“Memoirs of an Amnesiac”

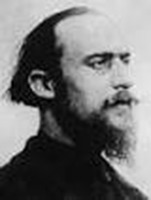

When eccentricity and classical music are used in the same sentence, Erik Satie (1866-1925) immediately comes to mind. Irreverent, disrespectful, contemptuous of tradition, forcefully direct and brutally honest, Satie famously wrote underneath his self-portrait, “I have come into the world very young into an era very old.” Actually, Alfred Erik Leslie Satie was born in Honfleur, Normandy in 1866. He came from a comfortable bourgeois background and showed some early interest in music. After taking piano lessons from a local church organist, he entered into the Parisian Conservatoire by 1879 but was quickly labelled “the laziest student in the world.” Georges Mathias, his professor of piano at the Conservatoire described Satie’s technique as “insignificant and laborious, and entirely worthless.” Satie was unceremoniously expelled after a couple of years, but at the petition of his father, readmitted soon thereafter. Soon he was expelled again, and counseled to take up military service. That career was also short-lived, as he deliberately infecting himself with bronchitis to escape the army. Penniless, but full of youthful exuberance and eccentricity he took up lodgings in Montmartre in 1886, rubbing shoulders with the artistic and literary elite. And, he also published his first works.

When eccentricity and classical music are used in the same sentence, Erik Satie (1866-1925) immediately comes to mind. Irreverent, disrespectful, contemptuous of tradition, forcefully direct and brutally honest, Satie famously wrote underneath his self-portrait, “I have come into the world very young into an era very old.” Actually, Alfred Erik Leslie Satie was born in Honfleur, Normandy in 1866. He came from a comfortable bourgeois background and showed some early interest in music. After taking piano lessons from a local church organist, he entered into the Parisian Conservatoire by 1879 but was quickly labelled “the laziest student in the world.” Georges Mathias, his professor of piano at the Conservatoire described Satie’s technique as “insignificant and laborious, and entirely worthless.” Satie was unceremoniously expelled after a couple of years, but at the petition of his father, readmitted soon thereafter. Soon he was expelled again, and counseled to take up military service. That career was also short-lived, as he deliberately infecting himself with bronchitis to escape the army. Penniless, but full of youthful exuberance and eccentricity he took up lodgings in Montmartre in 1886, rubbing shoulders with the artistic and literary elite. And, he also published his first works.

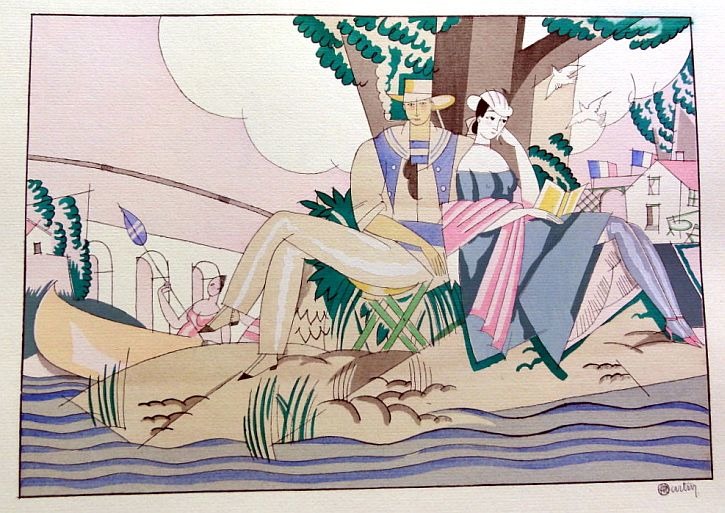

For over a decade, Satie immersed himself into the bohemian world of the Parisian café-concert and the music hall. Playing the piano and composing songs, Satie worked in an environment that reeked of “tobacco, spirits, beer, and gas all mingled together. On the stage, skimpily clad females with little voices sang suggestive songs of an inferior subject-matter.” From his one-room apartment, which contained two pianos stacked on top of each other, he exercised a remarkable influence over a younger generation of composers. Claude Debussy described Satie as “a gentle medieval musician lost in this century,” yet his mastery of the musical understatement attracted and greatly influenced Francis Poulenc, Darius Milhaud and John Cage. His association with a number of philosophical and religious organizations, most notably the Rosicrucian Brotherhood, developed his interest in mystical religion and Gothic art, and initiated a long search for artistic direction.

One such direction was his mature student enrollment at the “Schola Contorum” in October 1905. This conservative and controversial music school was run by Vincent d’Indy, and Satie gained a diploma in counterpoint, and one in composition and orchestration. As a result, Satie’s music took on a more academic quality, while still retaining its sense of irony. When Maurice Ravel performed some of his earliest works in 1911, Satie was suddenly seen as a harmonic forerunner of Impressionism. Publishers eagerly snatched up a number of recent works, and the celebrated pianist Viñes became an enthusiastic promoter of his cause. World War I interrupted the flow of concerts and publications, but he was supremely lucky that his music attracted the attention of the French playwright, designer and filmmaker Jean Cocteau. Cocteau was incredibly well connected in Parisian artistic circles, and he paved the way for the extraordinary collaboration between Diaghilev-Massine-Picasso-Satie in the ballet Parade of 1917.

After this succès de scandale and his involvement with “Les Six”—a group of avant garde French composers working in Montparnasse—Satie’s career centered around the theatre, and he could afford to write mostly on commission. A commission from the Princesse de Polignac resulted in his masterpiece Socarte, a work that greatly impressed Igor Stravinsky. After 1920, Satie increasingly focused on his journalistic career, joined the Communist party and became involved in the Dada movement. His ballets Mercure and Relâche provoked first night scandals, and he also composed music for the surrealist film Entr’acte. Decades of heavy drinking finally caught up with Satie in February 1925, and he was hospitalized due to cirrhosis of the liver. In his final days, he received the last rites of the Catholic Church, and died 90 years ago, on 1 July 1925. Satie was decidedly rebellious, ruthless, scathing and always proudly independent. A keen observer of life, he artistically encoded his impressions with a thick layer of satire and parody that nevertheless hid a philosophical and deeply spiritual side. Satie was an iconoclast composer, “a man of ideas who looked constantly towards the future.”

Erik Satie: Relâche, Act 1 Cinema

You May Also Like

-

Erik Satie: “Like a nightingale with toothache” Like many composers past and present, Erik Satie was in constant financial troubles. To escape his creditors he frequently changed his lodgings, ending up in a tiny room at 6 rue Cortot in the spring of 1890.

Erik Satie: “Like a nightingale with toothache” Like many composers past and present, Erik Satie was in constant financial troubles. To escape his creditors he frequently changed his lodgings, ending up in a tiny room at 6 rue Cortot in the spring of 1890. -

“Before I compose a piece, I walk around it several times” For Erik Satie, dance, theatre and cabaret music run as virtually continuous threads throughout his life.

“Before I compose a piece, I walk around it several times” For Erik Satie, dance, theatre and cabaret music run as virtually continuous threads throughout his life. - Boneless Preludes and Greetings to the Goat

Erik Satie and Suzanne Valadon Recently, I came across a composition entitled Three Boneless Preludes for a Dog... -

Georges Braque and Erik Satie – A Musical Friendship Violins, guitars, mandolins, music sheets and references to classical composers are very much part of Braque’s oeuvre...

Georges Braque and Erik Satie – A Musical Friendship Violins, guitars, mandolins, music sheets and references to classical composers are very much part of Braque’s oeuvre...

More Composers

- The 100th Anniversary of Erik Satie

Celebrating a Musical Maverick Explore the French composer's revolutionary simplicity -

Georges Bizet Honouring the Legacy of a Musical Genius

Georges Bizet Honouring the Legacy of a Musical Genius -

Antonio Salieri Salieri at 200: Celebrating Five Operatic Gems

Antonio Salieri Salieri at 200: Celebrating Five Operatic Gems -

George Frideric Handel Did you know Handel once fought a duel with fellow composer Johann Mattheson?

George Frideric Handel Did you know Handel once fought a duel with fellow composer Johann Mattheson?