Johann Sebastian Bach was born in present-day Germany in 1685. Before we dive into his music, here are a few things you should know about him first:

J.S. Bach © biography.com

- Music was Bach’s family business. Almost every man in his family was a professional musician. He passed that expertise down to his own children, and a few of them became well-known composers in their own right.

- His life was shaped by death and grief. His mother died when he was nine, and his father when he was ten. Then, his first wife died unexpectedly in 1720, leaving him a single father until he remarried a young singer the following year. Many of his twenty children died young, as well.

- Bach’s Lutheran faith was deeply important to him. This manifested in his career. For much of it, he was a church musician who wrote music for performance in a sacred context.

- Bach is known for his massive output, his obsession with creating sets of music, his mathematical precision, and his brilliant composition technique.

Here are a selection of works by Bach to get you started:

Little Fugue in G-minor – Organ – 1709

If you’re going to listen to Bach’s music, sooner or later, you’re going to come across a fugue.

A fugue is a piece of music that begins with a brief melody, then is repeated with alterations according to a series of predetermined compositional rules. It’s a bit like a more complicated version of the song Row, Row, Row Your Boat.

This is one of Bach’s more famous fugues, written when he was in his mid-twenties and working in Arnstadt as a church musician. During this time, he had access to a great organ, and wrote a lot of music for that instrument.

Here’s a bit of trivia: apparently, during Bach’s time in Arnstadt, his standards were so high that he antagonized the other church musicians to the point where one bassoonist attacked him!

Little Fugue in G-minor – Orchestra

Here’s the same piece but rearranged for a modern orchestra by a conductor named Leopold Stokowski. (He was the conductor in Disney’s “Fantasia.”)

When listening to Bach, it’s important to remember that every generation has their own take on his music.

In the early part of the twentieth century, it was considered acceptable to rewrite Bach’s music for a massive modern ensemble he could never have imagined.

Later, something called historically informed performance practice, sometimes abbreviated as HIPP, became popular. Historically informed performance practice is a movement that seeks to adhere as closely as possible to what Bach might have heard in his own era.

These ever-changing priorities can make different recordings of Bach’s music sound vastly different from each other. So when you’re intrigued by something he wrote, it’s worth it to “shop around” to find a performance that touches you.

What do you like better, the original version for organ or the later orchestral version?

Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 – 1710s

In the 1710s, Bach worked as a director of music at the ducal court in Weimar. This meant that he was tasked with creating a lot of secular music, as opposed to the church music he had been writing.

In 1721 he collected six pieces for instrumental ensembles and combined them into a collection that came to be known as the Brandenburg Concertos.

He sent this collection to the Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt, hoping for a job offer or a financial token of appreciation, but the works were never acknowledged. Indeed, when the Margrave died in 1734, the manuscripts were sold for the modern equivalent of $24.

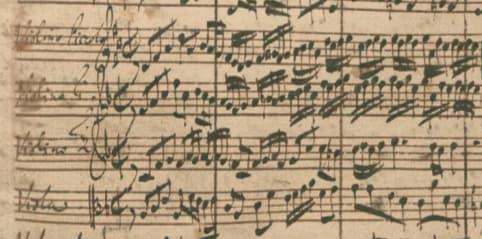

Manuscript of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto

The so-called “Brandenburg Concerts” languished in an archive until 1849 and weren’t published until 1850.

The third concerto is the briefest of the three, and features jaunty rhythms and enchanting calls and responses between instrument sections.

The video above is from an ensemble that seeks to replicate historic performance practice. You’ll notice that it sounds very different from Bach played by a full modern orchestra.

Partita for Violin in D-minor – ca. 1718-20

During this decade of instrumental experimentation, Bach wrote another set of six pieces, this time for solo violin: three sonatas and three partitas, combined into a larger work known as the six sonatas and partitas for solo violin.

The second partita is in five movements, consisting of melancholy, stylized dances for solo violin.

The first four movements are only a few minutes long each, but the final movement is a massive fifteen-minute-long piece in which Bach bares his very soul. It’s known as the Chaconne. (It starts at 15:09 in the video above.) Over the years, this piece has become one of the most important in the entire classical violin repertoire.

What’s the story behind this bizarrely proportioned, intensely emotional piece? Historians can’t know for sure, but we do know that in July 1720, Bach’s wife died suddenly while Bach was traveling for work.

It has been theorized that this work for lonely solo violin might have been his way of processing his grief. It’s unclear if it was ever performed in Bach’s lifetime, or even if he expected it to be.

Cello Suite No. 1 – ca. 1720

Around the same time, Bach wrote six suites for solo cello. (If you couldn’t tell already, he had a fascination with the number six!)

The first movement of the first suite has entered the pop culture lexicon, having been used in countless films and commercials. It is one of the most famous pieces of classical music ever written.

The Well-Tempered Clavier – 1722

In Western musical notation, there are twelve “major” keys and twelve “minor” keys.

This is an oversimplification, but during Bach’s lifetime, there were disagreements in the musical community about what kind of tuning system musicians should use.

One tuning method kept notes more in-tune but required re-tuning an instrument to move in between keys.

Another tuning method resulted in instruments that were slightly less in-tune but did not require tuning to go between keys. The latter was known as a “well-tempered” tuning system.

This collection of works featured two works in every key, so forty-eight pieces in all. It contributed to the important conversation about tuning systems, and also scratched Bach’s ever-present itch to write technically challenging pieces.

Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach – ca 1722-1725

In 1721, a year after the sudden death of his first wife, Bach remarried a woman named Anna Magdalena, who was almost half his age. She was a very talented singer, and she helped him with his work and took part in domestic family music-making as their many kids grew up and trained to join the family music business.

The Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach is a snapshot of the Bachs’ domestic life from this time. It contains a variety of charming, easier pieces that, even though they weren’t meant for public consumption, have become some of Bach’s most famous. Bach’s large family was a vitally important part of his life, and it’s important to keep it in mind when learning about his music.

St. John Passion – 1724

In 1723, a newly remarried Bach was appointed director of church music in Leipzig. But his duties extended beyond that: not only did he have to provide music for four churches, but he also had to teach at the famous St. Thomas School, which had first been founded in 1212.

He needed to make a good impression. So for the Easter season – the most liturgically important holiday in the Christian calendar – he composed the St. John’s Passion, which set passages from the book of John to music for choir, solo voices, and accompanying instruments. Altogether, the piece lasts for roughly two hours.

This Passion has occasionally been labeled anti-Semitic. Many scholars, musicians, and listeners have engaged with the topic of prejudice in both the Gospel of John and Bach’s setting of it, especially given the stew of anti-Semitism that was boiling in Bach’s time and homeland during his lifetime.

It’s important to have these kinds of conversations, because it’s a slippery slope to music being used to elucidate, or at least in some way endorse, hurtful or harmful political positions.

Double Concerto for Two Violins – ca 1730

Bach didn’t write a lot of solely instrumental music while he was working in Leipzig, but around 1730, he did somehow find time to curate a concert series.

He wrote this concerto for two violins for that series. It has since been affectionately nicknamed “the Bach double” among violinists.

The middle slow movement is the most famous part of the concerto – and one of the most famous pieces of classical music, period! It starts at 3:51 in the video above.

Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major – ca 1731

Between 1724 and 1731, Bach wrote a series of four orchestral suites. The third dates from later in that time period. It became his most popular, especially after it was championed in the nineteenth century by Romantic era composer Felix Mendelssohn.

This piece includes a movement that came to be known as Air on the G-string, which is a fixture at weddings today. It starts at 6:15 in the video above.

Goldberg Variations – 1741

We don’t know exactly why Bach wrote this piece, but a famous legend has sprung up around it. Supposedly, Bach was hired by an insomniac count to write music that would relax him and hopefully send him to sleep. The count’s harpsichordist tasked with this performance was a man named Goldberg, hence the name of the piece.

Whether that story is true or not, we do know that Bach loved a technical challenge. He took an initial theme and wrote thirty variations on it.

Today, this piece is usually played on piano instead of harpsichord, but the performance above is on harpsichord. If you’d prefer a piano version, here’s one of those.

Which version do you like better? Remember, there are lots of styles of Bach recordings out there, so if one doesn’t impress you, check out more!

Mass in B-minor – 1749

By 1749, Bach’s health was declining and he was losing his sight. At the same time, he finished writing this massive collection of church music that became known as the Mass in B-minor. It takes about two hours to perform.

We don’t know exactly why Bach took this massive project on at a time when it seemed clear the end of his life was likely nearing. He never even witnessed the entirety of the work played.

It was revived in the nineteenth century, and is still a part of the repertoire today.

Musicologist Alberto Basso wrote of it:

The Mass in B minor is the consecration of a whole life: started in 1733 for “diplomatic” reasons, it was finished in the very last years of Bach’s life, when he had already gone blind. This monumental work is a synthesis of every stylistic and technical contribution the Cantor of Leipzig made to music.

Conclusion

Bach wrote so much music, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. But these ten pieces span the gamut of his life and work, and hopefully give you a sense of whether his music is something you want to keep delving into.

The glorious thing about Bach is that there’s so much music, and so many performances, that a seasoned listener will always have as much to learn as a beginner.

So don’t be intimidated: find some Bach that moves you, and listen to it! Your life will be richer for it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter