This is the concluding episode in the series featuring music written by child prodigies.

Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn playing for Goethe

Before Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) reached the tender age of sixteen, he already had more than 150 surviving compositions to his name. Mendelssohn did not start composing until he had reached the age of ten, but he quickly became extremely prolific in his compositional efforts. At the beginning of 1820, he wrote a dozen chamber works, mostly scored for violin and pianos, and a trio in C minor. He was also writing a large number of solo piano works, with roughly thirty dating from this time. As Barry Cooper writes, “His most outstanding works for 1820, however, were those written for the stage. Two shorter works, a dramatic “Scene” and a “Lustspiel,” were followed by the substantial singspiel or comic opera Die Soldatenliebschaft, which consists of an overture and eleven numbers.”

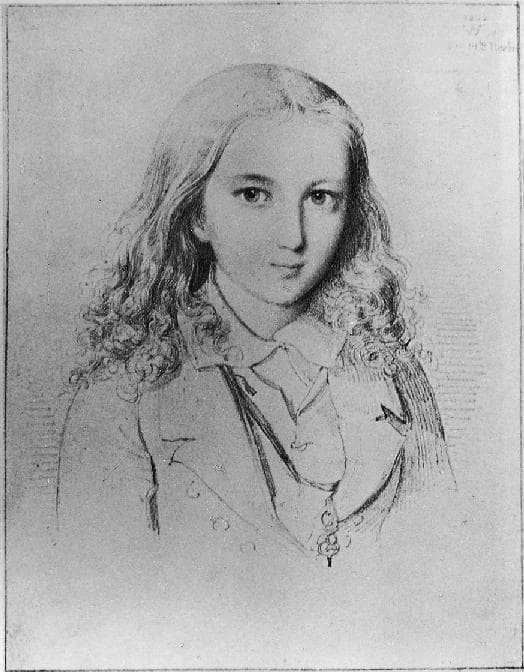

William Hensel: Portrait of Felix Mendelssohn, 1822

Mendelssohn composed prolifically throughout 1821, and he began a remarkable series of 13 String Sinfonias. Some of the later ones are “astonishingly well crafted and sophisticated, with rich and highly skilled part-writing and inventive scoring.” In addition, Mendelssohn continued writing for the stage, for orchestra, including some larger sacred works. Three piano quartets composed between October 1822 and January 1825 appear in print as Opp. 1-3, and his First Symphony was published a little later. The majority of his early works remained unpublished, as Mendelssohn did not consider them worth preserving. Luckily, he did not destroy them, and the manuscripts are preserved mainly in Berlin.

Felix Mendelssohn: String Symphony No. 10

César Franck

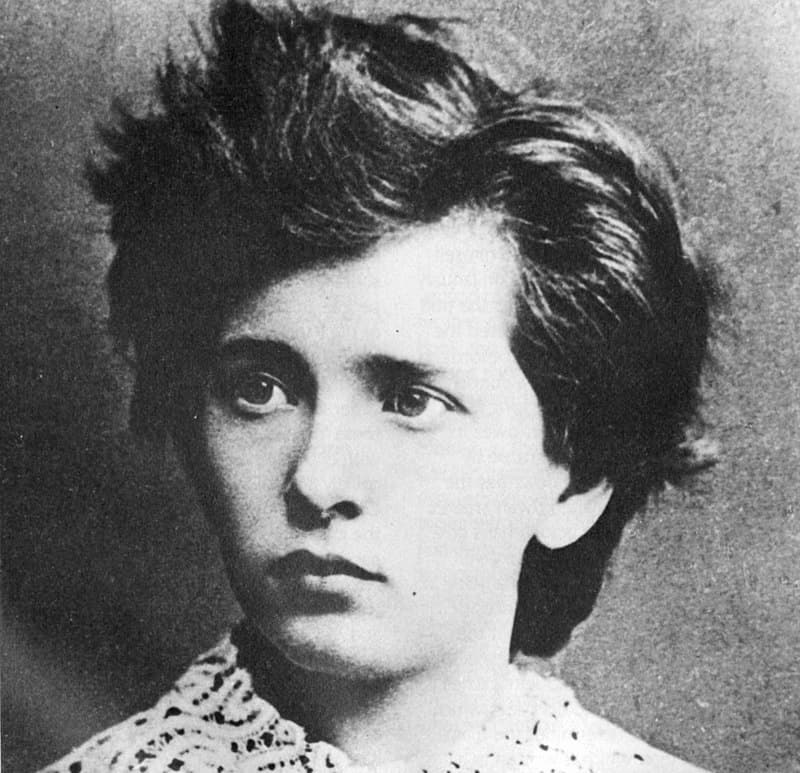

The young César Franck

César Franck (1822-1890) entered the Liège Conservatoire in 1830 to study with Antonin Reicha and Joseph Zimmerman. Around 1834, Franck began a remarkable series of extended compositions, including “many typical show pieces for the piano like brilliant variations and fantasies.” However, he also composed two sonatas, some fugues, and a now lost cantata. Another work that has seemingly been lost is his First Piano Concerto in F minor. Although it is referenced in contemporary accounts, it has been suggested that it was the invention of Franck’s father. However, César’s Second Grand Concerto, Op. 11, does in fact exist. The work dates from 1835 when Franck was only 12 years old. It carries no dedication, but “it is remarkable for the firmness of its writing, both in terms of the solo part and the orchestration.” Stylistically, it borrows from Hummel, Weber, and Chopin, with Beethoven looming large. Surprisingly, the piano does not have the last word. This is left to the orchestra and a closing oration of thirty-six measures. It is probable that Franck himself gave a partial performance of the work at the Athénée musical on 23 February 1837.

César Franck: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B minor, Op. 11 (Martijn van den Hoek, piano; Arnhem Philharmonic Orchestra; Roberto Benzi, cond.)

Carl Maria von Weber

Thomas Lawrence: Carl Maria von Weber, 1814

In his autobiographical sketch of 1818, Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) wrote to a friend. “Stimulated and encouraged by the friendly sympathy of the excellent Franz Danzi, I wrote an opera, Silvana, on Franz Hiemers’s new version of my earlier Waldmädchen.” Weber’s first compositions emerged in 1798 as a result of his study with Michael Haydn. Praised in a review in the newly established Leipzig journal “Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung,” Weber followed up with several more piano works.

Some other early efforts were lost, among them a number of string trios and part songs. However, far more significant are Weber’s first efforts at writing music for voices and orchestra. His first opera “Die Macht der Liebe und des Weins,” is lost, and the same is true of his second opera “Das Waldmädchen.” Supposedly, it tells the story of a dumb operatic heroine and her beloved, who is about to be forced into marriage with another woman madly in love with him. The opera was performed in Freiburg in 1800, just after Weber’s fourteenth birthday. That score disappeared, but as we learned from the composer, portions of the music found a new home in the opera Silvana.

Carl Maria von Weber: Silvana (Stefan Adam, baritone; Jurgen Dittebrand, narrator; Horst Fiehl, baritone; Sergio Gómez, bass; Andreas Haller, bass; Katja Isken, narrator; Anneli Pfeffer, soprano; Angelina Ruzzafante, soprano; Alexander Spemann, tenor; Peer-Martin Sturm, tenor; Volker Thies, tenor; Hagen Theater Opera Chorus; Hagen Philharmonic Orchestra; Gerhard Markson, cond.)

Carl Filtsch

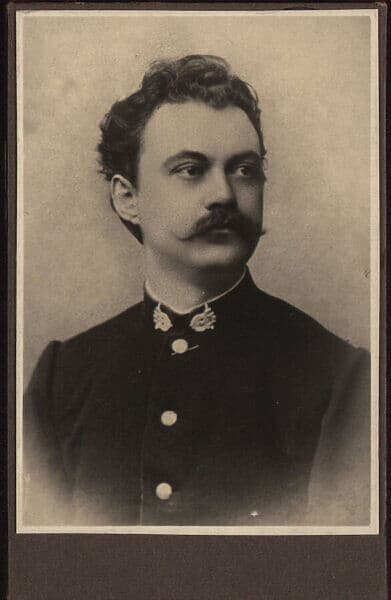

Carl Filtsch

When Franz Liszt first heard Carl Filtsch (1830-1845) play the piano, he dejectedly exclaimed, “When this little one begins to tour, I will have to close up shop.” Sadly, Filtsch was not able to fulfill this high promise as he died from tuberculosis at the age of only fourteen. Filtsch started piano lessons at the age of three and counted Sechter, Wieck, Liszt, and Chopin among his teachers. He launched his pianistic career with a tour in his native Transylvania at the age of six, and his earliest known composition dates from 1839.

Several of his works were published during his lifetime, but his portfolio also contains two unpublished compositions for full orchestra, an “Overture in D Major” and a “Konzertstück for piano and orchestra.” He composed the Konzertstück in B minor at the age of twelve, and it has been suggested that he may have intended a second and third movement as well. The work was thought to have been lost, but it was discovered in the hands of a private collector in England. The composer was preparing the premiere of his Konzertstück in Vienna during the winter of 1843/44 but fell ill and died only days shy of his fifteenth birthday.

Carl Filtsch: Concert Piece in B minor (Hubert Rutkowski, piano; Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Warsaw; Łukasz Borowicz, cond.)

Franz Liszt

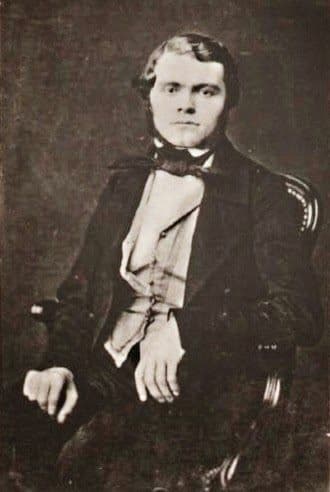

Franz Liszt ca.1827

When Franz Liszt (1811-1886) moved to Vienna to take lessons with Carl Czerny in 1821, he quickly composed his first published work, variations on Diabelli’s famous waltz. The composition appeared alongside variations by forty-nine other composers in July 1824. Liszt composed a number of works during this period, but the most notable work from this period is the opera Don Sanche, or “The Castle of Love.” The overture was performed in Manchester on 16 June 1825, and the complete opera premiered in Paris on 17 October 1825, five days before Liszt’s fourteenth birthday. Opinions about this work have been varied, “with some thinking it so good that they questioned whether the child could have written it,” while others have dismissed it out of hand. According to Cooper, “it displays much imagination, resourcefulness, and a thorough command of compositional technique. A great variety of moods is evoked by Liszt to suit the changing dramatic situation, and throughout the work the melodic charm is particularly noteworthy.” It has also been suggested that the skillful orchestration was produced with the aid of some outside assistance.

Franz Liszt: Don Sanche (The Castle of Love), S476/R13 (Gerard Garino, tenor; Júlia Hamari, mezzo-soprano; István Gáti, baritone; Katalin Farkas, soprano; Ildikó Komlósi, mezzo-soprano; Mária Zádori, soprano; Gabor Kallay, tenor; Hungarian Radio and Television Chorus; Hungarian State Opera Orchestra; Tamas Pal, cond.)

Georg Philipp Telemann

Georg Philipp Telemann

In his autobiography, Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) writes. “In elementary schools, I learned the usual things, but then I eventually took up playing on my own the violin, flute, and zither and entertained my friends with this music without even knowing anything about notes on a page. When I was ten, I began attending the Gymnasium, and in music, I had learned so much in only a few weeks that the cantor let me be his substitute for singing classes. I began composing myself, but without anyone knowing about this. Much emboldened, at the age of twelve, I got a hold of an opera from Hamburg, Sigismundus, and set it to music. It was performed on a hastily erected stage with me singing the role of the hero rather defiantly. I would love to see this score again if I were not in my right mind! Oh, but what storms I had to endure because of the opera mentioned above! Hordes of music haters came to my mother and tried to persuade her that I would become a charlatan, tightrope walker, minstrel, woodchuck trainer if I did not stop my involvement with music.” Telemann’s opera Sigismundus has regrettably been lost, but fortunately, the composer never stopped his involvement with music.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Wohl dem, der den Herrn fürchtet, TWV 1:1703a (excerpts) (Gudrun Sidonie Otto, soprano; David Erier, alto; Caroline Kang, cello; Karl Nyhlin, gallichone; Aleksandra Grychtolik, harpsichord)

Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni, Vienna, 1877

Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) might well have been one of the most productive of all child composers. Of roughly 303 original works listed in the thematic catalogue, almost half were composed before Busoni reached his 16th birthday. His earliest short piano composition dates from June 1873, followed by additional short and unpretentious piano pieces in quick succession. A three-movement piano sonata was completed in 1875, followed by a series of multi-movement instrumental works in the next few years. However, Busoni also composed a number of vocal works, both secular and sacred, ranging from Lieder to complete mass settings and a large-scale Requiem. The majority of Busoni’s early works do involve the pianos, and “nearly all exhibit an already well-developed style and thoroughly secure compositional technique. They are generally serious in character, and without the highly florid, decorative writing beloved of so many Romantic piano composers.” Rarely ambiguous in harmony, Busoni was strongly influenced by Bach, “with a rich vein of polyphonic thought often in evidence even where there is no actual imitative writing.”

Ferruccio Busoni: Violin Sonata in C Major (Cristiano Rossi, violin; Marco Vincenzi, piano)

Rued Langgaard

Rued Langgaard

10 April 1913 was a defining day for the 19-year-old Rued Langgaard (1893-1952), as the Berlin Philharmonic presented his First Symphony to a vast audience. His international debut was an overwhelming success, while in his hometown of Copenhagen his symphony had been rejected as unplayable. Langgaard grew up in a highly musical family, and he was perhaps the greatest talent Danish music had ever seen. He made his public debut by improvising on the organ at the age of 11.

Edvard Grieg was in the audience, and he was both “impressed and frightened by the boy’s unusual talent.” Langgaard started work on his First Symphony at the age of 14, completing the first four movements in 1908. He began work on the monumental final movement in 1909 and presented the work to the Danish Concert Society. The Society explained that the work lay well beyond the capabilities of the orchestra. As such, Langgaard travelled to Stockholm in hopes of securing a performance, but he failed to receive a positive response. Langgaard refined and polished the score and pronounced himself satisfied in April 1911. “Lasting about an hour, the work exhibits a rich and expressive late-Romantic style reminiscent of Bruckner or Richard Strauss, with much powerful use of brass instruments, but also many tender passages.”

Rued Langgaard: Symphony No. 1 “Klippepastoraler” (Pastorals of the Rocks) (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Sakari Oramo, cond.)

Karel Šebor

Karel Šebor

Karel Šebor (1843-1903) was a child prodigy who attended the Prague Conservatory from the age of 11. He studied the violin and composition, and by 1858 had written his first symphony in E-flat Major. This was followed by an orchestral overture in E Major in 1859. It has been suggested that he “must have composed other works before this, but no details have yet emerged.” Šebor gained a reputation as an excellent violinist, performing in chamber music concerts in and around Prague. However, in 1860, he was found to be suffering from a heart defect, and he left the conservatory and gave up any hope of pursuing a career as a violinist.

Šebor would subsequently become associated with Czech opera, as he was chorus master and second conductor at the Prague Provisional Theatre. His first opera The Templars in Moravia was staged with great success, and it established Šebor as a leading Czech composer. Šebor is considered “one of the most talented and significant of Czech Romantic composers. His creative style, which was founded upon French and Italian influences, especially Auber, Meyerbeer, and Bellini, was notable for its spontaneity, evocative and strongly lyrical melodic writing, and an acute sense of orchestral color.”

Karel Šebor: The Templars in Moravia, Act I: Excerpt (Ivan Kusnjer, baritone)

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Autographed photo of the young Erich Wolfgang Korngold

I want to finish this little survey of child prodigies in Classical Music with Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957), who might have been the most phenomenal musical prodigy of all time. At the age of 9, he played his cantata Gold to Gustav Mahler, who pronounced him a genius. Merely two years later he composed the ballet Der Schneemann (The Snowman), which caused a sensation at the premiere performance at the Vienna Court Opera in 1910. Various compositions for chamber ensemble and solo piano quickly followed, and Richard Strauss wrote, “One’s first reaction that these compositions are by a child are those of awe and concern that so precocious a genius should follow its normal development…This assurance of style, this mastery of form, this characteristic expressiveness, this bold harmony, are truly astonishing!”

By age 14 Korngold had completed his first orchestral composition, and finished his first two operas 3 years later. The musicologist Hermann Kretzschmar called him “phenomenal even among the exceptional cases of early musical development.” Korngold’s ability was highly suspect in Vienna, as it was claimed that it was impossible for a child of his age to compose such ravishing music. A biographer writes, “A skeptical populace concluded that this music could not have been written by an eleven-year-old boy, and suggested it must be by his father, the music critic Julius Korngold.” “If I could write such music,” explained Julius Korngold, “I would not be a critic.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter