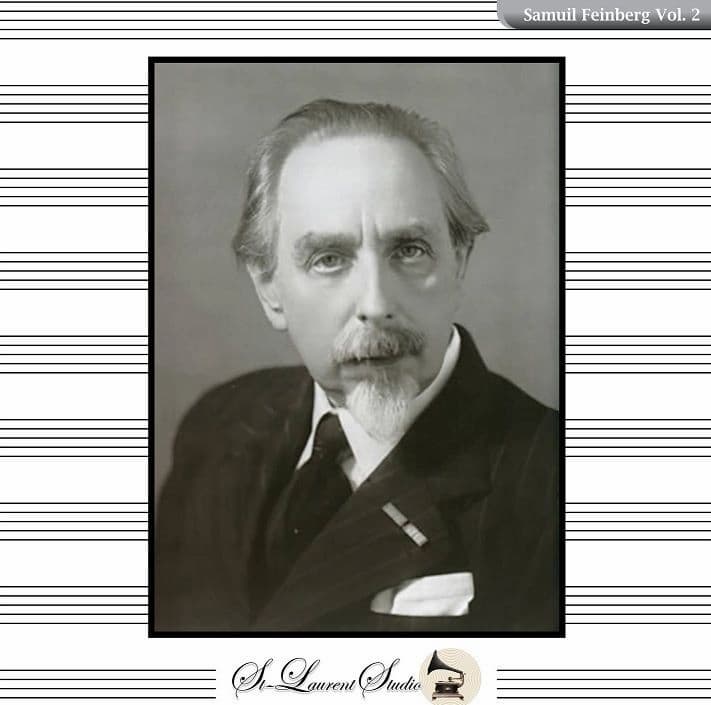

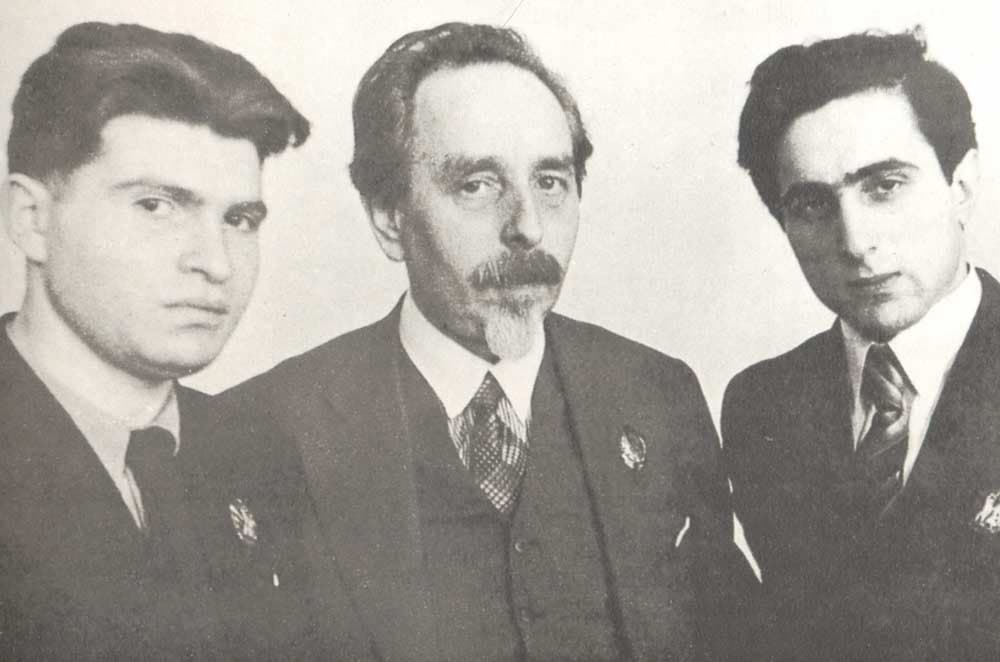

For a good many commentators, the Ukrainian city of Odessa is the “cradle of Russian pianism.” The unique blend of Russian, Yiddish, and Ukrainian cultures has given birth to pianists like Benno Moiseiwitsch, Vladimir de Pachmann, Shura Cherkassky, Emil Gilels, Maria Grinberg, Simon Barere, Leo Podolsky, and Yakov Zak. And we must add Samuil Feinberg, born on 26 May 1890, to that list.

Samuil Feinberg

Unlike Sviatoslav Richter who was not born in Odessa but studied there, Feinberg was born in Odessa but his parents moved to Moscow in 1894. Feinberg displayed an incredible musical aptitude from an early age, playing the piano by ear and improvising until the age of ten. During his early years, he did take a few lessons from Sofia Abramova Gourevich, and between the ages of 10 and 14 he studied with A.F. Jensen. Concurrently, Feinberg was taking private lessons in composition with Nikolai Zhilyaev, who was a very close friend of Scriabin. When Feinberg played a Scriabin Sonata for the composer, Scriabin “exclaimed that he had never heard such a convincing performance of his work.”

Samuil Feinberg Plays Scriabin’s Sonata No. 2 in G-sharp minor, Op. 19

By 1904, Feinberg was studying piano with the highly esteemed Soviet and Russian pianist, teacher, and composer Alexander Goldenweiser. Goldenweiser had studied piano with Pavel Pabst and composition in the class of Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov. Additional teachers included Anton Arensky and Sergei Taneyev.

The young Samuil Feinberg

In the event, for his graduation recital Feinberg prepared all forty-eight preludes and fugues from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, César Franck’s Prélude, Choral et Fugue, as well as music by Handel, Mozart and Chopin, Scriabin’s Sonata No. 4 Op. 30, and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 Op. 30. He immediately embarked on a pianistic career, which included two tours of Germany before the beginning of World War I. And let’s not forget that Feinberg was the first Russian pianist to perform the complete Well-Tempered Clavier in public in 1914. As such, it is utterly incomprehensible that Feinberg was conscripted into the Russian army and sent to the Polish front. Luckily, one might say, he contracted typhus and returned to Moscow for the remainder of the war.

Samuil Feinberg Plays Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 30, Op. 109

Feinberg’s musical lineage can be traced back all the way to Beethoven, and the two main pillars of piano tradition at the Moscow Conservatory during Feinberg’s time were Goldenweiser and Neuhaus. Feinberg became Head of the Piano Department at the Moscow Conservatory in 1922, and in 1927 once again performed throughout Germany. He premiered music by Scriabin, Stanchinsky, Myaskovsky, Prokofiev, Polovinkin, Goedicke and Katuar (Catoire), as well as his own compositions.

Samuil Feinberg’s recording of Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier

He acquired a reputation as a pianist of unmatched stamina, and the Russian pianist Alexander Brosovich wrote in his diary in 1926. “The phenomenal gift of Feinberg never ceases to amaze me. His mental organization and technical skills are really phenomenal… Feinberg plays like a devil… His fabulous talent strikes me fresh each time, as musically his brain works significantly better than mine, and I always have the feeling that I am far behind him.” And Prokofiev commented on his yet 5th yet unperformed sonata, “if Feinberg plays it, success can be taken for granted.”

Robert Schumann: Waldscenen, Op. 82 (Samuil Feinberg, piano)

A scholar writes, “Feinberg’s Scriabin playing is not to be missed, so improvisationally beguiling, with fluttering pedals purring and limpid, its incisive inner details somehow make for structural pillars. Reckless, languorous, erotic, Feinberg is driven by ecstasy, and the devil takes due notice.” And Mark Pakman added, “He infused every piece with a principal idea and character. Feinberg often accumulated enormous intensity in the very beginning of a musical phrase and then gradually let it subside. His timing was remarkable.”

Three pianists from Odessa: (from left to right) Emil Gilels, Samuil Feinberg and Yakov Zak in 1938

Feinberg had the ability to create remarkable amounts of tonal varieties, timbres and effects from the piano, and he consistently projected a clear layering of voices. Most expressive was his bel canto like singing tone, “an unparalleled legato line, improvisational freedom and sheer virtuosity when needed.” As a scholar writes, “Feinberg was an intellectual, sophisticated and highly educated man whose interests and knowledge went far beyond music and piano playing. He expressed himself in the most lucid, perceptive and clear-cut way.” And the same could be said for his style of playing, “as everything was completely considered and thought through.” For some critics, Feinberg is “without doubt, one of the greatest of Russian, if not all, pianists.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter