In my last article I discussed Čiurlionis’ genius, single-handedly introducing Symbolism to his native Lithuania. Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) in contrast, lived and worked within well-established artistic traditions in Russia, in which the various avant-garde movements in music and art from Western Europe had flourished. By 1893, the works of Verlaine, Mallarmé, Maeterlinck, Poe, Ibsen, Strindberg had been translated into Russian as had Schopenhauer’s work ‘Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung’ (The World as Will and Presentation). Kant and Nietzsche were also widely read in Russia at that time.

Alexander Scriabin

Initially a literary-philosophical movement, Russian Symbolism grew from these western European roots, and took different forms in the musical circles of St. Petersburg and Moscow. St. Petersburg, always more directed to and open towards the west — Czar Peter the Great had founded the city as a ‘Window to the West’ — produced many great operatic composers, such as Glinka, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, whose opera ‘The Golden Cockerel’ can be considered to follow the Symbolist tradition. The Moscow School, more oriented towards ‘Old Russia’ and its mystical past, primarily focused on instrumental music with composers such as Scriabin, Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff. Scriabin wrote mainly for the piano, with — among his oeuvre — ten sonatas, 83 preludes, 101 piano pieces; five symphonies, one piano concerto. He frequented the Symbolist literary circle in Moscow, whose greatest theoretician was Andrej Belyi.

Alexander Scriabin: Piano Sonata No. 3 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 23 (Glenn Gould, piano)

Title Page For Scriabin’s – Symphonie Prométhée

In 1904 Scriabin participated in the Fourth Philosophical Congress in Geneva, whose main topics were the works of Fichte and Bergson. In his annotated notes of the various lectures, Scriabin focused on the ideas of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, in particular on Nietzsche’s ‘Zarathustra’ and the concept of the ‘Űbermensch’ – Nietzsche’s ‘Superman’. In his later years, he would see himself as a ‘Superman’, who would lead like a prophet, evoking Baudelaire’s concept of the role of the poet, and would liberate humanity through the ‘mystery of music, color, dance, and scents’ – through the experience of true ‘synesthesia’. Artistic creation for him became a state of ‘mystical ecstasy’ similar to a divine revelation. His symphonies from then on carry titles such as ‘poèmes/poems’ e.g. ‘Le divin poème/The divine poem’, Symphony No. 3; ‘Le poème de l’Extase/Poem of Ecstasy’ op. 54’, Symphony No.4, 1908; ‘Prométée/Prometheus’, ‘Le poème du feu/Poem of Fire’, Symphonie No. 5, 1911 for piano, choir and color piano.

Alexander Scriabin: Le poeme de l’extase (The Poem of Ecstasy), Op. 54, “Symphony No. 4” (Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Vladimir Ashkenazy, cond.)

With this Prometheus composition, Scriabin enters the realm of the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, the concept of the ‘total work of art’, where music, colors (the predominant force), word elements and philosophy all work together. The piano in ‘Prometheus’ embodies the Promethean spirit, which shows man defying the gods in bringing fire to the earth, for which Scriabin invented a new tonality, the so-called ‘Promethean or mystic chord’ – a six-note synthetic chord, outside of major and minor chords. Many of his subsequent works include the use of this chord, with derivations emerging from its transpositions.

Many composers of the 20th and 21st centuries also have used this chord in various ways, especially as the use of dissonant sonorities became more prevalent.

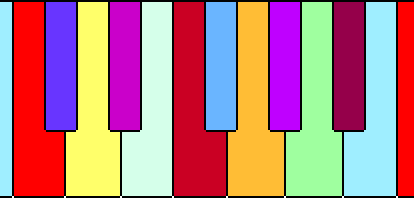

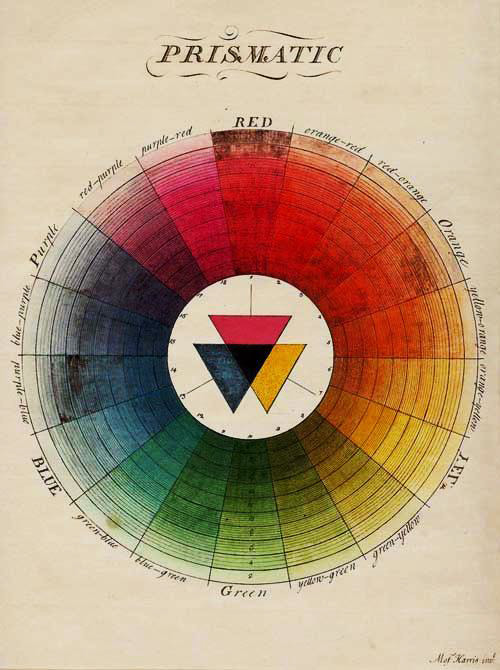

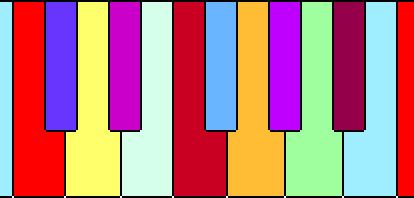

Colors then, in the Color Piano are assigned specific roles, i.e., as the tones change, the colors also change. For example: F# is not just a chord assigned the color ‘blue’, but at the same time a mood, voilé, mystérieux/veiled, mysterious; ‘yellow’ not only uses the chords of D, G#, C, F#, B, E, but conveys a happy mood, plus animé, joyeux/more lively, happy. ‘Red’, voluptueux presque avec douleur/voluptuous almost with distress, is the color of ecstasy. Scriabin’s choices of colors were not by happenstance, but followed the color-theory of Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), who had based his theories on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s ‘Farbenlehre/Color Theory’, published in 1810.

Alexander Scriabin: Prometheus, Op. 60, “The Poem of Fire” (Dmitri Alexeev, piano; Philadelphia Choral Arts Society; Philadelphia Orchestra; Riccardo Muti, cond.)

Scriabin’s Color Piano Keys

Inspired by his Prometheus, Scriabin continued to explore the ideas of a ‘mystery’, linking music, poetry, and dance, leading to the redemption of humanity through a symphony of sound, light, color, and scents which would envelop the listener and bring him to a state of ecstasy. For Scriabin, colors had become the means – color as sound-intoxication and color-intoxication as sound. In the final analysis, he did not become a painter-composer like Čiurlionis, Schoenberg, Satie or Hindemith, or a composer like Mussorgsky with his ‘Pictures at an Exhibition’ – but remained a philosopher-composer.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter