition at the RAM, the composition department at the Royal College of Music was in the hands of Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, a decided disciple of Brahms. Among his many students, we find Ivor Gurney (1890-1937), born in Gloucester and rigorously trained by cathedral organist Herbert Brewer. Gurney’s education was interrupted by WWI, and he wrote poetry on the battlefield. In 1917, Gurney was gassed and invalided home, but he eventually returned to the RCM to feverishly compose for a number of years.

Gurney wrote a now-lost symphony, two major orchestral essays, A Gloucestershire Rhapsody (1919–21) and War Elegy (1920), three string quartets, a piano trio, three violin sonatas, fifteen preludes, two sonatas for solo piano and 185 songs. He studied composition with Ralph Vaughan Williams after the war, but Gurney was suffering from bipolar illness, and he was eventually committed to a London mental hospital where he would spend the rest of his life. He did continue to write poetry and music but as his condition advanced, “he musically fell silent in 1926.”

One of Gurney’s most ambitious early works is his three-movement Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor. It dates from 1910 and is dedicated to Margaret Hunt. The expansive opening movement takes a page out of Brahms, Schumann, and Grieg, but also discloses a personal musical originality and confidence. The Largo seems like an extension of Beethovenian processes with a good bit of Schubert mixed in. However, it seems that Gurney is also thinking locally, as Elgar makes a musical appearance in the final movement.

Edward MacDowell: Piano Sonata No. 4, Op. 59 “Keltic”

Edward MacDowell

Edward MacDowell: Piano Sonata No. 4, Op. 59 “Keltic” (James Barbagallo, piano)

This beautiful and forgotten era of British pianism was predictably influenced by composers working in other parts of the world. And that is certainly true of Edward MacDowell (1860-1908). His four rich and complex piano sonatas, just like the work of his British contemporaries, have also been forgotten. Born in New York City, MacDowell took early lessons with Teresa Carreño, one of the greatest woman pianists in the world. Such was his talent that he attended the Paris Conservatoire as a classmate of Claude Debussy, and later on studied with Joachim Raff.

MacDowell played his compositions to Franz Liszt, one of the most influential people in European musical life. He taught piano privately in Frankfurt but returned to the US and received an appointment at Columbia University. His Sonata No. 4 dates from 1901, and it is dedicated to Edvard Grieg. The work also carries the subtitle “Keltic,” and the composer wrote a poetic motto.

Who minds now Keltic tales of yore,

Dark Druid rhymes that thrall;

Deirdre’s song, and wizard lore

Of great Cuchullin’s fall.

As a contemporary wrote, “MacDowell achieved a conclusive demonstration as a creative musician of unquestionable importance. Never before had he given so convincing an earnest of the larger aspect of his genius; the breadth and reach of imagination, the magnetic vitality, the richness and fervour, the conquering poetic charm.” Here you will find a beauty which is as the beauty of the men that take up spears and die for a name, no less than “the beauty of the poets that take up harp and sorrow and the wondering road.”

Georg Tintner: Piano Sonata in F minor

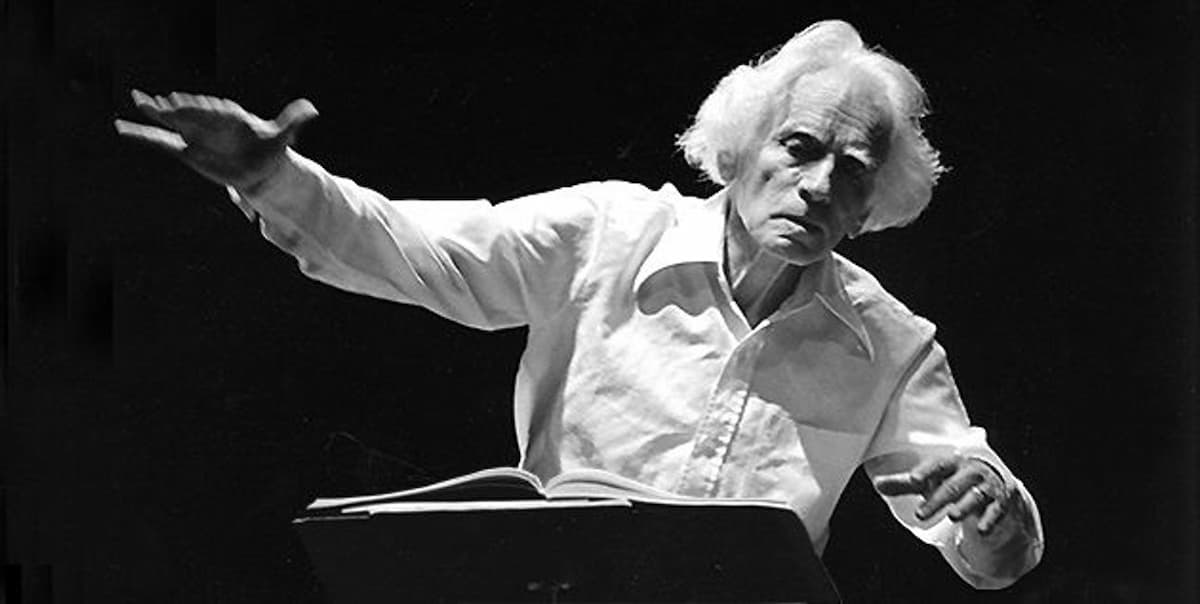

Georg Tintner

Georg Tintner: Piano Sonata in F minor (Helen Huang, piano)

Georg Tintner (1917-1999), born in Vienna, is primarily remembered as a conductor whose career was established in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. He was “the first Jew ever to be accepted “in the Vienna Boys’ Choir,” and he started composing around the age of ten. At the age of fourteen, he entered the Academy of Music as a composition prodigy, studying with Josef Marx, and conducting with Felix Weingartner. Tintner always thought of himself as “a composer who conducted.”

His Piano Sonata in F minor is subtitled “On the Death of a Friend,” and it probably dates from his early years at the Academy. The work unfolds in one movement, and it is full of Romantic gestures and fully tonal. I can hear lots of Scriabin, Chopin, and Brahms, and it is certainly full of the “passions and enthusiasms of youth.” That is hardly surprising, as this remarkably sophisticated work was written by a boy of fourteen or fifteen.

Political atrocities interfered, and Tintner was forced to leave Vienna in 1938. He did spend a bit of time in London before making his way to New Zealand. On route, he was arrested as a German spy in Australia. He led a restless personal and professional life, but Tintner was described as “one of the greatest living Bruckner conductors.” His recording of Bruckner had withstood the test of time, but his wonderful piano sonata has largely been forgotten.

Kurt Roger: Piano Sonata, Op. 43

Kurt Roger: Piano Sonata, Op. 43 (Benjamin Frith, piano)

Kurt Roger (1895-1966) is another name I was not familiar with. Like Tintner, he was born in Vienna and studied with Karl Weigl and Arnold Schoenberg. He clearly was not a follower of Schoenberg, otherwise he would hardly have written a piano sonata. In the event, Roger taught at the Vienna Conservatory but the Nazi Anschluss forced his emigration to the United States via London. He became an American citizen in 1945 and held faculty positions in New York and Washington DC.

Roger’s compositions received notable performances, and his musical style “is a testament to the fascinating and changing musical atmosphere of his life.” Roger shared the Modernist’s fascination with the past, and his works sound a variety of old and new styles using Baroque, Romantic and Modern elements in inventive combinations. His Piano Sonata dates from 1943 and it is a work that clearly does not deserve to be forgotten.

Michael Tippett: Piano Sonata No. 1

Michael Tippett

Michael Tippett: Piano Sonata No. 1 (Peter Donohoe, piano)

Michael Tippett (1905-1998) grew up during a period when English composers were trying to create a distinctively English style. Folk Song Societies published a great wealth of English folk songs, and the sacred music of the Tudor realm was rediscovered. However, revolutionary forces were sweeping Europe by the 1930s, and modern tendencies like expressionism, impressionism and neoclassicism generated new and innovative forms of expression. Tippett, as it turns out, “daringly combined genres and took whatever he needed to express himself.”

A contemporary writes, “Tippett was always his own master. He worked things out for himself and developed and altered his style and remade tradition in a wholly individual way.” I think we might see his Piano Sonata No. 1 as an example of this eclectic approach. The overall form and structure are modelled after Beethoven, but he adds musical influences ranging from Scottish folk song to American jazz, from the English Renaissance to the mysticism of late Beethoven, and from Stravinsky’s rhythmic experiments to Hindemith’s harmonies.

Wow, so many fabulous rarely performed and forgotten piano sonatas. And as I was doing more listening and research, it was clear that I was only scratching the tip of the iceberg. The vast variety and quality of works in this genre are absolutely staggering, so would you please let me know what other piano sonatas you’d like to see featured?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter