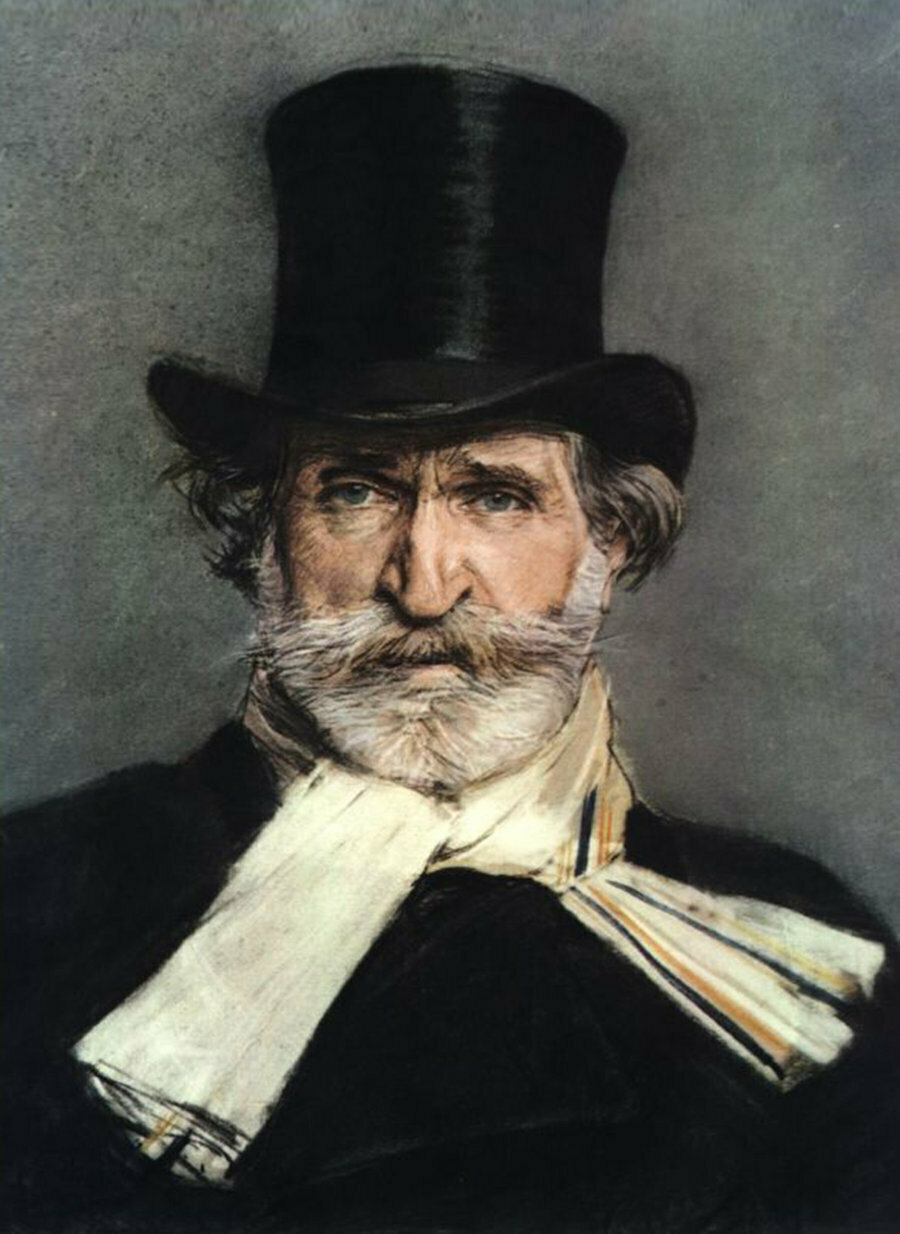

In 2024, we commemorate the 50th anniversary of the death of Frank Martin (1890-1974). One of the foremost Swiss composers of the 20th century, Martin was a highly versatile and eclectic composer who spoke with an authentic personal voice that crossed the divide between conservative and avant-garde trends while subsuming French and German cultural traditions.

Frank Martin

Fifty years after his death, what remains of Frank Martin? If we were to look only at the number of public performances of his works, we might be tempted to worry. But that would be to forget that today a musician’s popularity or standing can no longer be measured by concerts alone. The circulation of recordings, including those no longer available commercially, defies any attempt at tracing them, and the fervour we devote to a creator is in any case not a purely quantitative thing. In the specific case of Frank Martin, the recent release of a number of new disc interpretations of his works, which have also been very well received by the critics, clearly shows the persistence of ardour among both musicians and music lovers. This is a particularly pleasing sign, coming as it does from a country not renowned for giving Martin’s music wide coverage: the French magazine Diapason, whose authority and influence in the field of classical music is undeniable, has zealously and enthusiastically relayed most of Martin’s major discographic releases in recent years: ‘Diapasons d’or’ for the first complete recording of La Tempête (2011) and for the complete works for flute by Emmanuel Pahud (2012), five diapasons (the highest mark after the diapason d’or) for Le Conte de Cendrillon (2012), the Cello Concerto performed by Estelle Revaz (2021), the Violin Concerto by Svatlin Roussev (2021) and for the release of the old recording (1979) of the Requiem by Leif Segerstam (2022). The latter recording in particular proved important for at least three reasons: it was by a conductor with a well-established international reputation, it was coupled with Janacek’s Otcenás cantata, thus putting Frank Martin on the same footing as the great Moravian composer, and above all it rehabilitated a work which, even among our musician’s diehard fans, has rarely been considered one of his greatest achievements. In fact, without wishing to criticise the historic performance of the Requiem conducted by the composer himself a year before his death, it has to be said that Segerstam’s version surpasses it and gives this somewhat unloved work a breath of fresh air that compels us to reconsider its value: the Martin who expresses himself here truly appears to be in search of an ultimate style, more hieratic if not more symbolic, and with a particularly visionary tone.

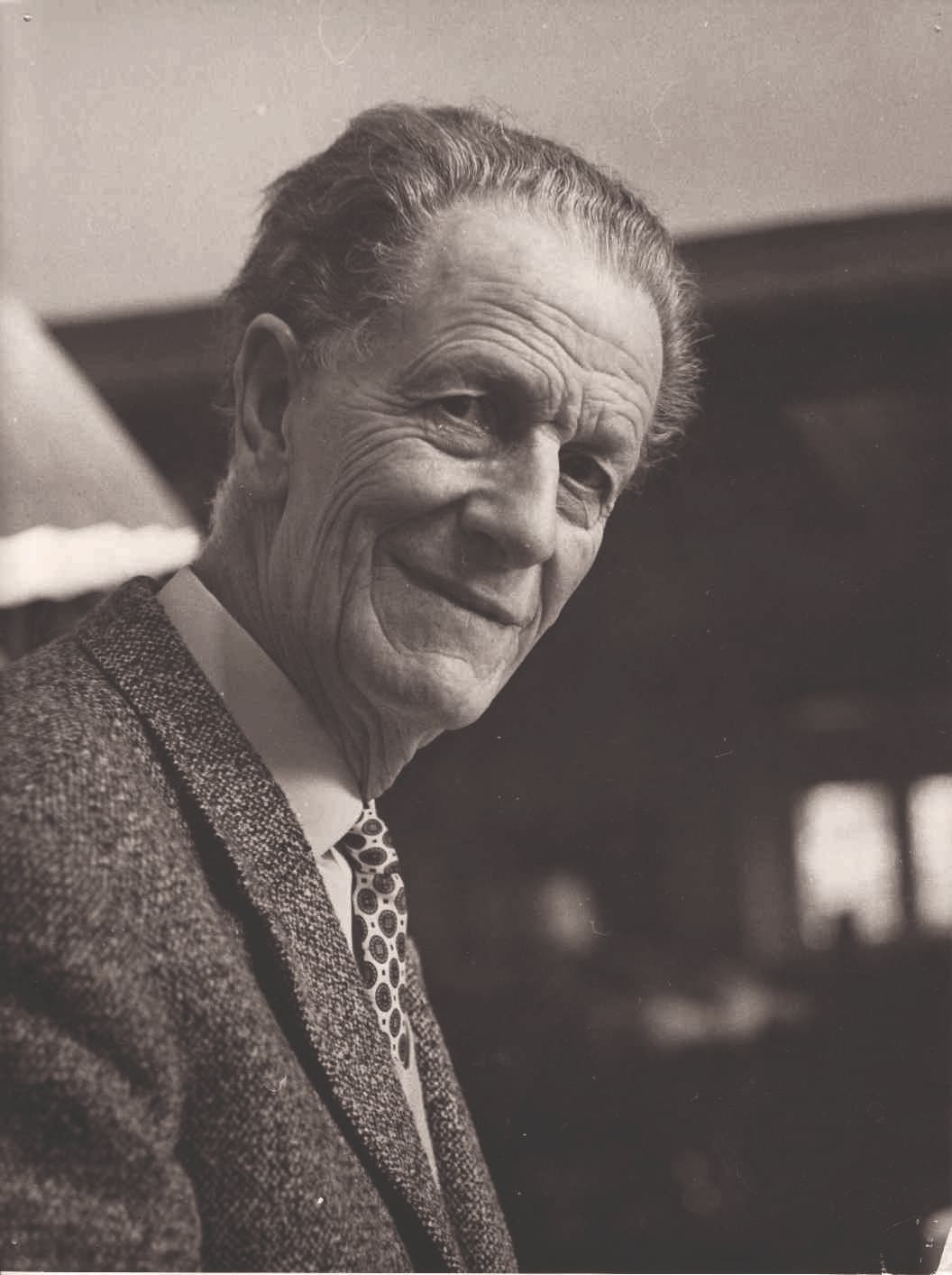

Frank Martin at 20 years old

If one wonders which are the favourites of Martin’s discography, it is probably the Messe à double chœur (Mass for Double Choir) that should be singled out: not only are its recordings numerous, but their quality is often first-rate; sung by some of the best chamber choirs in the world (English as well as Dutch and Swedish. It is undoubtedly one of the most popular works of religious music of the twentieth century. It is certainly regrettable that this early work (1926) tends to overshadow the spiritual masterpieces of maturity such as In Terra Pax (1945) and Golgotha (1948), but this does not mean that these latter works are impossible to find, and we have just heard of the Requiem‘s recent and unexpected revival. Moreover, the fact that the Frank Martin of the 1920s is less ‘personal’ than that of the 1940s is both obvious and somewhat misleading, since the diatonic purity of many of the ‘early Martin’ works gives his output from that period a particularly endearing timelessness. Classical rather than ‘neo-classical’, the style of the Martin of the 1920s can be found in his mature works whenever the need for simplicity was felt, in contrast to his writing which had become more chromatic and tense: thus Le Mystère de la Nativité, the Cello Concerto or the Polyptych (and even Golgotha) contain these protected oases, reconnecting us with a ‘young Martin’ who never completely disappeared.

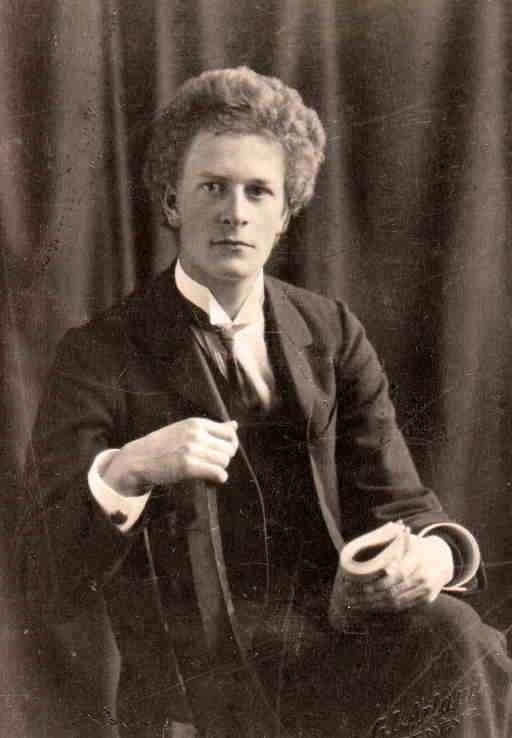

Frank Martin during rehearsal of Der Sturm 1956 © Gretl Geiger

Among the other pieces most often recorded is another from the first period: the Trio on Irish folk melodies (1925), whose variety of interpretations is highly significant; there is even a version interspersed with ‘stolen’ jazz effects by Jérôme Berney’s ensemble (2010), which underlines its rhythmic genius and highlights particularly well the originality of this piece, even unique in Martin’s output. The technical perfection of the performance by the Zurich chamber musicians on a Jecklin disc (1990), which also offered magnificent interpretations of the 1919 Piano Quintet, the ever-popular 1920 Pavane couleur du temps and the harsh 1936 String Trio (the only recording ever), is certainly to be preferred for this work, but that disc has unfortunately long been out of print, which is a great pity, because Martin’s chamber music has never before shone so brightly.

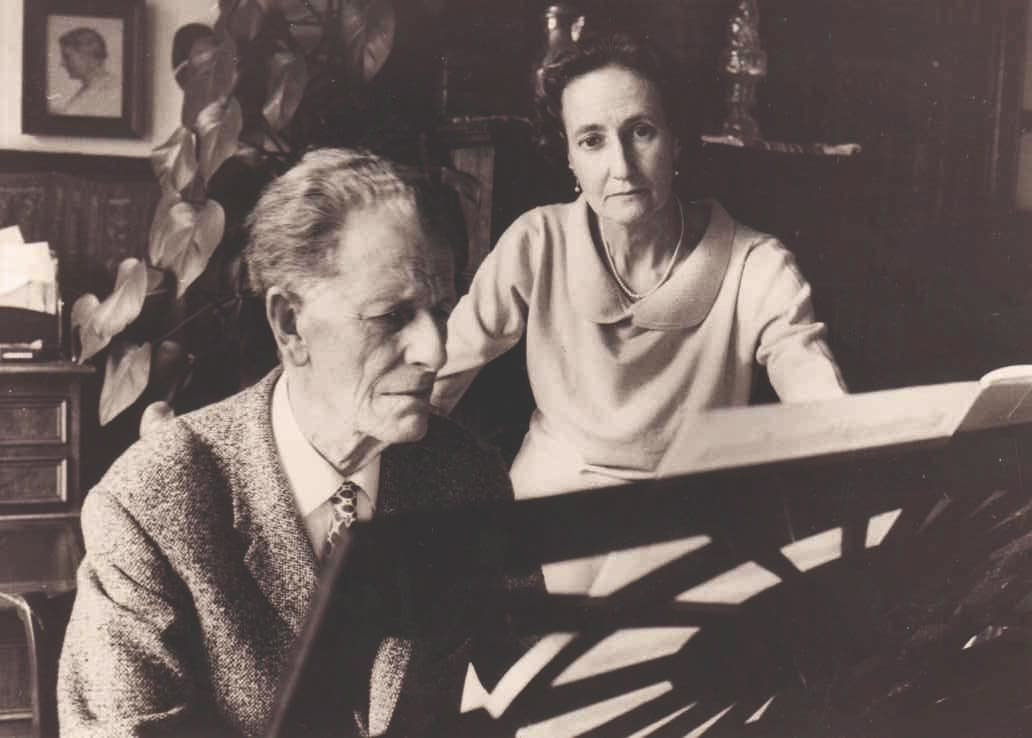

Frank and Maria Martin at the piano

Fortunately, if some works are in decline, others reappear almost miraculously. In fact, despite the quality of Svetlin Roussev’s interpretation of the Violin Concerto, what might well give his disc its greatest value is the truly unknown 1920 Sketch for Orchestra that completes the programme. Here we are faced with a Frank Martin barely thirty years old who has just broken with the post-romanticism of his early works and gives us, with incredible freshness and verve, a piece that its modest title of Esquisse designates as a kind of improvisation and which, while it is in the tradition of what might be called the ‘national school of French-speaking Switzerland’ (there are allusions to Jaques-Dalcroze), it is already very characteristic of Frank Martin, with the lively nervousness, the abrupt rhythm and the poignant nostalgia that will remain his trademarks.

The resurrection of this Esquisse also reopens the debate on Martin’s orchestral works, most of which remain in the shadow of his concertante music. This is perhaps not entirely untrue, since the form of soloists and orchestra has proved to be Martin’s preferred mode of instrumental expression. The rich discography of most of the Ballades shows, moreover, that this is also the opinion of their performers. It should also be remembered that the only recordings made of the two most ambitious orchestral works of Martin’s maturity, the 1937 Symphony and the 1969 Erasmi Monumentum by Mathias Bamert on Chandos (1994), have not proved very convincing. The fact is that pieces as modest as the Overture in Homage to Mozart (1956), the Rondeau Overture (1958) and Inter arma caritas, composed for the Centenary of the Red Cross (1963), are still waiting to be recorded. Not to mention Rythmes (1926), a fundamental triptych in Martin’s development, which has never been commercially recorded. The same fate befell the Dithyrambes of 1918, an oratorio that is admittedly still fairly post-romantic, but whose vast dimensions (a good hour of music) should bring it to the attention of all lovers of Frank Martin’s music: here we hear passages that astonishingly foreshadow his late chromatic style.

La Nique à Satan premiere, 25-02-1933, with Pauline Martin as La Bergougne surrounded by devils

Another work that urgently needs to be brought out of the boxes of private recordings is La Nique à Satan. Radio Suisse Romande released a version of this work, but it was so rarely broadcast that it soon became impossible to find. Bringing this work back to light would prove to all those who find Martin ‘too Protestant’ that our composer also knows how to be ironic and caustic, even anti-establishment (a former teacher of the author of these lines read in La Nique à Satan a political psychodrama particularly well suited to the fate of the town in the Neuchâtel Jura where he taught…). It is true, to stay in the realm of amusing music, that the recording of Monsieur de Pourceaugnac has passed a little less unnoticed, and that a recent issue of Diapason (February 2022) cited it, in a dossier on Molière, as one of the ten most important musical works inspired by the great French comic author. Even so, much remains to be done to revitalise the comic aspects of Martin’s work. In this respect, the 1915 Symphonie pour orchestre burlesque, which the composer revised at the end of his life for a private performance, undoubtedly deserves to be unearthed: it would undoubtedly offer a welcome alternative to Leopold Mozart’s eternal Symphonie des jouets, which lovers of farcical music crave to no end.

Frank Martin: Ballade for Flute and Piano (Emmanuel Pahud, flute; Francesco Piemontesi, piano)

Frank Martin & Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Berlin 1963

One of the positive aspects of Frank Martin’s reception is that, as typically Genevan as he may sometimes seem, he is still performed just as much in German-speaking Switzerland as in French-speaking Switzerland. It is true that his predilection for setting German texts to music (Le Cornet, the Jedermann Monologues and even Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which he preferred to set to music in Schlegel’s translation rather than in its original version – with the exception of Ariel’s Songs for which he adapted a version in Shakespeare’s language) has brought him much closer to German culture (or Swiss German, as in his 1943 Basel Danse des morts). In return, dare we say it, works in French have not been shunned by German performers either, as testified by the relatively recent superb versions of Le Mystère de la Nativité by Aloïs Koch (2001) and Le Vin herbé by Daniel Reuss (2007); and we must salute the efforts of the three Swiss-German singers who recorded the Trois poèmes de la Mort in 2009 (on a disc of Martin’s complete guitar works), even if their French pronunciation is not perfect and the electric guitars lack a little bite…

Concerning the combination of stage and orchestra, a final remark should be made about the most neglected part of Martin’s work: his incidental music, of which no recordings exist, not even a partial one. Admittedly, most of these works were written in his youth and for particular occasions, but it would still be astonishing if his music for Œdipe-Roi (1923), Œdipe à Colone (1924), Roméo et Juliette (1929) and La Voix des siècles (1942) did not contain a single page worthy of survival.

Alain Corbellari

In conclusion, in addition to Martin’s prize works (Vin herbé, Cornet, Petite symphonie concertante, Monologues de Jedermann, Golgotha, Préludes), many of his concertante pieces and a small selection of works from the first period remain easily accessible to music lovers. But the renewal of interpretations could be more sustained, and work on the side-lines of his output remains necessary. We can wager that Frank Martin and his musicians have not said their last word.

Alain Corbellari is Professor of Medieval French Literature at the Universities of Lausanne and Neuchâtel. A specialist in the history of medieval studies (and in particular the figure of Joseph Bédier) and the reception of the Middle Ages in Modernity, he has also worked on the relationship between literature and music, particularly in the works of Romain Rolland and Charles-Albert Cingria. He is the author of the most recent biography of Frank Martin, Frank Martin, un lyrisme intranquille, Lausanne: Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, “Le Savoir suisse”, 2021.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter