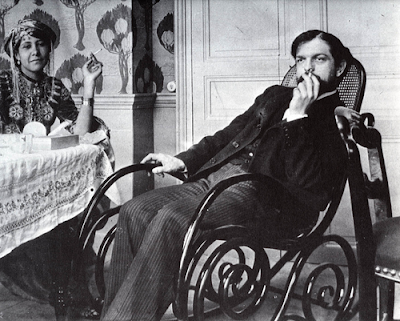

Debussy at the piano! One had to have seen it to appreciate its magic. No words could describe the mysterious enchantment of his playing…

Debussy at the piano! One had to have seen it to appreciate its magic. No words could describe the mysterious enchantment of his playing…

– Jacques-Emile Blanche, 1932

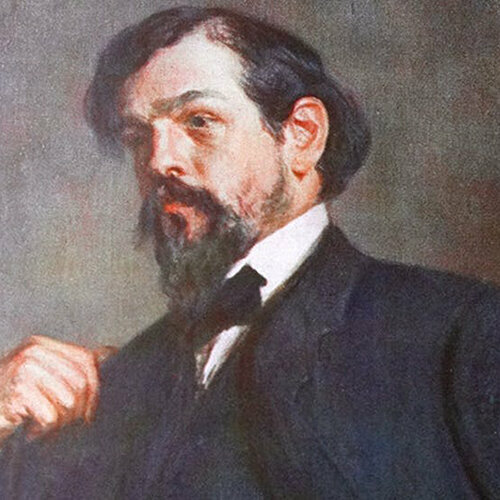

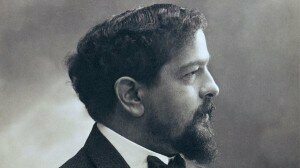

2018 marks the centenary of the death of French composer Achille-Claude Debussy (he died in Paris on 25th March 1918). While rightly noted for his orchestral, chamber music and songs, it is in his piano music that we find the finest examples of his distinctive compositional language. He revolutionised piano music in his use of timbre, unusual tonalities, parallel chords used for colour rather than a strict harmonic progression or structural bridges, the use of whole tone and pentatonic scales, idioms drawn from eastern music. He absorbed many influences, from the music of the Far and Middle East, Russia, Spain and America to that of his Baroque antecedents, the French clavecinistes Rameau and Couperin, yet he created music which was distinctly French and modern, providing inspiration for a diverse range of composers including Ralph Vaughan Williams, Arnold Bax, Charles Tomlinson Griffes, Béla Bartók, Pierre Boulez, Henri Dutilleux, Olivier Messiaen, Ned Rorem, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Toru Takemitsu, George Gershwin, Bill Evans, Thelonious Monk, and Duke Ellington.

Olivier Messiaen: 8 Preludes – No. 6. Cloches d’angoisses et larmes d’adieu (Roger Muraro, piano)

Duke Ellington: Single Petal of a Rose (Luigi Palombi, piano)

He is all too frequently described as an “impressionistic” composer, a term he is said to have disliked, but his attempts to create musical effects certainly bring to mind a visual scene, or ‘impression’, and his music’s lack of fully-realized ideas, dissonant chords and occasionally a seemingly almost complete lack of structure certainly gives listeners the feeling that they are not just listening to a piece of music but to a soundscape.

The Preludes for Piano, in two books, became – and remain – his most popular music for piano, arguably his finest works for the instrument in their variety – from exuberance to bleakness (Feux d’Artifice, Des pas sur la neige), eccentricity and mischief (Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq., La Danse de Puck), languor and drama (La Fille aux cheveux de lin, La Cathedrale Engloutie) – and replete with daring perfumed harmonies, sparkling figurations, and atmospheric textural layers. To encourage listeners, and performers, to respond intuitively to these beautiful piano miniatures, their titles were placed at the end of each piece so that listeners would not call to mind stereotyped images as they listened.

Claude Debussy: Preludes Book 1 – No. 10. La cathedrale engloutie (Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano)

I’m not sure how old I was when I first heard Debussy’s music – the work in question was almost certainly La Mer, which my parents had on LP, and I remember hearing at the Proms when I was a little girl. When I became reasonably proficient at the piano, his Preludes caught my imagination, captivated me with their curious colourful harmonies, sensuous fragmentary melodies and dramatic intensity in miniature form. I learnt La Cathedrale Engloutie when I was about 12 or 13. It was too advanced for me, and my small hands couldn’t really cope with the large chords and octaves, but the work remained a favourite, along with perhaps his best-loved Prelude, La fille aux cheveux de lin. As an adult, returning to the piano after an absence of nearly 20 years, I veered towards the more “grown up” works in Debussy’s oeuvre – Hommage à Rameau, Voiles, the Images Inédites (the forerunner to his better known Images) and the erotically-charged La Plus que Lente. And from Debussy came my interest in the piano music of Olivier Messiaen.

I adore his piano music and I’ve been fortunate to hear some incredibly fine performances of it in concert in recent years – most memorably by Pavel Kolesnikov and Denis Kozhukhin – and on disc (Stephen Hough’s new recording is a good starting point for anyone wishing to explore the variety and range of Debussy’s piano music).

Debussy: La Plus que Lente

His piano music is challenging to play, even the “easier” works. First, I think it is important to dismiss the notion that his music is “dreamy and ethereal” (the inaccurate and banal description given to it in a segment marking the composer’s centenary on Radio Four’s Today programme on 24 March). It is not a Monet painting in musical form. In fact, his music is tightly structured (for more detailed analysis on this, see the writings of Roy Howat) and intellectually rigorous; paradoxically, it is this rigour which gives his music its uniquely delightful spontaneity and improvisatory qualities.

No other composer feels to me more improvised, more free-flowing. But then the player is conscious of a contradiction as the score is studied more closely: Music that sounds created in the moment is loaded with instructions on how to achieve this.

– Stephen Hough, concert pianist

Physically, much of his piano music demands that the pianist thinks in horizontal terms and forget that the piano is a machine of springs, wood and wires. Working on the Sarabande from Pour le Piano with my then teacher, in preparation for my first diploma, she urged me to forget that my arms had bones in them and to imagine instead two thick rubber bands of infinite freedom and softness.

Claude Debussy: L’isle joyeuse (Mathilde Handelsman, piano)

While some works utilise sound washes akin to Monet’s brushstrokes – blurred lines and veiled textures – others have a clarity of expression with glittering virtuosic figurations, remarkable pianistic effects and distinct layers of musical colour (Pagodes, l’Isle Joyeuse, Jardins sous la pluie or Pour le Piano, which closes with a Baroque-inspired Toccata requiring extreme clarity of articulation on the part of the performer).

… the colour that only he could get from his piano. He played mostly in half-tint but, like Chopin, without any hardness of attack. […] His nuances ranged from a triple pianissimo to forte without ever becoming disordered in sonorities in which harmonic subtleties might be lost

– Marguerite Long, pianist

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter