Be forewarned: Three is an excellent score

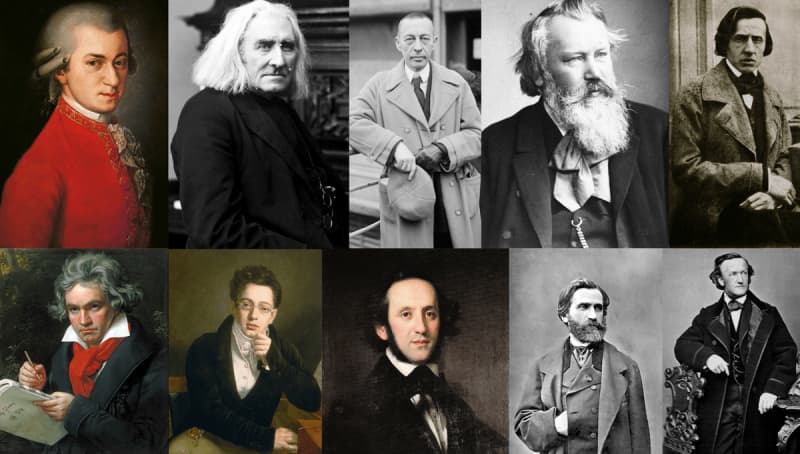

Recently, I heard a superb premiere of music by an 87-year-old composer. I wondered how many composers in their 80s have maintained similar creativity. To my surprise—and delight, as I’m in my 70s—I found ten. The music, much of it rarely performed, will exceed your expectations.

Count the pieces you’ve heard before and check your number against our scale at the end. And enjoy the music!

1. Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672): Schwanengesang

Heinrich Schütz

Heinrich Schütz is usually considered the most important German composer before Bach, celebrated for bringing the Italian style he learned from Giovanni Gabrieli in Venice to Germany. At a time when the average lifespan was 36, he lived to 86. Finally retired after writing more than 500 compositions, he wrote his Schwanengesang (Swan Song) in 1671. This monumental work consists of 11 motets based on Psalm 119, a twelfth motet on Psalm 100 with the Magnificat (My soul magnifies the Lord) and a thirteenth motet on the Nunc Dimittis or Song of Simeon (Lord, let your servant go in peace). The style consists of Netherlands-style modal polyphony with dissonant text-painting, often with two choirs for antiphonal glory in the Venetian style. This excellent recording by Musica Fiata doubles some voices with cornetti, violins or trombones, as Schütz would have done.

Heinrich Schütz: Schwanengesang, SWV 482-494 – 1st Motet (La Capella Ducale, Musica Fiata, Roland Wilson, cond.)

2. Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767): The Day of Judgment

Georg Philipp Telemann

No composer has been more prolific than Telemann, with his more than 3,000 compositions. When he became music director of five churches in Hamburg in 1721, Telemann also began producing public concerts. At the age of 81, Telemann composed his oratorio The Day of Judgment for such a public concert. Advertised as a “poem for singing with strong emotions,” its libretto laid out four “contemplations” for its main sections: the proclamation of the Last Judgment, a portrayal of the godless, the horror of the Judgment and the happiness of those in heaven. A closing chorale soothes the listener following the drama of the performance.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Der Tag des Gerichts, TWV 6:8 – The First Reflection: Der Herr kommt mit viel tausend Heiligen, Chorus (Siri Karoline Thornhill, soprano; Susanne Krumbiegel, alto; Tobias Hunger; tenor; Gotthold Schwarz, bass; Leipzig Bach Consort; Gotthold Schwarz, cond.)

3. Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764): Les Boréades

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Rameau became well-known in his 40s for his writings on music theory. At 50 Hippolyte et Aricie established his reputation in opera, and he devoted the rest of his life to that medium. In 1763, his last tragédie en musique, Les Boréades, had been copied and even placed on music stands for rehearsal. Mysteriously, it was never performed. Was it too difficult rhythmically for the musicians? We do not know. The score was subsequently lost and rediscovered, then staged at last in 1982 at the Aix-en-Provence Festival with John Eliot Gardiner conducting, creating a sensation. The music features vibrant dances, pre-Classic melody, a chaotic tempest and gala choruses.

Jean-Philippe Rameau: Les Boréades – Act III: Borée en fureur (Jennifer Smith, soprano; Philip Langridge, tenor; English Baroque Soloists; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.)

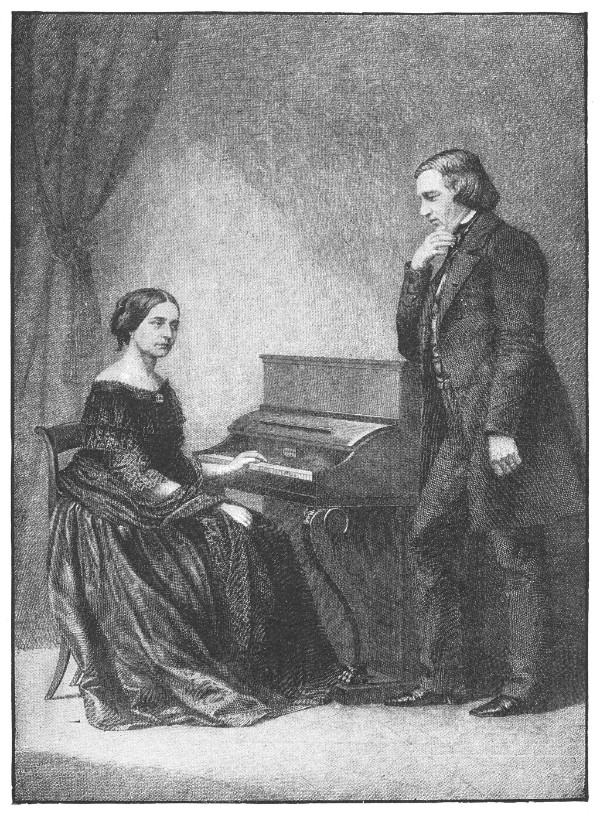

4. Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901): Te Deum from Four Sacred Pieces (Quattro Pezzi Sacri)

Giuseppe Verdi

At the age of 79, Verdi completed his final opera, the splendid comedy Falstaff. Two of his Four Sacred Pieces, Te Deum and Stabat Mater, were completed in his early 80s.

Verdi was not a practicing Catholic, saying that he believed in God but not in priests. The theater sounds through all his sacred music, whether the passages are loud or soft. That said, Verdi requested that the score of Te Deum be buried with him.

Te Deum is written for double choir, orchestra and soprano soloist—preferably a boy soprano. The music ranges from apocalyptic climaxes to whispers, often in close succession. The old recording below was conducted by Arturo Toscanini, who knew Verdi so well he consulted with him personally about the score. The performance illustrates Toscanini’s intensity and his constant attention to phrasing.

Giuseppe Verdi: 4 Pezzi sacri – No. 4. Te Deum (Robert Shaw Chorale; NBC Symphony Orchestra; Arturo Toscanini, cond.)

5. Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921): Clarinet Sonata in E-Flat Major, Op. 167

Camille Saint-Saëns

Saint-Saëns wrote his Clarinet Sonata at 86, in the last year of his life, along with his Bassoon and Oboe Sonatas. The Sonata contains a lyrical first movement, a sprightly scherzo and a virtuosic rondo reminiscent of Carl Maria von Weber. The piece could be described at various times as elegant, nonchalant, and brilliant. The third movement, the heart of the sonata, begins as a dirge and transforms into a vision of paradise.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Clarinet Sonata in E-Flat Major, Op. 167 – IV. Molto allegro (Richard Stoltzman, clarinet; Irma Vallecillo, piano)

6. Richard Strauss (1864-1949): Vier letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs)

Richard Strauss

Composed in 1948, Strauss’ Four Last Songs for soprano and orchestra are his last completed works. The title as well as the order of the songs was given by Strauss’ editor at Boosey & Hawkes. Set to three poems by Hermann Hesse and one by Joseph von Eichendorff, the songs meditate on the end of life and transfiguration with serenity and acceptance.

Frühling (Spring) rhapsodizes about youth, shimmering with light and an ecstatic line for the soloist. September celebrates an autumn garden, with accompaniment patterns and inner voices sounding like falling leaves. Beim Schlafengehen (Going to Sleep) features a gorgeous violin solo and an ecstatic rising soprano line as the soul ascends. And Im Abendrot (At Sunset) quotes the Transfiguration Theme from Strauss’ own Tod und Verklärung, the music becoming slower and slower to the end.

Renee Fleming – Strauss’ 4 Last Songs – Fruhling

7. Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971): Requiem Canticles (1966)

Igor Stravinsky

Stravinsky’s last completed score of consequence, Requiem Canticles, was played at his funeral in 1971. Although it was written five years before, when he was 83, Stravinsky’s wife, Vera, said, “He and we knew he was writing it for himself.”

Stravinsky called it “the first pocket Requiem,” as it lasts just 15 minutes. He had written a Mass in the 1940s; here he composed only the sections unique to the Mass for the Dead. It begins with a string prelude and ends with a postlude of bells reminiscent of his 1923 ballet Les Noces. An orchestral interlude splits the vocal movements—Exaudi, Dies irae, Tuba mirum, Rex tremendae, Lacrimosa, and Libera me—most of which are represented by a fragment of the text. As with his idol Tchaikovsky, every measure of his music can be danced, and both George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins choreographed Requiem Canticles.

Igor Stravinsky: Requiem Canticles (1966) – IX. Postlude (Stella Doufexis, contralto; Rudolf Rosen, bass; South West German Radio Vocal Ensemble; South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Gielen, cond.)

8. Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992): Éclairs sur l’Au-Delà… (Lightning Over the Beyond…)

Olivier Messiaen

The New York Philharmonic requested a short piece from Olivier Messiaen for its 150th anniversary in 1992; Messiaen responded with a 75-minute work of 11 movements scored for 128 instruments, including three ondes Martenot. Messiaen’s last composition took four years to write, 1987-1991, during which he was often in intense pain from back surgery.

Despite its scale, Éclairs sur l’Au-Delà… is transparent in texture and light in temperament. Messiaen’s writing follows its usual methods and themes—modes of limited transposition, palindromic rhythms, ecstatic Christianity and birdsong—in an astonishing array of textures.

Olivier Messiaen: Éclairs sur l’Au-Delà… – III. L’Oiseau-Lyre et la Ville-Fiancee (Bastille Opera Orchestra; Myung-Whun Chung, cond.)

9. Pierre Boulez (1925-2016): Dérive 2

Pierre Boulez

Both the story of Dérive 2 (1988-2006/2009) and the music itself are about constant transformation. Boulez dedicated the music to composer Elliott Carter for his 80th birthday in 1988. Boulez continued to expand the score, so Carter only heard the music at the age of 98, in 2006. Even then, Boulez worked on the music another three years, eventually creating 50 minutes of music.

Dérive 1 (1984) was built on a cryptogram, a set of six notes spelling out the last name of the conductor and music patron, Paul Sacher. Six chords were also developed, and Dérive 2 is also built on this framework. 11 instruments continuously play with this material. Textures are pointillistic, layered in rhythm, constantly being transformed through permutation.

Pierre Boulez: Dérive 2 (2006) (West-Eastern Divan Orchestra; Daniel Barenboim, cond.)

10. John Corigliano (1938- ): Tennessee Songs (2025)

John Corigliano

Read about Corigliano’s Tennessee Songs on poems of Tennessee Williams in my recent article. The premiere was on April 2, 2025, in Tucson, Arizona, with soprano Larisa Martinez and her husband, violinist Joshua Bell. No recording is yet available.

How Do You Measure Up?

I’ve heard none of these pieces.

You’re in good company—and about to discover some gems.

I’ve heard one piece.

Excellent! Now go find the other nine.

I’ve heard two pieces.

You’re officially a connoisseur. Or are you just pretending?

I’ve heard three pieces.

You either know your stuff—or got really lucky with a Spotify shuffle.

I’ve heard four pieces.

Where did you do your graduate work? Vienna? Berlin?

I’ve heard five pieces.

Have you considered donating your brain to musicology?

I’ve heard six pieces.

Are you sure you’re not just counting the same piece six times?

I’ve heard seven pieces.

You’ve either conducted an orchestra or are an orchestra.

I’ve heard eight pieces.

You’ve clearly frightened your streaming algorithm.

I’ve heard nine pieces.

Step away from the headphones and touch grass.

I’ve heard all ten.

Pinocchio? Is that you?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Intriguing. Even challenging. Four ain’t bad.

Not at all bad! I hope you enjoyed exploring some of the others.

Are these AI portraits? They don’t look anything like Strauss, Stravinsky, Messiaen, Boulez and Corigliano. Elliott Carter should have been included.

Thank you for your comment. Elliott Carter was indeed remarkable, writing lots of music into his 100s. Do you have a recommendation from his late output–particularly from his 80s? I’d love to discover more about him. As for the portraits, I’ll pass your note on to my illustrator.

Thank you. That was both informative and entertaining. I got seven !

Ms. Margaret, *I’m* impressed! Before I wrote this article, I would have scored six. And I have one up on other readers, who aren’t likely to have heard the premiere of Corigliano’s Tennessee Songs a few weeks ago.

Hi There – Congratulations – Musicology, at it’s finest. I had 2. It would be quite a satisfaction; if that turns out to be the average. I already tested my AI resources, when i asked them , if there aré recorded productions, presenting exclusively, the final compositions of the most successfull composers. But i came out empty. Would you entertain my inquiry? Best Regards

Thank you for your kind comment. I’ll hazard a guess: for the general public, the average would be somewhere under 0.1. For Interlude.HK readers, 2 may indeed be the average. Does the number really matter? Isn’t it all a journey?

I know of no such recordings focused on a variety of composers’ final compositions. Individually, there are many of late Beethoven or Liszt, for example. Perhaps you could produce such an album–but I suspect your pocketbook would come out empty. Best regards, Bruce

Great introduction to some intriguing composers and amazing variance in music through the centuries. I’m going to listen to more Renee Fleming now.

Thank you for your comment. What could be better than more Renee Fleming?

She recorded the Four Last Songs of Strauss twice, not including the many live performances you can find online: Christoph Eschenbach conducting Houston Symphony (1996) and Christian Thielemann conducting the Munich Philharmonic (2008).