“J’écris ce qui me chante” – “I write of that which sings to me”

“J’écris ce qui me chante” – “I write of that which sings to me”

Francis Poulenc

In 1916 in Paris, Francis Poulenc (1899-1963), a largely self-taught composer, was introduced by a close friend to Adrienne Monnier’s bookshop ‘La Maison des Amis des Livres’ (The House of the Friends of Books), where the works of the contemporary authors, such as Ulysses by James Joyce, were read and discussed. There, Poulenc befriended a group of prominent avant-garde poets — Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Paul Eluard and Louis Aragon among them — whose poems he would put to music throughout his life.

Misia Sert (1872-1950), a leading Parisian society figure, patroness of the arts, inspiration and model to Toulouse-Lautrec, Bonnard, Renoir, and many others, was instrumental in furthering Poulenc’s development and career. She introduced him to the circle of the avant-garde painters, such as Picasso and Braque, to leading writers, such as Proust and Valéry, to prominent members of Parisian society (Chanel), and to Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes. Her circle of friends also included Eric Satie and Maurice Ravel, who would prove instrumental in Poulenc’s musical development.

Misia Sert (1872-1950), a leading Parisian society figure, patroness of the arts, inspiration and model to Toulouse-Lautrec, Bonnard, Renoir, and many others, was instrumental in furthering Poulenc’s development and career. She introduced him to the circle of the avant-garde painters, such as Picasso and Braque, to leading writers, such as Proust and Valéry, to prominent members of Parisian society (Chanel), and to Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes. Her circle of friends also included Eric Satie and Maurice Ravel, who would prove instrumental in Poulenc’s musical development.

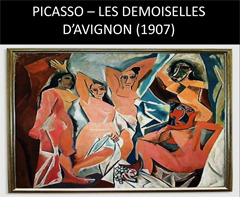

One of Poulenc’s first compositions, La Rapsodie Nègre (The Negro Rhapsody – 1917), had caught the attention of Igor Stravinsky, who encouraged and supported him. This composition also suggests a connection to Arnold Schönberg (Poulenc had met Schönberg, Berg and Webern on one of his travels to Austria), whose composition ‘Pierrot Lunaire’ uses a similar unconventional ensemble of flute, clarinet, violin, cello and piano. We should remember that African art, Jazz and Ragtime bands were very much en vogue in the early part of the 20th century — Jazz themes appear in Satie’s ballet ‘Parade’ in 1917 and in Milhaud’s ballet ‘La Création du Monde’ in 1923. Many artists had seen the important exhibitions of African art at the Musée Ethnographique de Trocadéro in Paris. Picasso’s visit in 1907 inspired his painting ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’, in which most of the faces are depicted as African masks, marking the beginning of Picasso’s cubist phase.

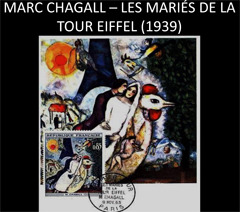

In dedicating La Rapsodie Nègre to Eric Satie, Poulenc clearly aligned himself with the avant-garde musical circle of the 1920’s. He also became a member of Jean Cocteau’s group ‘Les Six’ with Darius Milhaud, Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger and Germaine Tailleferre. ‘Les Six’ — the name reminiscent of the ‘Russian Five’, i.e., — Cui, Mussorgsky, Borodin, Balakirev, and Rimsky-Korsakov — as well as many other contemporary composers, reacted negatively to Wagnerism and to the late romanticism of the 19th century. Individually they contributed many works to the ‘modern’ canon, but they also created two acclaimed collective works, the ‘Album des Six’, and a ballet, ‘Les Mariés de La Tour Eiffel’, based on a text by Jean Cocteau, which, in 1938-39, became the subject of a surrealist painting by Marc Chagall of the same title.

In dedicating La Rapsodie Nègre to Eric Satie, Poulenc clearly aligned himself with the avant-garde musical circle of the 1920’s. He also became a member of Jean Cocteau’s group ‘Les Six’ with Darius Milhaud, Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger and Germaine Tailleferre. ‘Les Six’ — the name reminiscent of the ‘Russian Five’, i.e., — Cui, Mussorgsky, Borodin, Balakirev, and Rimsky-Korsakov — as well as many other contemporary composers, reacted negatively to Wagnerism and to the late romanticism of the 19th century. Individually they contributed many works to the ‘modern’ canon, but they also created two acclaimed collective works, the ‘Album des Six’, and a ballet, ‘Les Mariés de La Tour Eiffel’, based on a text by Jean Cocteau, which, in 1938-39, became the subject of a surrealist painting by Marc Chagall of the same title.

Figure humaine

LIBERTE

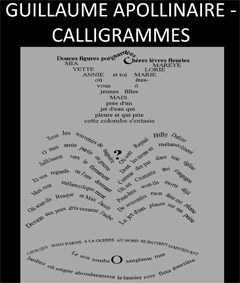

From 1918 until his death in 1963, Poulenc composed nearly 200 songs, most accompanied by piano, others by a chamber orchestra or a full orchestra. They were based on the poems of his circle of friends, Apollinaire, Eluard, Jacob and Aragon, whose war poem, Liberté is one of the most famous and most performed adaptations. It closes Poulenc’s cantata ‘Figure Humaine’, which was performed on the BBC in 1945 and had its French première in 1947. Cocteau noted that the genius of Poulenc was about the emphasis of the text. According to Cocteau, a poem, such as ‘Liberté’, gained in importance when sung, in that singing the text was in fact the only form possible of its full expression. Apollinaire’s poems, ‘Calligrammes’ push the visual elements of the text to the extreme, where the meaning of the poem is captured in its form. Themes overlap from one poem to the next — just as the musical modulations in Poulenc’s songs seem to overlap and repeat throughout the composition. Poulenc composes them as separate phrases and then assembles them again almost like a cubist collage, creating some of his most interesting compositions.

The poet Paul Eluard, also a member of the Salon d’Adrienne Monnier, became one of Poulenc’s closest friends. According to Poulenc, Eluard was the only Surrealist poet interested in music, as his following poem attests:

The poet Paul Eluard, also a member of the Salon d’Adrienne Monnier, became one of Poulenc’s closest friends. According to Poulenc, Eluard was the only Surrealist poet interested in music, as his following poem attests:

“Francis, I was not listening to myself

Francis, I am in your debt for having heard me

On a completely white road

In a vast landscape

Where the light is re-immersed

At night there are no more roots

The shadow is behind the mirrors

Francis, we dream of expanse

Like a child of endless games

In a starry landscape

That reflects only youth”

(cited in Harmonic Classics: Francis Poulenc – Melodies sur les Poèmes de Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Eluard & Federico García Lorca, Chansons Gaillardes)

Le travail du peintre, FP 161

As noted above, Poulenc was very much inspired by the visual elements of Apollinaire’s poems. In his song cycle ‘Le Travail du Peintre’ (The Work of the Painter), Poulenc puts paintings by Picasso, Chagall, Braque, Gris, Klee, Miró and Villon directly into musical form. One of Poulenc’s verses on Chagall reads:

| “Ane ou vache coq ou cheval Jusqu’à la peau d’un violon Homme chanteur un seul oiseau Danseur agile avec sa femme… | Donkey or cow rooster or horse Even the skin of a violin A singing man a single bird An agile dancer with his wife” |

The imagery evoked leads us not only to Chagall’s painting ‘Les Mariés de la Tour Eiffel’, but to many of Chagall’s other works in which similar images reappear. For Chagall, as in Poulenc’s compositions, musical imagery imitates the spatial breakdown of the pictorial elements, as if in a disjointed dance. Chagall brings various pictorial elements together on one canvas, which then re-appear in another painting, and so exceed the real homogenous space within one pictorial frame, just as Poulenc’s musical structures are stated and repeated in overlapping circles, such as in ‘Le travail du peintre’.

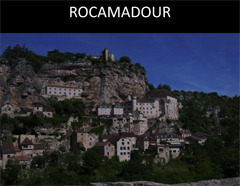

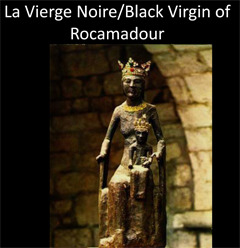

In 1936, after the death of a close friend, Poulenc made a personally transformational visit to one of the most important pilgrimage sites from the Middle Ages onward — Rocamadour, with its Sanctuary of the ‘Vierge Noire’ (Black Madonna). On my own many visits there, Rocamadour seemed to be a place beyond space and time — the village, unchanged by any modern building, clings to the rocks, and endless steps lead to the sanctuary, hewn into the native stone of the hillside. As one of the most important stops on the pilgrimage route to Northern Spain’s Santiago de Compostella, Rocamadour became equally important for Christians as pilgrimages to Rome and Jerusalem. Legend says that the preserved body of St. Amadour had been found at the site and that he himself carved the statue of the ‘Black Virgin — Enthroned Virgin and Child’, which was blackened by candles and torches throughout time — hence the name. Many miracles, attributed to St. Amadour and the Black Madonna, attracted famous penitents.

In 1936, after the death of a close friend, Poulenc made a personally transformational visit to one of the most important pilgrimage sites from the Middle Ages onward — Rocamadour, with its Sanctuary of the ‘Vierge Noire’ (Black Madonna). On my own many visits there, Rocamadour seemed to be a place beyond space and time — the village, unchanged by any modern building, clings to the rocks, and endless steps lead to the sanctuary, hewn into the native stone of the hillside. As one of the most important stops on the pilgrimage route to Northern Spain’s Santiago de Compostella, Rocamadour became equally important for Christians as pilgrimages to Rome and Jerusalem. Legend says that the preserved body of St. Amadour had been found at the site and that he himself carved the statue of the ‘Black Virgin — Enthroned Virgin and Child’, which was blackened by candles and torches throughout time — hence the name. Many miracles, attributed to St. Amadour and the Black Madonna, attracted famous penitents.

Rocamadour is also connected to the legend of Charlemagne and his trusted companion, Roland (he of the ‘Chanson de Roland’), who was killed in Roncevalles in the Pyrenées while returning from Spain. Roland wanted to save his famous sword, Durandal, from being taken by the attackers. With the help of Archangel Michael, the sword was flung through the air and embedded itself in the rock outside the Sanctuary of the Black Virgin, where a replica can be seen to this day.

The spirituality of Rocamadour impacted on Poulenc’s return to the spiritual aspects of Catholicism, and his music from this time onward gained in lyricism and reached a metaphysical dimension. His ‘Litanies à La Vierge Noire’ (Litanies to the Black Virgin), with a women’s choir and organ, his Mass in G -Minor, his Concerto in G minor for Organ, Strings and Timpani, his Stabat Mater and many other liturgical compositions from these years, are testaments to the mysticism and spirituality which Rocamadour and Catholicism represented for him. Late 19th century France had already seen a revival of Catholicism which would influence a generation of famous French Catholic writers, such as Paul Claudel, François Mauriac, André Gide and Georges Bernanos. Bernanos’ novels, such as ‘Sous le Soleil de Satan’ (Under the Sun of Satan), speak of a spiritual life, seeking the invisible through the visible, of a resolutely spiritualistic materialism (as suggested, for example by Matthias Grűnewald’s ‘Cruxificion’, which I had discussed in a previous Interlude article). Bernanos, in many of his works, also appeals to a certain ’medieval’ honor of a Christian Medieval knighthood, which Poulenc had sensed in Rocamadour.

Dialogues des Carmelites, FP 159

Dialogues des Carmelites, FP 159

Act III Tableaux 4: Salve Regina (Les Carmelites)

Poulenc’s opera ‘Dialogues des Carmélites’ (Dialogues of the Carmelites) was based on a play by Bernanos, itself inspired by the novella ‘Die Letzte am Schafott’/The Last on the Scaffold’ by Gertrud Freiin von Le Fort — which is in turn based on historical events during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror in 1793, when a group of Carmelite nuns were guillotined as enemies of the Republic. Poulenc’s opera, whose three acts are divided into twelve scenes with several orchestral interludes, is especially notable for the magnificent, haunting hymnal vocal writing. Particularly captivating is the last act — as the nuns are led to the (invisible) guillotine, their voices chant the ‘Salve Regina’, diminishing one by one – as each nun falls, with the sound of an ax in the background.

Again, Poulenc’s composition closely follows the lyrical and rhythmic flow of the text, which is also present in the text of Bernanos, who many consider one of the most distinctive and beautifully lyrical writers in the French language. Bernanos himself considered Poulenc’s music a supreme expression of the French language. Each word expressed in the music is unique, takes on weight, color and significance, and is enhanced in a musically structured phrase — which underscores Poulenc as the most literary of avant-garde composers.