“Ideas came to me with such rapidity”

Anton (Antoine) Reicha

You most likely have come across the composer Anton (Antoine) Reicha (1770-1836) in a footnote in a book on Beethoven. They were teenage buddies in Bonn, and even played in the same orchestra. The Bonn Hofkapelle was under the direction of Anton’s paternal uncle Josef Reicha, and Anton played the flute and violin and Beethoven the viola. The two composers, both coincidentally born in 1770 would remain on friendly terms.

Anton Reich was not born in Bonn, but in Prague. However, his father died when the boy was just 10 months old, leaving him in the custody of his mother who had little interest in her son. At the age of 10, Anton ran away from home and ended up with his uncle Josef, a virtuoso cellist, conductor and composer. Anton was soon adopted, and Josef taught him violin and piano, and his wife taught him French and German. Anton also studied the flute, and apparently against his uncle’s wishes he dabbled in composition and entered the University of Bonn in 1789. Anton met Haydn in the early 1790s in Bonn and again in Hamburg in 1795, where he was making a living teaching harmony and compositions.

Antoine Reicha: String Quartet in C minor, Op. 49, No. 1 (Kreutzer Quartet)

Anton (Antoine) Reicha, 1815

Between 1799 and 1801 Reicha was trying to gain recognition as an opera composer in Paris. Although a number of symphonies met with some success, he could not get his Hamburg librettos accepted and he was unable to find suitable dramas in Paris. When both the Théâtre Feydeau and the Salle Favart closed in 1801, he left for Vienna. He quickly renewed his acquaintance with Haydn and his friendship with Beethoven. He also studied composition and theory with Antonio Salieri and Johann Georg Albrechtsberger. Vienna proved a fertile ground for Reicha, and he wrote in his memoirs “The number of works I finished in Vienna is astonishing. Once started, my verve and imagination were indefatigable. Ideas came to me so rapidly it was often difficult to set them down without losing some of them. I always had a great penchant for doing the unusual in composition. When writing in an original vein, my creative faculties and spirit seemed keener than when following the precepts of my predecessors.” Reicha composed roughly 50 pieces during his stay in Vienna, including a good number of didactic and music theoretical works.

Antoine Reicha: 6 Fugues, Op. 81 (Henrik Löwenmark, piano)

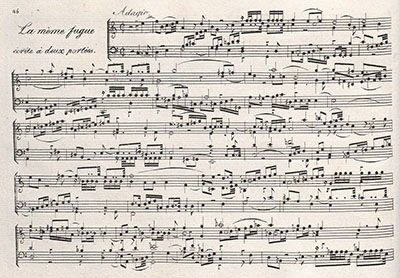

Reicha’s Fugue

Reicha had always stayed in touch with his Parisian friends and colleagues, and in 1805 he introduced Baillot and Cherubini, who were traveling in Napoleon’s entourage, to Haydn. Thanks to Napoleon, things were becoming unsettled in Vienna, and Reicha traveled to Leipzig and Prague before returning to Vienna. However, since Austria was once again preparing for war, Reicha left for Paris and was welcome home by Louis Adam and Sébastien Erard. Reicha quickly felt at home in the country, which he was to adopt as his own. His musical temperament and his manner of living were well suited for the Parisian environment. As he writes, “What did contribute to the high repute I gained in France were the large number of pupils I trained there, the teaching manuals I published, and especially the 24 great quintets for wind instrument which I composed there and had performed.” He felt that in the Quintets he was “formulating a new medium of expression, which would one day take its place beside music for string ensemble.” He also published a number of pedagogical manuals for teaching all branches of musical composition.

Antoine Reicha: Wind Quintet in D Major, Op. 91, No. 3 (Westwood Wind Quintet)

Reicha’ s Etude No. 20

Reicha continued to dabble in opera, but to his dismay, they all failed. As he dejectedly wrote, “it would be sheer folly if I were to busy myself further with operas, dramatic music, and plays. I shall leave these matters to all those who have nothing better to do.” Instead, he was appointed Professor of Counterpoint and Fugue at the Paris Conservatoire in 1818. Using his own textbooks, Louise Farrenc, Franz Liszt, and Hector Berlioz became his students, as did Charles Gounod and Pauline Viardot. Berlioz later wrote, “Reicha was an admirable teacher of counterpoint who cared about his pupils and his lessons were models of integrity and thoroughness.” Even Chopin considered becoming Reicha’s student when he arrived in Paris, but in the end decided against it. Among Reicha’s students we also find the young César Franck.

Tomb of Reicha at Pere-Lachaise cemetery, Paris

Reicha stayed in Paris for the rest of his life, and became a naturalized citizen of his adopted country in 1829. In 1831 he was awarded the “Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur,” and welcomed as a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1835. His death on 28 May 1836 resulted from an “inflammation of the breast,” and he was interred at the Père Lachaise Cemetery. Reicha was essentially unwilling to have his music published, and none of the advanced ideas he advocated in the most radical of his music and writings—including polyrhythm, polytonality and microntonal music—were accepted or employed by composers in the 19th century.

Antoine Reicha: Clarinet Quintet in F Major, Op. 107 (Karl Schlechta, clarinet; Maggini Quartet)