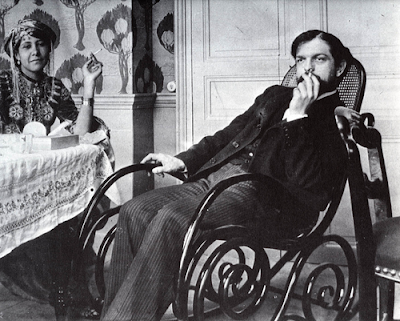

Debussy at the piano

Correspondances (Correspondences)

La Nature est un temple où de vivants piliers

Laissent parfois sortir de confuses paroles;

L’homme y passe à travers des forèts de symboles

Qui l’observent avec des regards familiers.

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent

Dans une ténébreuse et profonde unité,

Vaste comme la nuit et comme la clarté,

Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent…

Nature is a temple where living pillars

Sometimes unleash a confusion of words;

Man traverses it through forests of symbols

Which observe him with knowing glances.

Like extended echoes which mingle far away

In a mysterious and profound unity,

Vast as the night and as light,

Perfumes, colors and sounds answer each other…

Charles Baudelaire

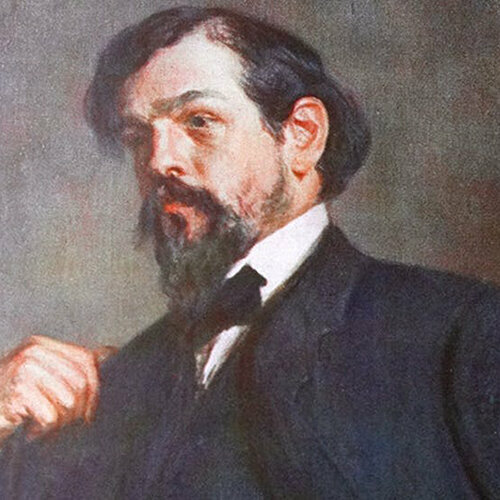

Debussy’s settings of Baudelaire, as you can easily hear, shimmer with the sensuous musical glow of Richard Wagner. In fact, Debussy made two pilgrimages to Bayreuth, and he responded positively to Wagner’s sensuousness, mastery of form, and striking harmonies. It has been suggested that while Debussy was no traditional heir to Wagner in Pelléas et Mélisande,“his possession and transformation of Wagner give him substantiality, signification, and depth.” Of course, Arnold Schoenberg vehemently disagreed and wrote, “Here is a remarkable fact, as yet unnoticed: Debussy summons to the Latin and Slav peoples, to do battle against Wagner, was indeed successful; but to free himself from Wagner—that was beyond him.” Without doubt, Debussy was searching for what Eric Satie called “a music of our own—preferably without sauerkraut.” In his Ariettes Oubliées on texts of Verlaine, Debussy employed alternatives to Wagnerian chromaticism by introducing modality and sliding parallel chords. In the process he created one of his most radiant alliances between poetry and music.

Claude Debussy: Ariettes Oubliées

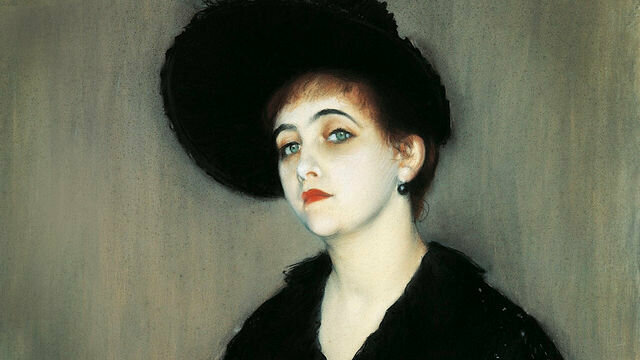

Paul Verlaine (1844-1896), poète français.

Claude Debussy: Suite Bergamasque

In 1903, Debussy remarked, “Wagner was a beautiful sunset mistaken for a dawn. There will always be periods of imitation or influence whose duration and nationality one cannot foretell—a simple truth and a law of evolution. These periods are necessary to those who love well-traveled and tranquil paths. They permit others to go much further.” Much has been written about Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune with regard to Mallarmé’s extended poem and Debussy’s musical setting. Regrettably, it’s still a matter of convention to read Debussy’s score as a direct parallel to Mallarmé’s poem. Debussy rather forcefully wrote 2 years after the premiere of the work. “The Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune dear Sir, might it be what remains of the dream at the tip of the faun’s flute? More precisely, it is a general impression of the poem, for if music were to follow more closely it would run out of breath.” Although the number of lines of the poem is identical to the number of measures in the score, it is clearly not a word-by-word translation. One thing for sure, the spell of Richard Wagner was broken for good, and Pierre Boulez decidedly claimed, “Modern music was awakened by L’après-midi d’un faune.”

In 1903, Debussy remarked, “Wagner was a beautiful sunset mistaken for a dawn. There will always be periods of imitation or influence whose duration and nationality one cannot foretell—a simple truth and a law of evolution. These periods are necessary to those who love well-traveled and tranquil paths. They permit others to go much further.” Much has been written about Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune with regard to Mallarmé’s extended poem and Debussy’s musical setting. Regrettably, it’s still a matter of convention to read Debussy’s score as a direct parallel to Mallarmé’s poem. Debussy rather forcefully wrote 2 years after the premiere of the work. “The Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune dear Sir, might it be what remains of the dream at the tip of the faun’s flute? More precisely, it is a general impression of the poem, for if music were to follow more closely it would run out of breath.” Although the number of lines of the poem is identical to the number of measures in the score, it is clearly not a word-by-word translation. One thing for sure, the spell of Richard Wagner was broken for good, and Pierre Boulez decidedly claimed, “Modern music was awakened by L’après-midi d’un faune.”

Claude Debussy: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

Thank you for this research. He looks unhappy. His music is my favorite as it reaches a place inside me which nothing else can achieve.