“Music is the most romantic of all the arts for its sole subject is the infinite”

E. T. A. Hoffmann

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776-1822), better known by his pen name E. T. A. Hoffmann, was possibly the most original and influential fiction writer of the German Romantic era. “His fantastic tales epitomize the Romantic fascination with the supernatural and the expressively distorted or exaggerated,” and they decisively influenced 19th-century literature and the arts. Hoffmann made considerable contributions to our understanding of the emergence of scientific knowledge in the early part of the nineteenth century, and “to the conflict between science and magic.” Hoffmann also set new literary standards for writing about music and wrote forceful reviews of the music of his time. His reviews of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony and other important works encouraged subsequent writers to consider music as the most Romantic of all the arts. Hoffman always strove for artistic polymathy, and he regarded his work as a composer as significant, a view not necessarily shared by his contemporaries. For Hoffmann, artistic pursuits always spilled over into one another, so it is not surprising that he was also a gifted artist and author of some excellent sketches and caricatures.

E. T. A. Hoffmann: Piano Trio in E Major, AV 52 (Trio Bamberg)

A self-caricature by E. T. A. Hoffmann

Hoffmann was born in Königsberg, presently Kaliningrad, to a family of jurists. His uncle Otto Doerffer, “an unimaginative, mechanical and strict disciplinarian,” directed his initial education. He was compelled to study law, but concurrently studied painting and music. He was taught piano by Carl Gottlieb Richter (1728–1809), thoroughbass and counterpoint by the Königsberg organist Christian Wilhelm Podbielski (1740–92), and violin by the choirmaster Christian Otto Gladau. Hoffmann completed his law studies in 1795 and found employment as a clerk in Berlin. He enthusiastically attended performances of Italian opera and took composition lessons from J.F. Reichardt, with his earliest compositions dating from this period. With typical panache, he sent his first operetta “The Mask” to Queen Luise of Prussia. He was advised to write to the director of the Royal Theatre, but before he was able to proceed he passed his final law examination and was appointed assistant judge at the high court in Posen, presently Poznań.

E. T. A. Hoffmann: Keyboard Sonata in C-sharp minor (Wolfgang Brunner, fortepiano)

E. T. A. Hoffmann: “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King.” © University of Oldenburg

Hoffmann got himself into trouble for drawing caricatures of military authorities in the Posen garrison, and was sent into exile in southern Prussia. Unable to organize public performances of his music, Hoffmann tried to have his compositions printed. He submitted a number of piano pieces to the publishers Nägeli and Schott, but all were rejected. He even entered a literary competition but his comedy “The Prize” which took as its subject the competition itself brought him no prize money, only the judges’ commendation. However, he did manage to get himself transferred to Warsaw in 1804. Hoffmann the musician made a completely fresh start, and after only a year he had an opera successfully staged, completed the D-minor Mass and had a piano sonata published in a Polish music magazine. Hoffmann busied himself as a conductor, a pianist, and a singer. When Napoleon entered Warsaw, Hoffmann refused to sign a declaration of submission and take an oath of allegiance. He was expelled and drifted to Berlin. Eventually he took the post of music director at the theatre in Bamberg, and began work as music critic for the “Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung” in Leipzig.

E. T. A. Hoffmann: Symphony in E-flat Major (Akademie Kölner; Michael Alexander Willens, cond.)

E. T. A. Hoffmann: Johannes Kreisler

Hoffmann’s literary breakthrough came in 1809 with the publication of “Ritter Gluck,” the story about a man who believes that he had met the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck more than twenty years after the latter’s death. “The mastering of unfulfilled passion remained Hoffmann’s poetic mission to the end of his life; he himself hinted at the close connection between his hopeless love for his young pupil Julia Mark, the crucial experience of his Bamberg years, and the impetus of his literary production.” And while the “Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier,” “Johannes Kreisler,” and “Don Juan” became overnight literary sensations, Hoffmann continued to pursue his musical career.

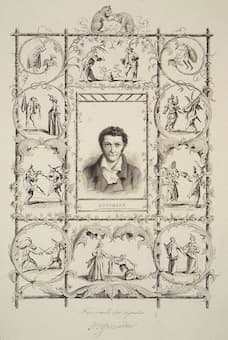

The frontispiece of an 1841 edition of Hoffmann’s collected works © Bavarian State Library

His most important work, the opera Undine premiered in 1816. In his review, Carl Maria von Weber “praised the swift pace and forward-pressing dramatic action and had kind words for Hoffmann’s restraint in avoiding excessive and inapt melodic decoration.” Sadly, after the opera’s 14th performance the Königliches Schauspielhaus in Berlin burned to the ground and Undine was never again staged during Hoffmann’s lifetime. Robert Schumann was Hoffmann’s most famous follower, and he claimed “Hoffmann was at the heart of his music, with the titles of some of his most famous compositions, including Fantasiestücke, Nachtstücke, and Kreisleriana amply proving his point. To be sure, Hoffmann’s personality and talents lent a “distinctive, if somewhat lurid, hue to Romanticism and influenced several generations of artists, writers and composers.” Fighting bureaucracy until the end, Hoffmann died 200 years ago, on 25 June 1822 of syphilis at the age of 46.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

E. T. A. Hoffmann: Undine – Act 1