Bach

Throughout his extended Leipzig career, J. S. Bach had a rather uneasy relationship with civic and church authorities. At his election as Cantor of St. Thomas Church in 1723, Bach was cautioned to make compositions that were not theatrical. “In order to preserve the good order in the Churches,” Counsel Dr. Steger wrote, “so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such a nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion.” On 13 May 1723, Solomon Deyling — the superintendent minister in Leipzig — reported “Bach’s theological views had been examined and that he was theologically fit to assume the post.” From a theological standpoint, Bach’s collaboration on chapters 26 and 27 of the Gospel of Matthew with the poet Christian Friedrich Henrici — who wrote under the penname Picander — was squarely positioned in the mainstream of Lutheran orthodoxy.

J.S. Bach: St. Matthew Passion, BWV 244 (Georg Poplutz, tenor; Matthias Winckhler, bass; Julia Kleiter, soprano; Jasmin Maria Hörner, soprano; Gerhild Romberger, alto; Nohad Becker, alto; Daniel Sans, tenor; Christian Rathgeber, tenor; Christian Wagner, bass; Daniel Ochoa, bass; Johannes Hill, bass; Florian Küppers, bass; Mainz Bach Choir; Mainz Bach Orchestra; Hille Perl, viola da gamba; Jan Čižmář, lute; Sabine Bauer, harpsichord; Petra Morath-Pusinelli, organ; Ralf Otto, cond.)

From a musical perspective, however, the St. Matthew Passion was the longest and most elaborate work that Bach had ever composed. Three years after its initial performance on Good Friday afternoon, 11 April 1727, the church historian Christian Gerber writes, “If indeed it is true that there remains a place for moderate music in the church, especially as it is regarded as an ornament to the divine service, it is a well-known fact that very often the performances are excessive. This music often sounds so very worldly and jolly that it is more befitting a dance floor or an opera than a divine service. When this Passion music was performed for the first time in a distinguished city, by violins, numerous oboes, bassoons, and other instruments, many were amazed and did not know what to make of it. When the theatrical music struck up, all these persons were greatly astonished, looked at each other and said, “What shall become of this?” An elderly dowager warned, “Take heed, my children! It is like being at a comic opera.” All were most heartily displeased and raised just complaint.”

From a musical perspective, however, the St. Matthew Passion was the longest and most elaborate work that Bach had ever composed. Three years after its initial performance on Good Friday afternoon, 11 April 1727, the church historian Christian Gerber writes, “If indeed it is true that there remains a place for moderate music in the church, especially as it is regarded as an ornament to the divine service, it is a well-known fact that very often the performances are excessive. This music often sounds so very worldly and jolly that it is more befitting a dance floor or an opera than a divine service. When this Passion music was performed for the first time in a distinguished city, by violins, numerous oboes, bassoons, and other instruments, many were amazed and did not know what to make of it. When the theatrical music struck up, all these persons were greatly astonished, looked at each other and said, “What shall become of this?” An elderly dowager warned, “Take heed, my children! It is like being at a comic opera.” All were most heartily displeased and raised just complaint.”

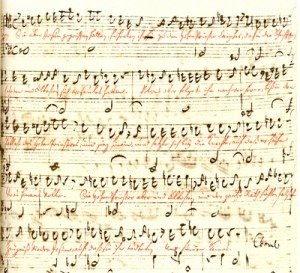

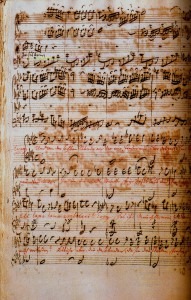

To be fair, Bach had already received similar complaints about his St. John Passion, conceived in Weimar but first performed in the Leipzig Nikolaikirche on 7 April 1724. Bach was severely reprimanded by his superiors with the immediate result that his compositional output declined rapidly. For Good Friday services in 1725 he relied on the music of his cousin Johann Ludwig Bach, and for 1726 he revived the St. Mark Passion by the Hamburg composer Reinhard Keiser. When Bach embarked on the composition of the Matthew Passion in 1727, he was keenly aware that a significant phase of his life was drawing to a close, and he celebrated this insight with a work that synthesized and surpassed all that he had previously composed in liturgical music. Although Bach would subsequently write several large-scale sacred compositions — the B-minor Mass, the Christmas Oratorio and the lost St. Mark Passion of 1731 — the St. Matthew Passion “was his last major composition for the Leipzig congregation.” Bach revived the St. Matthew Passion in 1736 with the principle aim to collect, organize and revise his own music. He made substantial revision and copied out an entire new score. This score, as has repeatedly been pointed out, is “one of the most beautiful manuscripts left by any composer,” as the most appropriate graphic presentation of the music led him to write the manuscript in two different colors of ink; the customary blackish brown for most of the work, and taking an obvious swipe at his superiors, a striking deep red ink for the chorale melody in the opening movement and all the words directly taken from the Gospel. I wonder if this gesture was at last properly understood?

To be fair, Bach had already received similar complaints about his St. John Passion, conceived in Weimar but first performed in the Leipzig Nikolaikirche on 7 April 1724. Bach was severely reprimanded by his superiors with the immediate result that his compositional output declined rapidly. For Good Friday services in 1725 he relied on the music of his cousin Johann Ludwig Bach, and for 1726 he revived the St. Mark Passion by the Hamburg composer Reinhard Keiser. When Bach embarked on the composition of the Matthew Passion in 1727, he was keenly aware that a significant phase of his life was drawing to a close, and he celebrated this insight with a work that synthesized and surpassed all that he had previously composed in liturgical music. Although Bach would subsequently write several large-scale sacred compositions — the B-minor Mass, the Christmas Oratorio and the lost St. Mark Passion of 1731 — the St. Matthew Passion “was his last major composition for the Leipzig congregation.” Bach revived the St. Matthew Passion in 1736 with the principle aim to collect, organize and revise his own music. He made substantial revision and copied out an entire new score. This score, as has repeatedly been pointed out, is “one of the most beautiful manuscripts left by any composer,” as the most appropriate graphic presentation of the music led him to write the manuscript in two different colors of ink; the customary blackish brown for most of the work, and taking an obvious swipe at his superiors, a striking deep red ink for the chorale melody in the opening movement and all the words directly taken from the Gospel. I wonder if this gesture was at last properly understood?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter