Chamber music featuring the piano has always been popular. The reason is comparatively simple; similarly to a string quartet as a whole ensemble, the piano is a perfect unit in itself. It is also one of the reasons the musical genre of the piano quintet has its own special charm. It is certainly fascinating that the two main components both have autonomy and independence.

A noted performer considers the piano quintet “the perfect line-up in chamber music, since the two components have a wide spectrum of sonorities at their disposal, enabling them to bring out all the timbre qualities we know from chamber as well as orchestral music.”

From Schumann to Brahms and from Arensky to Zwilich, the piano quintet has been of great fascination to composers. It takes special technical and musical skills to successfully tame the possibilities offered by the entire grouping. By popular request, we decided to feature some delightful bonus repertoire for piano quintet.

Max Bruch: Piano Quintet in G minor

Max Bruch (1838-1920) is primarily known for his wonderful first violin concerto. However, over his long life, he published almost 100 works in all varieties of musical forms, from oratorio and cantatas to concertos and symphonies to songs. Bruch was primarily a conductor, and between 1880 and 1883, he was appointed Music Director to the Liverpool Philharmonic Society.

One of his close friends was a music lover by the name of Andrew Kurtz, who was head of a chemical factory and a member of the Philharmonic Society Committee. He was also an amateur pianist who hosted frequent salons for chamber music. As such, Bruch began a piano quintet for Kurtz in 1881, yet the work was only partially complete. Bruch finally finished it in 1888 after a desperate plea from his English friends: “we are all anxious for the completion of the work. We have been anticipating every week to receive the conclusion of the last movement.”

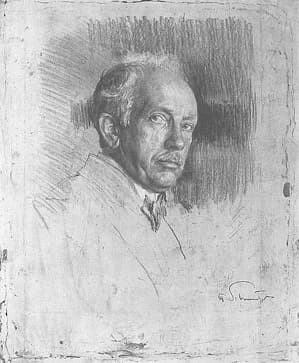

Max Bruch

Bruch tailored the work to the musical abilities of Kurtz and his associates and stayed away from complex technical demands. It unfolds in simply structured four movements, frequently sounding unison writing in the string above a chordal piano accompaniment. The slow movement shares the key with the slow movement of the famous violin concerto, and the “Scherzo” and “Trio” are full of lyricism worthy of Mendelssohn. It’s a thoroughly delightful work that should be played with much more regularity.

Anton Rubinstein: Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 99

Anton Rubinstein: Piano Quintet in G Minor, Op. 99 (Pihtipudas Kvintetti)

We have already met the exceptional pianist Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894) within the context of the piano trio. How good a pianist was Anton Rubinstein? When Liszt retired from the concert stage in 1847, Rubinstein took over from him as the most astonishing pianist of the day. For one, Rubinstein had a phenomenal technique and huge hands. In all, he published nearly 120 works, including five piano concertos.

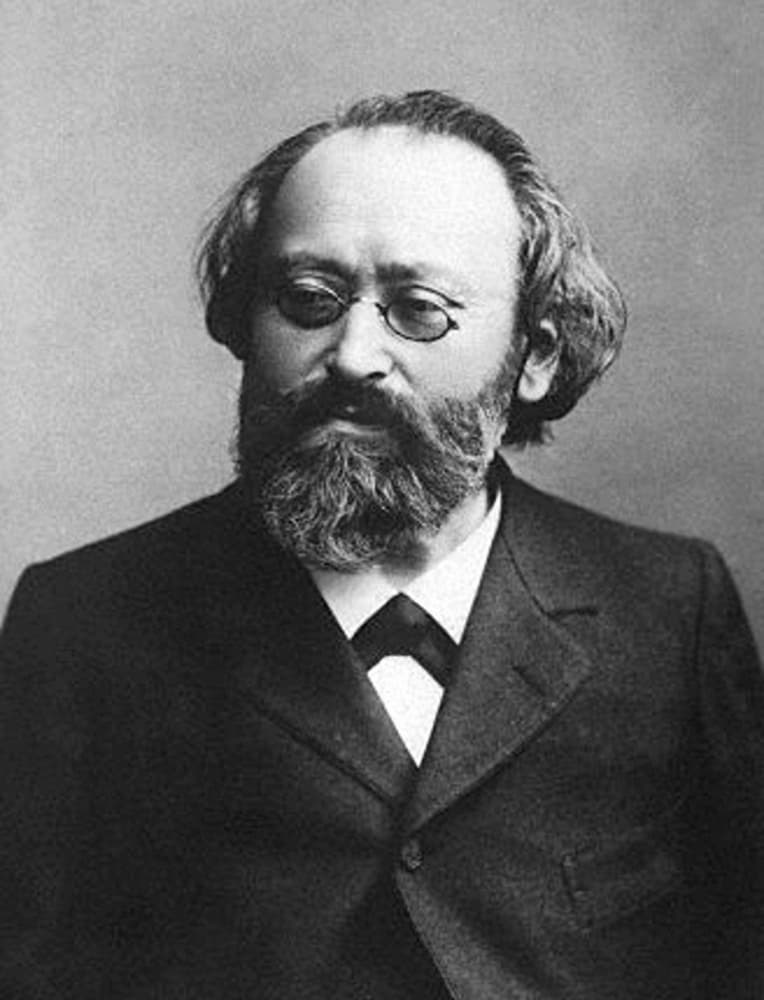

Portrait of Composer Anton Rubinstein by Michail Michailovich Yarowoy

As a composer, Rubinstein was most successful when the piano was involved. The Quintet for Piano and Strings, Op. 99 was written in 1876 and published two years later. Christopher Fifield writes, “the work displays great depth of thought and good craftmanship with a broad vein of melody supported by natural harmony. It is clearly a work of a pianist, the part calling for considerable virtuosity.”

Rubinstein provides a recitative-style introduction infused with piano flourishes as a lead-in for the “Allegro moderate.” The composer alternates chromatic harmony and homophonic string writing, and the rousing coda is preceded by another virtuosic cadenza for the piano. Full of charm and delicacy, “the Intermezzo” sounds like a dialogue between the solo piano and the string quartet. A number of variations sound at the core of the slow movement, and the exciting “Finale” is dominated by energetic rhythms and bubbling pianism.

Franz Berwald: Piano Quintet No. 2 in A Major

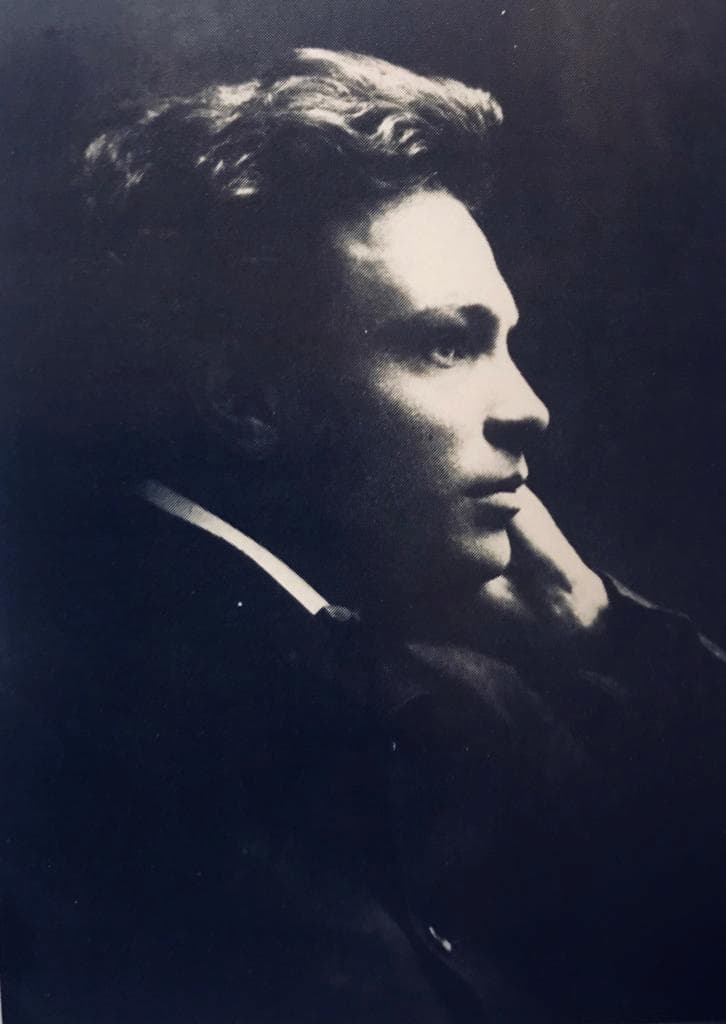

Franz Berwald

Franz Berwald: Piano Quintet No. 2 in A Major (Uppsala Chamber Soloists; Bengt-Åke Lundin, piano)

Today, we consider Franz Berwald (1796-1868) Sweden’s foremost composer of the nineteenth century, but he was really not appreciated during his lifetime. Berwald spent many years abroad, and he was warmly received. However, when he returned to Sweden for good in 1849, he had to manage a glassworks in northern Sweden to make a living. Since his larger works did not find favour with audiences, he concentrated almost completely on chamber music.

There was one more reason why Berwald became interested in chamber music, and her name was Hilde Thegerström. She went to study in Paris with Antoine Marmontel and with Franz Liszt in Weimar. Barely twenty, she soon came to be regarded as Sweden’s foremost pianist. And it was for Hilde Thegerström that Berwald composed his piano quintet as well as his piano concerto.

Hilde Thegerström

Berwald showed his C-minor quintet to Liszt and reported, “I have had the opportunity to hear my quintet played, straight from the score, by a true poetic master. No longer just a piano but a whole orchestra!” As a token of thanks, Berwald dedicated his A Major quintet to Liszt, and when it was published, Liszt sent a message to Berwald. “You express yourself with invention, skill, and agility; your developments and recapitulations are masterfully executed, and your style is both elegant and harmonically original.”

Frank Martin: Piano Quintet

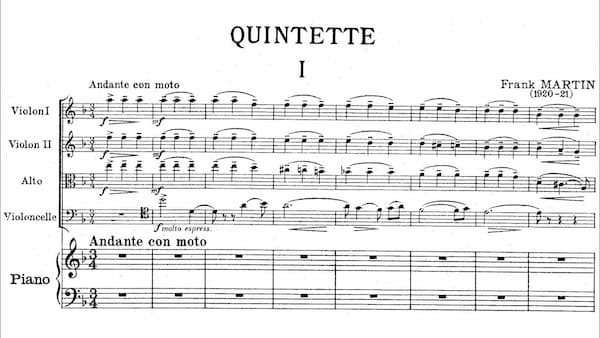

Frank Martin’s Piano Quintet

Frank Martin: Piano Quintet (Martin Klett, piano; Armida Quartet)

Frank Martin (1890-1974) once described the inadequacies of the keyboard as follows, “We only have two hands, and our ten fingers are not capable of exploiting all the possibilities.” I suppose Martin rather too closely compared the piano with the “intimate sonorities imaginable, and the dense amassment of sound we encounter in a symphony.”

Martin never studied music at the conservatory, but at the age of eleven, he heard J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, and this experience shaped his life. He ceaselessly studied Bach’s counterpoint and took composition lessons from Joseph Lauber, a student of Josef Gabriel Rheinberger. By 1914, Martin explored the modal harmonies of Debussy and Ravel, and his style, “neither tonal nor atonal, neither traditional nor avant-garde, is a fascinating one-off in the history of 20th-century music.”

The piano quintet is deeply rooted in Romanticism, brimming with passionate expressions. It was premiered in 1919, and it “stands out not only in terms of harmonic refinement but also for its elaborate contrapuntal interweaving of highly independent parts.” The opening movement, to quote an esteemed ensemble, “sounds like the St Matthew Passion married to Tango Passion.” Bach also appears to be the model for the slow movement, and Ravel informs much of the finely chiselled final movement.

Enrique Granados: Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 49

The music of Enrique Granados (1867-1916) reflects the cultural diversity that has continued to mark the various regions within Spain. He was a native of Catalonia, a province in northeastern Spain, and his patriotism to his native Spain is amply reflected in his musical production. Although Granados made Barcelona his base of operations, it was not Catalonian folk music but Castilian folk music that made itself directly felt in his music.

Granados certainly had high ambitions, as he writes, “I want to be in my country what Saint-Saëns and Brahms are in theirs.” His piano quintet Op. 49 was composed in 1894 and it immediately managed to seduce listeners with a great deal of grace and spontaneity. Already in the opening unison passages, we are treated to rhythmic elements that essentially define his writing. Just listen to the wonderful harmonic combinations and the firm control in handling counterpoint.

Enrique Granados in 1914

Granados skilfully divides the musical interest among the various instruments and at once creates an atmosphere of passion and intensity. According to an annotator, “the second movement is characterised by beauty, taste, and refinement, and the use of mutes creates a remote and bucolic sound.” Granados returns to clearly defined rhythms in the concluding movement, and it is easy to see that the piano quintet marked the beginning of his artistic maturity and national reputation.

George Enescu: Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. 29

The A-minor piano quintet, Op. 29 by George Enescu (1881-1955) is dedicated to the memory of his early patron Princess Elena Bibescu. An accomplished pianist, she had given much support to the composer during his year in Paris at the turn of the century. Early drafts of the work date back to the 1920s, but it was only completed between July 1943 and May 1944. The work was not performed in Enescu’s lifetime and was only premiered in 1964.

Richard Whitehouse writes, “In size and scope, it recalls the First String Quartet (1920) in its expansiveness and overall emotional sweep, exemplifying a potent expressive focus and textural finesse.” It was written in memory of his teacher Gabriel Fauré, and “marking the twentieth anniversary of his death, the music is akin to the older composer’s last chamber works in its refinement of mood, though not its intricate counterpoint.”

All three movements adopt conventional formal conventions in unexpected ways, as the themes are transformed from beginning to end. The opening “Allegro moderato” initially develops the two main themes with subtle contrasts in mood, while the “Vivace” sounds a more robust dance-like theme. Memories of the first movement return and combine with the energy of the second movement in the concluding “Con moto moderato.”

Ottorino Respighi: Piano Quintet in F minor

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) composed his piano quintet in F minor in 1902 after he returned to Bologna from his first trip to Russia. The composer wrote it for the Mugellini Quintet, a group founded by Bruno Mugellini. The quintet was part of a series of works when the composer was searching for a personal style “and was to draw his inspiration on more than one occasion from the Gregorian period.”

Ottorino Respighi, 1912

From the very beginning, the work seems to evoke Brahms, but Respighi quickly puts his own stylistic stamp onto the music. Given its forceful and dominant piano part, it actually sounds more like a piano concerto in spots, and it’s not surprising that he composed his Piano Concerto in A minor around the same time.

The opening “Allegro” provides a rich musical atmosphere steeped in romantic elements as it relies on robust architecture. This grand opening towers over the two following movements, including an “Andantino” of vaguely popular flavour. Actually, it sounds like a combination of Schumann’s piano polyphony and Dvorak’s quartet writing. The concluding “Vivacissimo” is a moto perpetuo in triplet, and it all ends with a swirling coda.

Dora Pejačević: Piano Quintet in B minor, Op. 40

Dora Pejačević: Piano Quintet in B minor, Op. 40 (Quatuor Sine Nomine; Oliver Triendl, piano)

Dora Pejačević (1885–1923) was born in Budapest but grew up in her ancestral Croatia. Her mother was a Hungarian countess, “a woman of great beauty who was a trained singer, played the piano and was a fine amateur painter.” She taught herself to play the piano, and her early compositions paved the way for her to study abroad. She attended the Croatian Music Institute in Zagreb and also took lessons in Dresden and in Munich. However, in musical terms, she was largely self-taught, “which is remarkable considering the inventiveness, rich brilliance and enduring quality of her compositions.”

Dora Pejačević

Her compositions follow a late Romantic idiom “enriched with Impressionist harmonies and lush orchestral colours.” In her music, Pejačević always strove to break free “from drawing-room mannerisms and conventions,” her works align with the modernist movement in literature and the secession in the visual arts. As a scholar writes, “without breaking new ground, she helped to bring a new range of expression into the traditional musical language.”

Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Piano Quintet in E Major, Op. 15

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957) was a true child prodigy. Some scholars even argue that he was the most remarkable prodigy in history “because of his extraordinary grasp of a language so complex at such a tender age.” His piano quintet in E Major, Op. 15, dates from 1921 and a period of distinct mastery. The listener is immediately immersed in a spatially expansive structure enriched by internal polyphonic nuances.

According to Habakuk Traber, “Korngold created his main themes via a vibrant surge of sound. A brief lyrical episode alleviates the tension, and a rhythmic motif represents a clear-cut, decisive burst of energy. As in the piano quintet, these surging openings are opposed by songful secondary ideas, whose main voice moves by steps, while the piano part breathes arpeggiated chords in the background. The entire work is informed by a thematic metamorphosis, including the variation movement. The finale leads back into the theme that had begun the entire work adhering to cyclical unity of form.

I trust you have enjoyed this additional excursion into the world of the piano quintet.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter