Reconciling Worlds

Described as ‘one of the most exciting young pianists of our time’ (Arts Desk), pianist-composer George Fu is based in London but splits his time between Europe and the US, where he has performed at venues including the Southbank Centre, Kings Place, Kennedy Center, Konzerthaus Berlin, and Tanglewood.

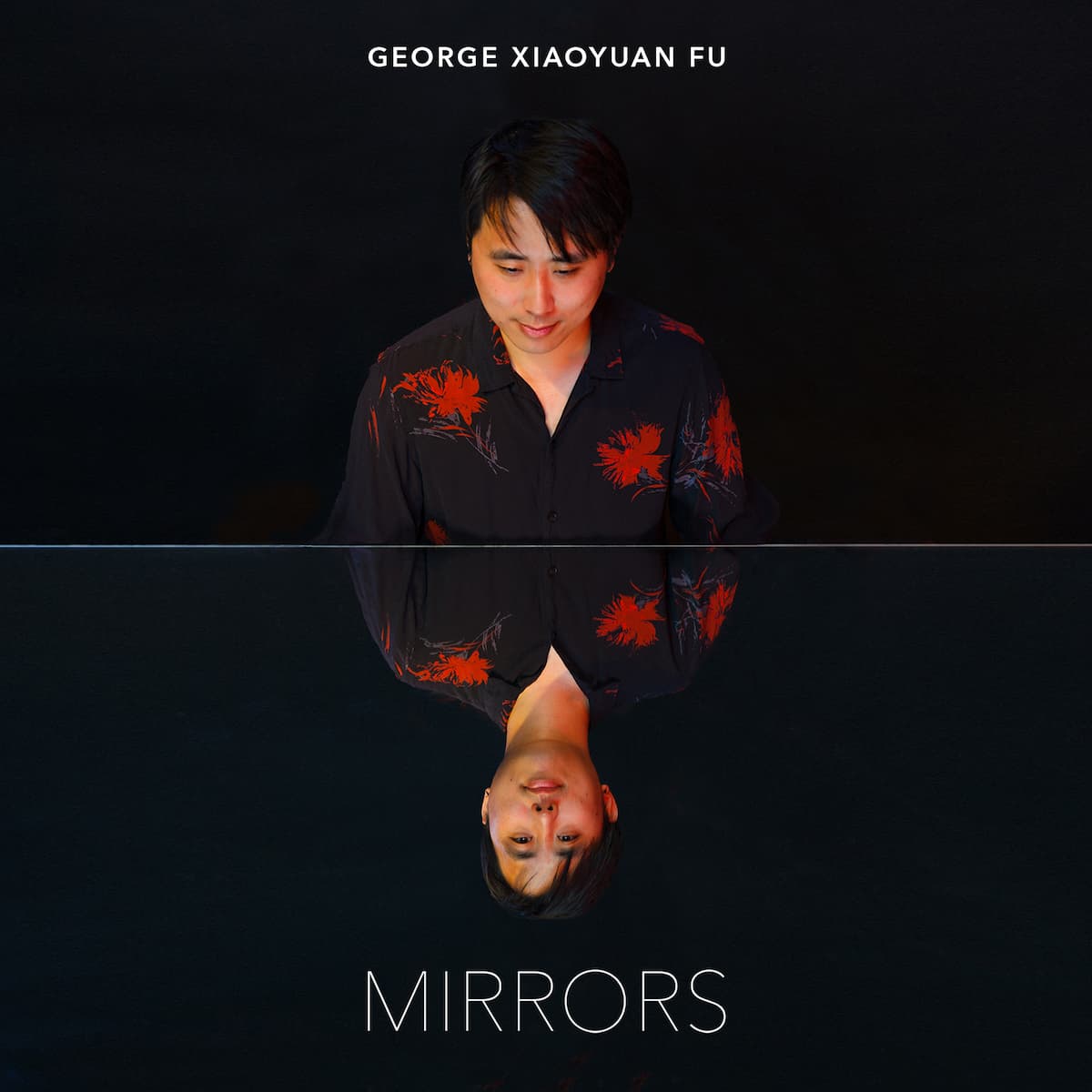

Renowned for his interpretations of modern music, his debut album Mirrors, which features Ravel’s piece of the same name (Miroirs) as a springboard for an eclectic exploration of contemporary piano repertoire, received high praise from both Gramophone and BBC Music magazines.

I talked to George at his home in London about the process of recording, and how the past informs the choices we make as musicians today.

George Xiaoyuan FU — passacaglia on a theme by radiohead

How did you start learning the piano?

I was five when I started. I remember there’s a story of me, at three or four years old, stealing an electric piano from a yard sale – which my parents obviously paid for afterwards! I was playing by ear at the time, I just sort of started.

I knew I was good at it, but I didn’t know what a career looked like. My father really only started going to concerts after I started studying the piano, and then he ended up being a classical music fan. He went to lots of concerts, and he really got into it through me, and my mom too. It just really goes to show how important exposure is.

I think in the States a lot of literacy towards classical music is low, outside of some cultural centres. A lot of work has to be done to even just get people to know what is out there. My family fell under that umbrella, I think. If you know, you’re in, and if you don’t know you’re out, and I’m really resistant to that because if that was the case for me I never would’ve started doing this, this never would’ve been my life.

George Fu © Benjamin Ealovega

How does your composing work relate to your performing?

I have written since I was a child, but the problem is […] my repertoire is very large. And when you have a large repertoire you know what’s really good, and so therefore when you start writing, it’s very hard to turn that voice off in your head.

I am not actually that interested in writing for anybody other than myself. And I think it used to really bother me and it used to prevent me from even writing because I thought: ‘Well, I guess I’m not a composer.’

But actually, I am a composer – I’m a pianist-composer. The bulk of my work is in interpreting, and I really love interpreting, but occasionally I do enjoy writing original music. It helps me also to understand interpretation more, and interpreting also feeds back into composing.

I’m trying to do a project on Chinese folk songs, where I transcribe them for violin and piano. That’s very personal to me, and […] to just be in that space where no one’s done what I’ve written before, to find that space and also just make it for yourself, that’s taken me quite a long time to do.

© Raphael Neal

The concept of your album Mirrors is so strong. How did it feel to record?

It was really refreshing to go in there with an idea and really have a chance to get exactly what you want, because in a live circumstance, it’s so mercurial, so much is left up to chance. Of course, there’s that in the studio, but you get to have the luxury of really pushing it in the direction you would want.

How do you balance the need for spontaneity versus security in the recording process?

Someone very wise told me that if you’re going to record something and have it be an album, it has to somehow represent something that they might hear you play in a concert. I never would want to do a representation that is not something that you might hear in a live circumstance, so it has to resemble something spontaneous.

That’s something very difficult to remember, but in a recording studio, if you don’t do that then what’s the point of even recording it, in my opinion.

© fanjulandward.com

How do you reconcile that with today’s obsession with recording things that sound ‘perfect’?

When you hear recordings made by Ricardo Viñes – he was the guy who premiered so much stuff by Ravel and Debussy and Albeniz, all of those composers working in France at the time – a lot of the stuff he’s doing is really wild.

He was working with these composers, and the composers had a lot of control over what they wanted to hear, and yet the interpretative liberties he’s taking is something that to many people would be very unacceptable now.

So there’s the digital element of the recording and then there’s the actual interpretative trend nowadays, which is much more diligent, much more fastidious, I think. Given that that’s the style that people are interpreting [in] these days, it’s really up to us to decide whether that’s an impediment or something that gives more colour.

I’m a pianist in this day and age, I’m influenced by many different things, and I don’t want to be too self-conscious about that, actually. I think in some ways I know that I’m pretty fastidious about how things are, but I think of that as a virtue. One of the things in our modern society is that you’ve got to have the thing that you do, and believe in it totally, and completely accept when somebody comes from the other angle entirely.

It also depends on the repertoire. I think there are some pieces for which, if I’m sitting at the back of the hall and I can transcribe what’s on the score from your performance then that is a great performance. And there’s other repertoire where that would just absolutely give the worst, most boring, prosaic thing ever. Like Schumann, for example. He’s somebody for whom if I can tell exactly how he’s written it I don’t think that’s a particularly good performance. I think his music is much more representative, rather than literal.

Debussy: Étude No. 6 “pour les huit doigts”

Which angle are you coming from in Mirrors?

In my own musical education, I’ve had two huge interpretative influences. One of them was discovering really old recordings, particularly of Alfred Cortot, Benno Moiseiwitsch, and Ignaz Friedman, usually playing Chopin, which is funny because I don’t really play much Chopin, but their relationship with the score is very honest and loose.

And then the other side of it was when I spent some time studying with Pierre-Laurent Aimard. For about two years we had a few classes together, and that also really focused on how I saw the relationship to the score. He has such command in his fingers but also his ears are open in such an interesting way, and when I get to play I almost feel like I’m reconciling those worlds.

In the end, we all want something to sound very spontaneous, but they are such different approaches, and yet both of them are so true to what you see in the music, and so that’s kind of where I feel like I’m living, right now.

If you ask me in another few years maybe that would be different. If I do record Beethoven sometime, which I might, I will have in my mind recordings of Wilhem Kempff, Artur Schnabel, Alfred Brendel, Paul Lewis, Mitsuko Uchida… and you then say, ‘Well that exists and that’s pretty damn good, but this is what I believe.’ You have to have that conviction, to say ‘That’s good, but mine is good too,’ and we’re all, in the end, I think, going for the same thing.

And it’s actually pretty beautiful. I think that’s what gives what we do that longevity.

George’s album Mirrors is out now.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Rachmaninoff/J. S. Bach – Gavotte from Partita no. 3 (George Xiaoyuan Fu, piano)