© medium.com

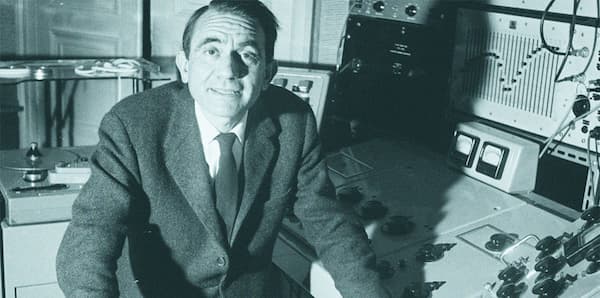

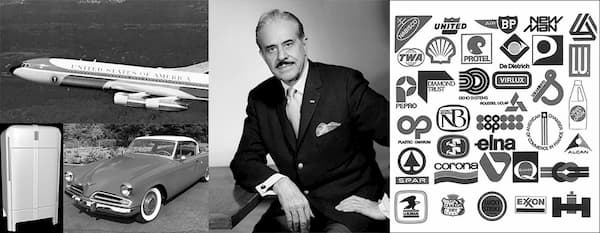

Raymond Loewy is a famous industrial designer, responsible for some of the most famous designs of the 21st century; the Coca-Cola bottle, the Shell Oil logo, the US Postal Service logo etc. His approach to design is well-known under the acronym MAYA, or Most Advanced Yet Acceptable. It is the idea of creating a product that innovates yet remains acceptable and understandable to users. It is a balance between the present and the future.

Raymond Loewy and his famous designs © Archbridge Institute

MAYA can of course be applied to music. Indeed, composers spend most of their time finding balance in their works; whether it is through following historical theoretical and structural rules, emotional impulses, research for musical innovation and pleasing the ear of the listener. Most composers who follow such rules are rarely thought of real innovators — which brings the whole Second School of Vienna out of the discussion.

Schubert, Chopin or Liszt for instance, can all be included in the followers of some sort of MAYA musical principle: harmonic or technical innovation in disguise. Debussy, Ravel and Satie as well. Glass is also a very successful MAYA innovator — having merged the East and the West seamlessly — as opposed to Reich, who leaned towards musical progress rather than popular success. Today a great applicant of the MAYA principle is Einaudi, who plays pleasant innovative music in disguise — let’s not forget that he was once a student of Berio.

© Echo magazine

What is not MAYA then is much of what some might consider as avant-garde music or simply experimental: from Bartók, Stravinksy, Schoenberg, Berg to Cage, Xenakis, Berio, Messiaen and much of contemporary music. It is music that defies norms and traditions, it is progressive and somehow aggressive in its approach.

Music that is not MAYA is hugely important, as it allows great leaps towards progress, and influences composers that are less adventurous. I often think of Beethoven — who we would probably associate with MAYA for most of his career— and his Grosse Fugue. Hugely criticised during its release — it was meant to be the finale of his Quartet No. 13 in B-Flat Major — the composer was forced to write an alternative movement in order to be accepted by the audience of the time. The fugue that was once too progressive is today regarded as one of his most successful pieces.

There is a great example in jazz, and particularly in the difference between the approach of Miles Davis and John Coltrane. The impact that both had on music, and particularly jazz, is indisputable. However, the two musicians took a very different approach to progress. While Davis seemed to integrate innovations seamlessly — through MAYA —, Coltrane seemed a lot more direct and brutal in his approach. To understand the difference between both, one only needs to listen to the trumpet — Davis — and the saxophone — Coltrane — solos in “So What”. The chord progression — itself innovative in its use of both modal and quartal harmony — is used again by Coltrane in “Impressions”, to a completely different result. It is no surprise that King of Blue has often been regarded as one of the greatest jazz records ever.

Snarky Puppy © images.squarespace-cdn.com

A few ways composers can include MAYA in their own works include advancing the musical innovations gradually over time, including familiar melodic and rhythmical ideas alongside more daring ones, draw on what is currently deemed acceptable and use it as a basis for more advanced work, and listening back to other works in order to understand what has been accepted and can now be considered bearable.

In a masterclass, the modern jazz ensemble Snarky Puppy once said: if you want to have fun with rhythm, be simple with melody and harmony — and vice-versa —, and this draws directly on the MAYA principle. This principle can be understood as finding some sort of balance: between consonance and dissonance, ease and difficulty, intellect and heart, pleasing and daring, familiar and strange, tradition and innovation.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter