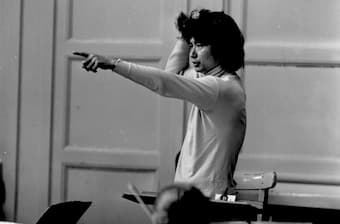

Seiji Ozawa, 1963

The iconic Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa is internationally known for his energetic conducting style and his advocacy of modern composers. He attributes his involved podium style to his first conducting teacher, Saito, and to the language barrier he feels he still faces. Audiences around the world have responded to his dance-like conducting, “and he is well respected by musicians for his skilled baton and rehearsal technique, his even temperament, and his detailed, intensive preparation.” Ozawa conducts the most difficult scores from memory, and he delights in large-scale words by Berlioz, Brahms, and Mahler. In addition, Ozawa has showcased nearly all of Schoenberg’s orchestral music, and a wide range of Stravinsky’s works. Critics suggest “that some of his best early recordings are of Lutosławski, Honegger and Messiaen’s Turangalîla. Strauss, Bartók, Debussy, Ravel, Messiaen and Takemitsu have all remained in his repertory, and he has given the premières of new works by Peter Maxwell Davies, Lukas Foss and many others.”

Seiji Ozawa Conducts Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra

Seiji Ozawa conducting

Seiji Ozawa is one of the most instantly recognizable figures on the podium, “and the first from Japan to achieve star status in the West.” In fact, Ozawa was born on 1 September 1935 in the Japanese-occupied city of Mukden, presently Shenyang, Liaoning, in the People’s Republic of China. The family moved to Beijing in 1936 and settled in a traditional courtyard home in the Chinese capital. When his mother passed away in 2002, she left instructions that her ashes should be interred in the courtyard garden. At that time, Ozawa accompanied his mother’s remains to his former neighborhood and said, “I miss my childhood home very much.” When his family returned to Japan in 1944, he started school as a quasi-foreigner. “I was half Chinese and half Japanese, my language.” However, Ozawa always considered himself Japanese, and he was able to achieve success without sacrificing his Japanese identity. “I am Oriental,” he explains, “and sometimes I say, why I become Western music musician? But I think that made my life much more interesting, much more exciting. But I had to pay a price.”

Seiji Ozawa Conducts Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4

Ozawa and Karajan

Ozawa began his piano studies with Noboru Toyomasu, “heavily studying the works of Johann Sebastian Bach.” Actually, young Seiji had two burning passions; one was to become a famous pianist and the other was playing rugby. As a serious piano student, “I hid that fact from my family as I knew that piano and rugby don’t work together well. It was very secret, but I was absolutely passionate about rugby. Not unexpectedly, he had a rugby accident and broke two fingers. “I was number 8 on the field,” he says referring to the position he played on the rugby team. “That position is very important in making decisions, so I think they attacked me on purpose.” As might well be imagined, the aftermath was rather unpleasant but his piano teacher suggested, “that Seiji should not give up music completely. There is a way to stay in music if you become an orchestra conductor.” Ozawa had never watched a conductor and had never been to an orchestra concert, but then he saw the conductor and pianist Leonid Kreutzer conduct Beethoven’s fifth piano concerto from the keyboard. “I thought that was amazing,” Ozawa says.

Toru Takemitsu: November Steps (Kinshi Tsuruta, biwa; Katsuya Yokoyama, shakuhachi; Saito Kinen Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Hideo Saito

After his mother had been told of his new ambition, “she remembered that a distant relative was a conducting teacher. So she wrote a letter of introduction for her son to Hideo Saito, who happened to be one of the leading music pedagogues in Japan, and who was to become Ozawa’s main mentor and influence for the rest of his life.” Hideo Saito was an outstanding cellist, composer, and pedagogue. He devised a unique collection of terms for talking about conducting, and assembled a set of exercises designed to facilitate the practice of a variety of gestures.

Ozawa and Saito

“While he pays attention to time, space, direction, size, and expectations, he often explores the ways and changes in velocity that can be employed to elicit desired sounds from players and singers.” Saito taught Ozawa to conduct with technical brilliance and without repertory specialty. 10 years after breaking his fingers Ozawa won first prize at the International Competition of Orchestra Conductors in Besançon, France, and in 1960 he won the Koussevitzky Prize for outstanding student conductor, Tanglewood’s highest honor. The rest, as they say, is history, as Ozawa would go on to rule the Boston Symphony Orchestra for a record 29 years.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Seiji Ozawa Conducts Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps

One of my idols. Wow

So very interesting, I taught piano for 45 years, so music is planted deep in my soul!