Classical music has a reputation for being altogether too serious. It’s an often-repeated cliché based on the great fear of being locked in a concert hall for several hours without the use of mobile phones. Granted, classical composers didn’t make it all that easy on audiences by giving pieces rather bland and generic titles. There is yet another “Symphony No. 64 in F major,” or a “Sonata for piano and violin No. 3.” Nothing, it turns out, is as threatening as the anticipation of having to sit around without knowing what is going on or what is being expressed. But once you dig below the seemingly austere surface of classical music, you’ll find that even the most highly esteemed composers are prone to occasional attacks of humor.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Leck mich im Arsch” (Kiss my ass), K. 231

Have fun with Mozart!

I started a little search, and here are 10 of the most hilarious titles in classical music, starting with Mozart’s famous canon “Kiss my ass.” It was probably written as a party piece, and the text was later sanitized by publishers, but Mozart’s hilarious original message is unmistakable.

Erik Satie: Embryons desséchés (Desiccated embryos)

Erik Satie: Embryons desséchés (Desiccated embryos)

It didn’t take me long to find the king of hilarious titles in Erik Satie (1866-1925). He had nothing but contempt for tradition, a deliciously rye humor, and complete loyalty to the absurd. He invented so-called furniture music, a kind of background not to be listened to consciously. A close friend and collaborator wrote, “Satie is extraordinary. He is a mischievous and cunning old artist. At least, that’s how he thinks of himself.” His irreverence for convention and eccentricity is probably best demonstrated in his short piano pieces with evocative titles like “Three Boneless Preludes for a Dog,” or “Embryons desséchés” (Desiccated embryos). While the title is hilarious, the three little movements lasting about two or three minutes to play, have additional subtitles. The first is called “Desiccated embryo of a Holothurian,” basically a sea cucumber, a creature without eyes. The second features the “Desiccated embryo of an Edriophthalma,” a crustacean with immobile eyes, and the concluding movement carries the title “Desiccated embryo of a Podophthalma,” a stalk-eyed crustacean like a crab or lobster.

And to make sure the pianist knows how to approach these morsels of irreverence, Satie tells them to play it “like a nightingale with toothache.”

Erik Satie: Embryons desseches (Klára Körmendi, piano)

Paul Hindemith: Overture to the Flying Dutchman

Paul Hindemith: Overture to the Flying Dutchman

I am not sure you have ever heard of the German composer, music theorist violist, and conductor Paul Hindemith (1895-1963). But if you have, you probably know that he was a major advocate of a musical style called “New Objectivity,” and “Music for Use,” which advocated composition intended to have a social or political purpose. You might also know that he wrote in a complex modernist polyphonic style. You might not know, however, that Hindemith had a wicked sense of humor. In 1925, Hindemith composed a string quartet with the title “Overture to the Flying Dutchman,” making an obvious reference to the opera by Richard Wagner. Nothing hilarious about the title so far, but you only need to read the subtitle to understand this musical parody. The Overture is supposed to be “sight-read by a bad Spa Orchestra at 7 in the morning by the well.” Wagner’s music is completely mangled and includes errors in the playing of the tune, rhythmic imprecations, and all kinds of interpretative deficiencies. A critic writes, “it is not clear whether Hindemith is satirizing Wagner, incompetent performers, ostentatiously dissonant composers, or the introduction of popular elements into serious music.” Whatever the case may be, it is decidedly hilarious.

George Bizet: Le docteur Miracle, “Quatuor de l’omelette”

Georges Bizet’s opretta Doctor Miracle

Georges Bizet (1838-1875) composed his operetta Doctor Miracle when he was barely 18 years old for a competition organized by Jacques Offenbach. He did share the first prize with Charles Lecocq, and the premiere sounded on 9 April 1857 at Théâtre des Bouffes Parisiens in Paris. The story is set in Padua, and the major and his wife Véronique are woken by a noisy advertising campaign outside their house, proclaiming the talents of Doctor Miracle. Doctor Miracle is actually a young military officer who has fallen in love with the major’s daughter Laurette. To gain access to the house, Silvio disguises himself as the servant Pasquin, and he boosts about his cooking talents. The mayor is delighted, and since it is time for breakfast, he invites Pasquin to prepare an omelet. This brings us to the hilariously funny “Omelette Quartet,” with Pasquin preparing the dish and everybody singing its praises. But once they actually taste it, they all start to choke, as it is disgusting. The mayor and his wife rush from the house to rinse their mouths, which gives Laurette and Silvio time to sing a tender love duet.

Georges Bizet: Le docteur Miracle – Scene 7: Quatuor de l’omelette: Voici l’omelette! (Jerome Billy, tenor; Isabelle Druet, mezzo-soprano; Pierre-Yves Pruvot, baritone; Marie-Benedicte Souquet, soprano; Orchestre Lyrique de Region Avignon Provence; Samuel Jean, cond.)

Franz Reizenstein: Concerto populare, “A piano concerto to end all piano concertos”

Franz Reizenstein

Have you ever heard of the “Piano concerto to end all piano concertos?” That’s the subtitle of the “Concerto Popolare” by Franz Reizenstein (1911-1968), a student of Paul Hindemith. The premise of the composition is fairly simple. The orchestra believes that they are playing Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, while the pianist is convinced that the Piano Concerto by Grieg is on the program. It all turns into a funny battle between musical forces, with both sides trying to figure out what is actually going on. Becoming increasingly unsure, other themes creep into the compositions. You will immediately recognize the Rhapsody in Blue, the Warsaw Concerto and the song “Roll out the Barrel.” The Australian pianist Eileen Joyce was invited to perform the premiere, but she declined. As such, the first performance featured the renowned actress Yvonne Arnaud as the soloist. If this kind of parody is to your liking, you might also want to have a listen to Reizenstein’s “Let’s Fake an Opera,” in which the libretto consists of “ridiculously juxtaposed excerpts from more than forty operas.” The work was called “an insane collage of opera plots and themes.”

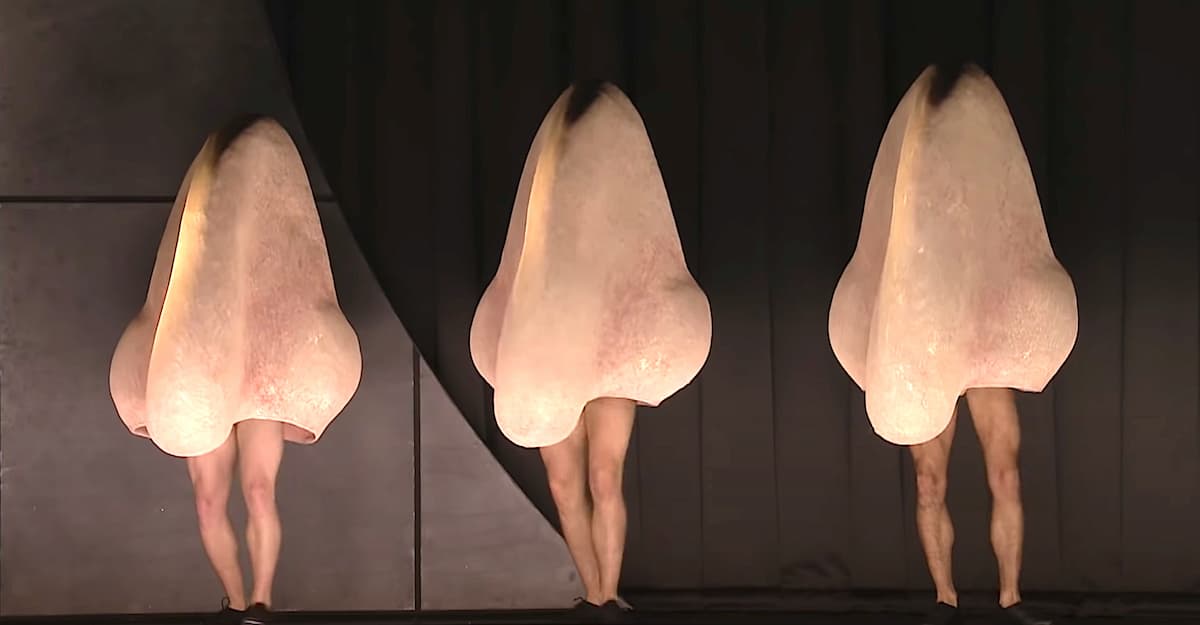

Dmitri Shostakovich: “Tap-dancing Noses”

Tap-dancing Noses

Without doubt, my favorite and one of the most hilariously funny titles for an opera comes courtesy of the Russian playwright Nikolai Gogol and composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975). It is called “The Nose” and tells the story of Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov who gets a shave in Yakovlevich’s barbershop. The very next morning, the barber discovers a human nose in a freshly baked loaf of bread, and when he throws the nose into the Neva River, he is observed by a police officer and taken in for questioning.

Kovalyov, meanwhile, awakes and discovers that his nose has disappeared. He rushes off to search for it, and he finds the nose—now the size of a human being—sitting at prayer in the cathedral. He demands that the nose return to its proper size and place, but the nose refuses and escapes. The police are taking up the chase and are looking for the nose, and it is finally arrested at a train station and beaten back to its normal size. However, it still refuses to be reattached to Kovalyov’s face, who has a dreadful nightmare. As he awakes one morning, the nose is finally back in its rightful place and position. How is that for a hilarious title and story?

Lord Berners: “Funeral March for a Rich Aunt”

Lord Berners in 1935

Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson (1883-1950) became the 14th holder of the Berners Barony, inheriting the title, property, and money from an uncle. Forthwith known as Lord Berners, he was notorious for his eccentricity, “dying pigeons at his house in vibrant colors.” He also kept paper flowers in the garden, and his house was adorned with joke notices. On the top of the stairs was a sign “No dogs admitted,” and “Prepare to meet their God” painted inside a wardrobe. According to a houseguest, he used to paint his favorite horse, and put Woolworth pearl necklaces around his dogs called “Heber-Percy” and “Pansy Lamb.” He was actually visited by Igor Stravinsky, Salvador Dali, H.G. Wells, and Tom Driberg. In his Rolls-Royce automobile he kept a small clavichord keyboard, “which could be stored beneath the front seat.” Lord Berners was also a composer who declared, “I would have been a better composer if I had accepted fewer lunch invitations.” By now, you might not be surprised that Lord Berners came up with a number of funny titles, including “Funeral March for a Rich Aunt.” This piano miniature isn’t remotely appropriate for a funeral as the composer is giddily counting the money from his inheritance.

Lord Berners: 3 Petites Marches funèbres (3 Little Funeral Marches) – No. 3. Pour une tante à héritage (For a Wealthy Aunt) (Len Vorster, piano)

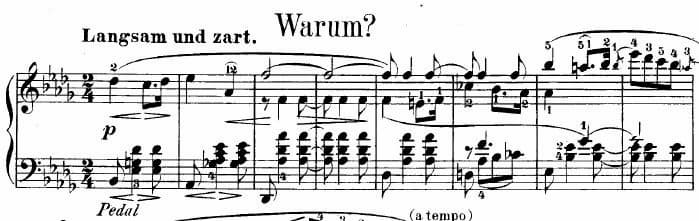

Robert Schumann: Fantasiestücke, Op. 12, Nr. 3 “Why”

Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestücke, Op. 12 No. 3

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) had a distinct passion for literature and poetry. Always deeply emotional, Schumann “viewed music as a way of expressing the inner working of his constantly shifting mind.” At once dreamy or agitated, he tried to find ways of fusing literary and musical imagery, and in the process came up with some rather evocative titles for his creations. We find such titles as “Scenes from Childhood,” “Butterflies,” “Fairy Tales,” titles that are supposedly meant to draw the listener into his subtle world of color, mood, texture, and poetic allusion. My favorite Schumann title comes from his Fantasiestücke Op. 12, a set of eight pieces for piano written in 1837. The overall title was inspired by various writings by E. T. A. Hoffmann, and the third piece in the series is simply entitled “Why.” The piece starts with a gentle musical question and ends with an inconclusive answer. Well, why not?

Robert Schumann: Fantasiestücke, Op. 12 – III. Warum? (Daniela Ruso, piano)

Luigi Russolo: “Serenata per intonarumori” (Sound box Serenade)

Luigi Russolo, ca. 1916

What could be nicer than listening to a serenade? Such calm and light pieces of music written for special occasions include the famous “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” and other works by that title by Brahms, Beethoven, Berlioz, Schubert, Sibelius, and others. I am sure that listeners were in high anticipation of Luigi Russolo’s (1885-1947) “Serenata per intonarumori,” roughly translated as “Serenade for sound boxes.” Russolo actually built 27 varieties of these “sound boxes,” which produced a range of noises when operated by a handle. The instruments were completely acoustic, not electronic, and featured various types of internal construction to create different types of noise music. Insiders had probably already read Russolo’s manifesto The Art of Noises of 1913, which is frequently regarded as one of the first noise music treatises. Russolo proudly proclaimed, “that the industrial revolution had given modern men a greater capacity to appreciate more complex sounds.” Sufficed to say, his “Sound box Serenade” was not a hit. When it was performed at the “Gran Concerto Futuristico” in 1917, audiences resorted to riotous violence to voice their disapproval. None of Russolo’s original “sound boxes” have survived, but replicas have since been built and performed.

P.D.Q. Bach: The Short-Tempered Clavier

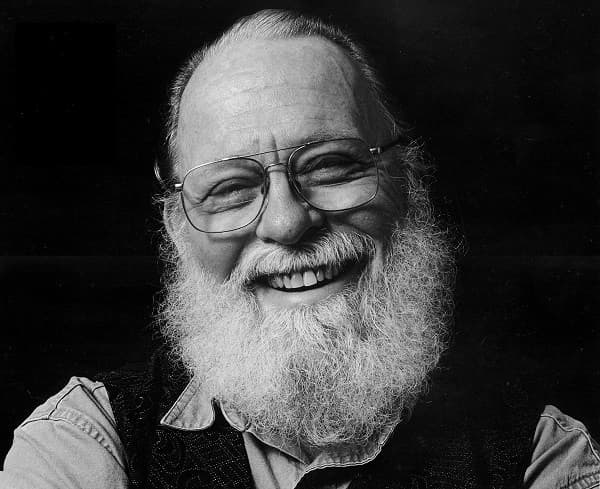

Peter Schickele, widely known as P.D.Q. Bach

Parodies have been part of classical music ever since its very beginnings. And classical music is still subject to hilarious skits, courtesy, among others, by Professor Peter Schickele, an American composer, musical educator, and parodist. Schickele is probably better known as the musical persona P.D.Q. Bach. In this fictional biography, he is described “as Johann Sebastian’s last and least offspring.” The Bach family wanted nothing to do with him, and called him “a pimple on the face of music,” “the most dangerous musician since Nero,” and “the worst musician ever to have trod organ pedals.” P.D.Q claimed that his father never gave him training in music, but taking advantage of his famous name, he started writing music divided into three creative periods. “The Initial Plunge,” “The Soused Period,” and finally “Contrition.” P.D.Q freely stole music from Haydn and Mozart, and as a great visionary, he anticipated the music of Beethoven and Jazz, and also the mannerisms of the emerging virtuoso culture. One of the funniest PDQ Bach creations, sporting yet another hilarious title is “The Short-Tempered Clavier.” It is a collection of preludes and fugues in all the major and minor keys, “except for the really hard ones.” You will hear a fugue on chopsticks and the chimes of Big Ben, among countless others. How many tunes and allusions can you recognize?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

PS to my previous comment: What about Chabrier and Messager’s terrific four hand piano version of the Ring of the Nibelung? Fantasy en from de quadrille sur les themes favors de L”Anneau de Nibelung” de Richard Wagner????FUN!!!!!! to play and hear.

Wry humor, Methinks, for Satie