After listening to a number of beautiful Piano Trios, Quartets, and Quintets, it’s time to take a closer look at Piano Sextets. As the name implies, piano sextets are scored for piano and five other instruments. However, there really is no standard grouping of instruments with that name.

Piano Sextet

We do know, however, that the piano sextet with strings was rather popular in the first half of the 19th century, most commonly in an ensemble consisting of piano, string quartet, and double bass. In such groupings, the piano is often at the centre of the music.

The piano can be combined with a variety of instruments, including winds or mixed ensembles of strings and winds. So let’s get started with a blog featuring the 10 most beautiful piano sextets in classical music. And why not start with one of the greatest pieces in this particular genre, the Mendelssohn Piano Sextet in D Major, Op. 110.

Felix Mendelssohn: Piano Sextet in D Major, Op. 110

One of the greatest musical prodigies in classical music, Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), took lessons from the famous Carl Friedrich Zelter. He was the founder of the Royal Institute for Church Music in Berlin, and he also taught Giacomo Meyerbeer, Otto Nicolai and Carl Loewe. Zelter was an accomplished composer of Lieder, Cantatas and a host of smaller piano pieces, and in his teachings, he communicated the compositional techniques of his predecessors rather than conveying his own compositional style.

The young Felix Mendelssohn

During his apprenticeship with Zelter, and at the age of 15, Mendelssohn created some of his most intimate and original works, among them the Sextet Op. 110. First published and performed ten years after the composer’s death, the unusual scoring actually hints at Mendelssohn’s disguised attempt to write a piano concerto.

The opening “Allegro vivace” opens with a brief ensemble introduction before the piano gently traces a beautifully balanced melody. The stylistic influences of Mozart, Hummel and Beethoven are passionately synthesised throughout this movement and emerge prominently in the contrasting second theme and a meandering developmental section. Polite conversation between the pianist and the ensemble characterises the “Adagio,” while the “Menuetto” sounds a greater depth of musical expression. The concluding “Allegro” features the pianist prominently, with the ensemble only offering minimal resistance to the virtuoso pianistic escapades.

Ferdinand Ries: Piano Sextet, Op. 100

Ferdinand Ries

Ferdinand Ries: Piano Sextet, Op. 100 (Ensemble Concertant Frankfurt)

Ferdinand Ries (1784-1838) is well remembered as one of Beethoven’s piano students. However, he was also a prolific composer, writing three operas, two oratorios, eight symphonies and literally hundreds of pieces for piano and chamber music. Did you know that he also composed twenty-six string quartets? Ries had to abruptly depart from Vienna as he was conscripted for service in the Austrian army, and he made his way to London.

In his chamber works, Ries loved experimenting with the number of instruments and in matters of instrumentation. He first tried his hand at a piano trio, later added a piano quintet, and finally, the piano sextet Op. 100. The work probably dates from 1817, and it was published three years later in 1820.

Scored for piano, two violins, viola, cello, and double bass, the Grand Sextet seems to harbour almost symphonic ambitions in the opening “Allegro.” Agitated passages are juxtaposed against moments of reflection, and the piano contributes in an improvisatory way. The “Andante” builds a set of variations on the popular Irish tune “The Last Rose of Summer,” while the concluding “Adagio-Allegro” is a light and frisky rondo movement with touches of Beethoven and Mendelssohn.

William Sterndale Bennett: Piano Sextet in F-sharp minor, Op. 8

William Sterndale Bennett

William Sterndale Bennett: Piano Sextet in F-sharp minor, Op. 8 (Villiers Quartet; Leon Bosch, double bass; Jeremy Young, piano)

William Sterndale Bennett (1816-1875) was described as “a most brilliant artist” by none other than Robert Schumann. And Felix Mendelssohn declared in 1836, “I think him the most promising young musician I know.” Bennett made several journeys to Germany, including extended visits to Leipzig, where he dined with “Mendelssohn, Ferdinand David, and a Mr. Schumann, a musical editor, who expected to see me a fat man with large black whiskers.” While Bennett’s relationship with Mendelssohn remained formal, his friendship with Schumann was genuine.

Scholars acknowledged Bennett’s piano concertos as “among the finest embodiments of the classical spirit between the concertos of Beethoven and those of Brahms.” To be sure, Bennet was a “pianist’s musician” who recognised the instrument’s natural potential, “creating fabrics of nuanced tone colours, and intended his personal harmonic language less for the public than for the connoisseur.

Bennet composed the piano sextet in 1835, and it first sounded at the Royal Academy of Music in 1838. Using the same scoring as Mendelssohn and Ries, the weight of this work resides in a rather brilliant piano part, with the strings given a somewhat supportive role. The influence of Mendelssohn is ever present in the opening “Allegro,” while the scherzo contrasts a rhythmic idea with a broader lyrical theme in the trio. The slow movement seems influenced by Louis Spohr, and a tuneful “Finale” provides a spirited conclusion.

Mikhail Glinka: Piano Sextet

Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857) has been described as a “dilettante of genius.” His compositions are widely considered the foundation of Russian music, but he primarily wrote them while living and traveling in Western Europe for 23 years. He eventually enjoyed much popularity in Paris, Berlin, and other European capitals.

During his younger years, Glinka spent a good amount of time in Italy, taking composition lessons with Francesco Basili and meeting up with Bellini in Naples. While residing in Milan in 1832, Glinka was preoccupied with the idea of writing an opera. A frequent visitor to La Scala, Glinka fell under the spell of Donizetti and became infatuated with the married daughter of his physician. In fact, Glinka was besotted.

G. Goravsky: Mikhail Glinka, 1869

Although she was an amateur musician, she was a brilliant pianist with a sparkling technique. As Glinka later writes, “the similarity of our upbringing and our passion for the same art could not but bring us together. Because of her interest in the piano I began for her a “Sestetto Originale.” Titled the “Grand Sextet”, the work nevertheless sounds almost like a piano concerto. The opening “Allegro” creates a highly romantic mood, and it is followed by a dreamy second movement, Barcarole. Passions run high in the energetic “Finale,” which musically glances back to the beginning of the work.

Ernő Dohnányi: Sextet in C Major, Op. 37

Let’s start mixing things up a bit by turning to the Hungarian composer Ernő Dohnányi (1877-1960). His Sextet in C Major is scored for the unusual combination of piano, string trio, horn and clarinet. It originated in 1935 during a lengthy period of illness, during which Dohnányi was bedridden with a deep-vein thrombosis for several months. The premiere took place in Budapest on 17 June 1935, and a reviewer wrote, “One of the sextet’s greatest values is that it is melodically original. Every tune is invented, not borrowed, and not based on a quotation.”

Ernő Dohnányi

The Sextet would turn out to be Dohnányi’s last chamber music work. As a commentator writes, “Dohnányi takes us on an exhilarating musical journey, filled with late Romanticism’s rich harmonies and sweeping melodic lines.” The opening “Allegro” almost sounds like a tribute to Franz Liszt as an ominous motif, which constantly transforms itself and recurs throughout the movement.

If Liszt was the inspiration for the opener, Dohnányi turns to Mahler for his “Intermezzo.” The hazy and atmospheric opening is shattered by a martial march reminiscent of some Mahler “Wunderhorn” settings. The music brightens considerably in the set of variations which includes a scherzo-like Presto. The score ends with a good-humoured and infectious jazz-style parody.

George Onslow: Sextet No. 1 in E-flat Major, Op. 30

George Onslow

George Onslow: Sextet No. 1 in E-flat Major, Op. 30 (Ensemble Initium; Ensemble Contraste)

While George Onslow (1784-1853) might not be a household name today, his infectious and lovely lilting music was highly regarded in his day. He was a student of Jan Ladislav Dussek and Johann Baptist Cramer, and “he acquired in just a few years highly brilliant performance capabilities, an artiste’s virtuosity, and a fine sonority. His love for the piano was true, sincere, without reserve, and he loved it for the sound it emitted, for its lively scales, for its brilliant arpeggios.”

Predictably, Onslow composed a good deal of piano music, but he also wrote some fine chamber music which prominently featured the piano. His Sextet Op. 30, composed in 1825, was actually his first attempt at a work for large formation with piano. The composition is dedicated to Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and a commentator noted it ranged from “Beethovenian classicism to a romanticism fairly close to that of Schubert and Mendelssohn.”

Onslow offered his sextet for variable instrumentation, but originally, it was scored for wind instruments and piano. As expected, the piano takes a leading role, yet the concertante writing is paired with the intimacy of chamber music. Delicate arpeggios sound in the introduction to the opening “Allegro,” while the joyful “Menuetto” is based on a peasant dance. A gentle and lyrical theme initiates the “Andante with variations,” with the piano ever-present, and a stately “Finale” concludes one of Onslow’s most popular works.

Ernest Chausson: Concerto in D Major, Op. 21

Don’t let the title fool you, as Ernest Chausson’s “Concerto in D Major,” is essentially a piano sextet featuring the piano, a violin, and a string quartet. What Chausson apparently told us in the title is that the piece is written in the concerto grosso fashion, with the violin and piano featuring as solo instruments and the string quartet as the orchestra.

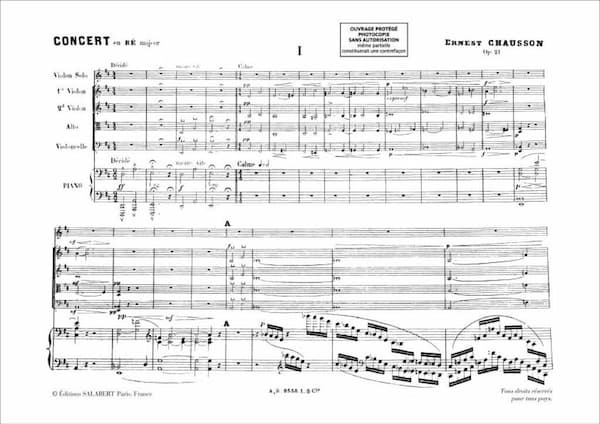

Ernest Chausson’s Concerto in D Major, Op. 21 music score

The solo aspects of the piano are very apparent, and even the accompaniment passages are intricate and highly demanding. Add to that a heavily chromatic texture and lyrical expressiveness, and you arrive at a work that nevertheless clings to a chamber-music framework in terms of communications between the solo duo and the quartet.

The slow introduction to the opening movement properly presents a three-note motif, which becomes the basis for the main theme. That main theme is taken by the violin and vigorously supported by the piano. Finally, the string quartet makes a grand entrance, and although there is much development throughout, the movement ends calmly. The influence of Debussy sounds in the brief Sicilienne, followed by a deeply melancholy “Grave” movement. The energetic “Finale” is virtuosic and brilliant, and true to the work’s title.

Louise Farrenc: Sextet in C minor, Op. 40

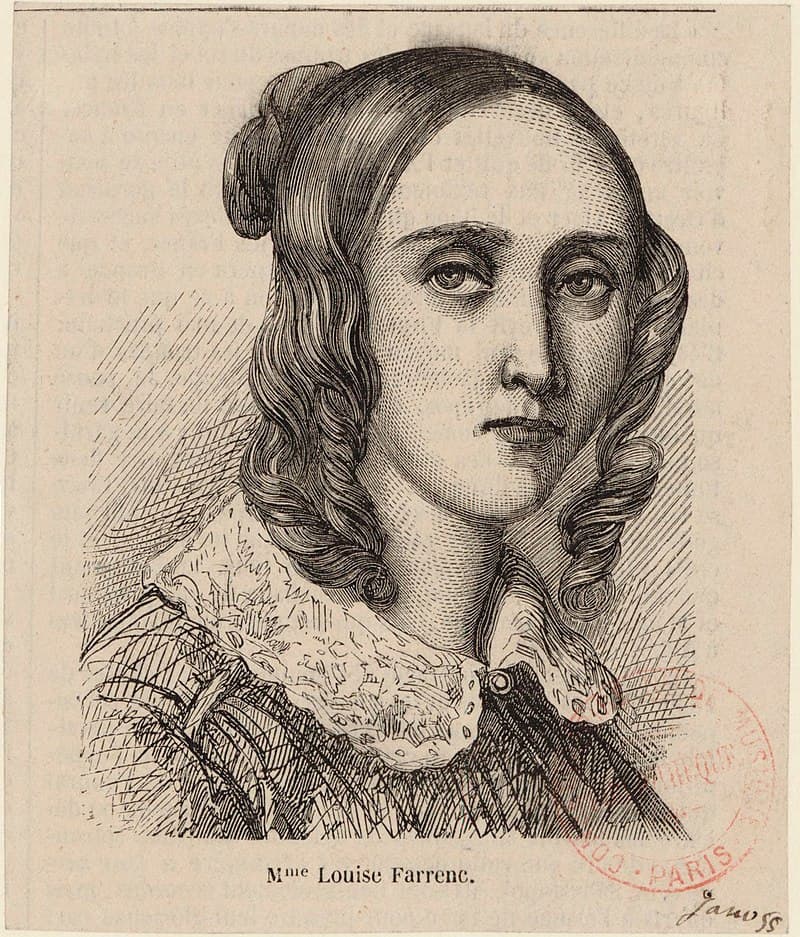

Louise Farrenc, 1855

Louise Farrenc: Sextet in C Minor, Op. 40 (Stuttgart Wind Quintet; Gitti Pirner, piano)

Here is a bit of trivia. Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) is considered the first composer ever to write for the combination of piano and wind quintet. She was a student of Ignaz Moscheles and Johan Nepomuk Hummel, and since classes at the Paris Conservatoire were not open to women, she privately studied with Anton Reicha. Finally, she was appointed professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire in 1842, and remained in that position for 30 years.

Farrenc had closely studied the quintets by Mozart and Beethoven, works well known and loved in Parisian circles. She added a flute to the instrumentation, probably because Reicha had published 24 wind quintets to great acclaim.

Farrenc treats the wind quintet as a quasi-orchestral ensemble, “which supports the sparkling piano part that is reminiscent of Hummel’s concertos.” The outer movements combine Beethoven’s earnestness with the delicacy of Mendelssohn. The central movement exudes a serenade-like intimacy, and the “richly melodious writing deftly brings out the distinctive qualities of each wind instrument.”

Bohuslav Martinů: Piano Sextet

Martinů in the US, 1945

Bohuslav Martinů: Piano Sextet, H. 174 (Jan Riedlbauch, flute; Vlastimil Mareš, clarinet; Jurij Likin, oboe; Lumír Vaněk, bassoon; Svatopluk Čech, bassoon; Ivan Klánský, piano)

A scholar writes, “there is a strong and almost visceral relationship between French music and wind instruments. More than any of its European musical counterparts, France has established a superb tradition of wind-playing, and it is home to many of the world’s foremost wind instrument makers.” Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) found himself in Paris in 1929, and he was immediately impressed with the high standards of French woodwind playing.

Once you add the liberating influence of Foxtrot, Tango, Charleston, and jazz, we arrive at one of Martinů’s most original compositions, his piano sextet. Martinů removed the horn from the woodwind quintet and added the piano and a second bassoon to create a highly versatile ensemble. A bluesy clarinet sounds in the “Preludium,” and the “Adagio” features richly-scored passages within soft religious overtones. The “Divertimento II” is actually titled “Blues” and imitates a saxophone while also featuring an episode of stride piano. And just listen to the piano cadenza in the “Finale.”

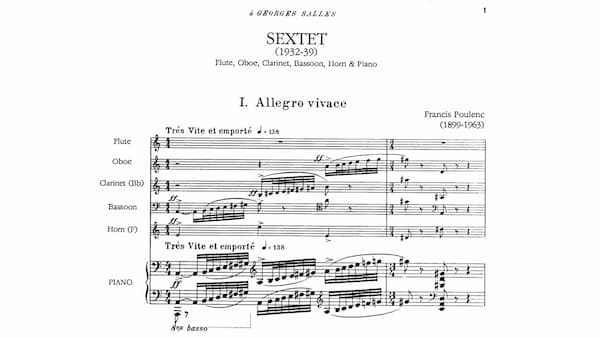

Francis Poulenc: Sextet

Francis Poulenc: Sextet music score

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963), the youngest and most prominent member of Les Six, composed his Sextet in 1932. He just loved chamber music and described the work as “chamber music of the most straightforward kind: a homage to the wind instruments I have loved from the moment I began composing.” Poulenc did not like the first effort and revised the score in 1939, with the final version performed in 1940.

The Sextet is quintessential Poulenc. Flamboyant and comical on the outside, it does have a rather melancholic core. A toccata-like introduction presents the motto theme that recurs in all three movements. The opening movement sounds harsh rhythms against songlike lyricism, and the second movement has plenty of melodic charm. As expected, the “Finale’ begins boisterously but ends in a very calm coda recalling the motto theme.

I trust you’ve enjoyed this little excursion into the world of the piano sextet and the 10 most beautiful works in that genre—obviously, that’s a matter of taste. Please stay tuned as a blog on the 10 most beautiful string sextets is coming up shortly.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter