The music of Johann Sebastian Bach has long served as a wellspring of inspiration for composers across centuries. From the Classical era to the Romantic period and beyond, Bach’s music has been adapted for new instruments, ensembles, and audiences.

Johann Sebastian Bach

Even today, we are surrounded by popular arrangements of Bach’s music every day in the context of jazz, rock, pop, and film scores. While often creative, they cater to broad audiences and reflect contemporary trends rather than a deep engagement with Bach’s original intent.

In this tribute to Bach’s birthday on 21 March 1685, I am less interested in commercial appeal but will focus on the intellectual and artistic dialogue between Bach’s legacy and composers like Mozart, Beethoven, Raff, Elgar, Respighi, Mahler, and Schoenberg.

Arrangements of Bach’s music often disclose pedagogical or interpretive intent. In addition, we also find attempts to preserve Bach’s legacy and reveal evolving tastes and technical possibilities that merge Bach’s music with later stylistic innovations. In this blog, I am particularly interested, with one exception, in the transfer of Bach’s keyboard music into different performance mediums by legacy composers.

Mozart/Bach

Mozart/Bach: Preludes and Fugues, K. 404a

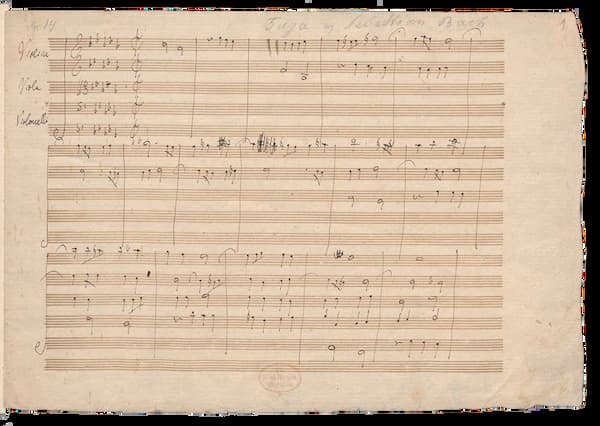

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart engaged with Bach’s music late in his career, as he encountered Bach’s music through the Viennese circle of Baron Gottfried van Swieten in the early 1780s. During Sunday gatherings at van Swieten’s home, Mozart participated in performances of Bach’s music. Some sources suggest that Mozart initially arranged selected preludes and fugues from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier for string trio, and that he later expanded some of these pieces for string quartet.

Mozart was apparently rather enthusiastic and wrote to his sister in April 1782. “I go every Sunday at twelve o’clock to the Baron van Swieten, where nothing is played but Handel and Bach. I am collecting their fugues now.” The purpose of Mozart’s arrangements was likely for private performances at van Swieten, serving as both a study exercise and a means to share Bach’s music with his peers.

Mozart/Bach: Preludes and Fugues, K. 404a

Mozart’s arrangements are relatively faithful to Bach’s originals, focusing on clarity of voices rather than Romantic-era embellishment. He avoided extensive ornamentation and did not alter the harmonic structure, but instead preserved the intellectual rigor of Bach’s counterpoint. As a performer, Mozart adapted the fugues to suit the idiomatic capabilities of strings, occasionally adjusting ranges or dynamics to enhance playability and expression in a chamber setting.

While modest in scope, the Mozart arrangements are significant as he begins to incorporate counterpoint and fugues into his own composition. After all, the Jupiter Symphony, the Adagio and Fugue in C minor and the Requiem are the immediate outcome of his engagement with Bach. The Mozart arrangements reflect his deep respect for Bach’s craft and his own evolution as a composer, blending Baroque complexity with classical elegance.

Beethoven/Bach

Beethoven/Bach: WTC 1, Fugue in B-flat minor, BWV 867 (Sofia Kim, violin; Susie Kroh, violin; Seido Karasaki, viola; Hrafnhildur Marta Guðmundsdóttir, cello; Lawrence DiBello, cello)

Beethoven’s engagement with Bach was primarily didactic. He studied Bach’s music, adapted it, and it greatly influenced his own compositions. At the age of 11 or 12, Beethoven first encountered the WTC through his Bonn teacher Christian Gottlob Neefe. No surviving manuscript explicitly shows Beethoven transcribing Bach from that time, but he seems to have adapted the music for his own practice.

We know from Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny, that he revered Bach fugues and used them as teaching tools. These adaptations were not grand orchestral re-imaginings but practical reworkings. As Beethoven writes, “Bach’s music represents a pure stream of musical thought… worthy of deep study.”

Beethoven/Bach: String Quintet

Beethoven had written a number of two-voice counterpoint exercises during his time in Bonn, but once he made his way to Vienna, his interest in Bach ignited. An arrangement for string quintet of the Fugue No. 24 from the WTC I, catalogues as Hess 38, dates between 1801 and 1802. This effort reveals a composer who grappled with Bach’s genius not to reframe it for others, but to forge his own path.

This Beethoven/Bach arrangement is a deeply personal dialogue rather than a public reinterpretation. From this introspective approach, Beethoven absorbed and refracted Bach’s contrapuntal language, and in the Grosse Fugue or the Missa Solemnis, he provides the dense, multilayered textures and relentless development of subjects he encountered in Bach. Scholars like Robert Marshall have argued that “Beethoven’s late-period fascination with counterpoint stems directly from this Bachian foundation, making his arrangements more an act of creative assimilation than literal transcription.”

Raff/Bach

Raff/Bach: English Suite No. 3 in G Minor, BWV 808 (Capella Istropolitana; Jaroslav Krček, cond.)

The Swiss-German composer and teacher Joachim Raff (1822-1882) was famous for his symphonies, chamber music, and piano works. Highly popular during his lifetime, his music was subsequently overshadowed by the rise of composers like Richard Wagner and Johannes Brahms.

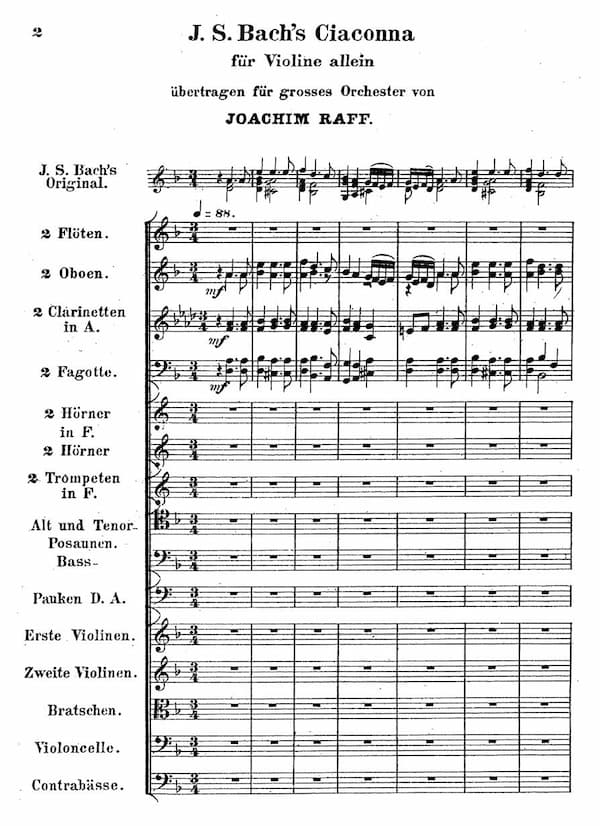

Raff/Bach: Chaconne

Raff was a prolific arranger who believed that some of Bach’s works, originally written for solo instruments, contained implicit orchestral textures. In 1873 he fashioned an orchestration of Bach’s Chaconne in D minor from the Partita No. 2 for Solo Violin. And one year later, he crafted an orchestral transcription of Bach’s English Suite No. 3 in G minor, BWV 808. These arrangements reflect his broader interest in making Bach’s music more accessible to 19th-century audiences.

His pioneering effort during the 19th-century Bach revival is scored for a modest orchestra, reflecting a Classical-Romantic balance that avoids the heavier orchestration of late Romanticism. Raff also streamlined the composition to five movements, excluding the second Gavotte and Gigue and focused on movements that he felt translated best to the orchestral medium.

Raff’s transcription is characterised by an acute sensitivity to Bach’s original intent. He avoids excessive Romantic embellishment, shunning all virtuosic flourishes. Instead, Raff emphasises the polyphonic textures and harmonic structure, distributing Bach’s keyboard lines across the orchestral sections to highlight implied counterpoint. This arrangement was part of Raff’s broader mission to bridge Baroque and Romantic aesthetics, making Bach’s music available beyond the niche of keyboard players and bringing the music into the concert hall.

Elgar/Bach

Elgar/Bach: Fantasy and Fugue in C minor BWV 537 (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

Sir Edward Elgar’s most notable effort with regard to orchestral transcriptions emerged in his re-imagining of Bach’s Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 537. Composed between 1921 and 1922, we find Bach imagined through the lens of a late Romantic orchestration. To be sure, the work reflects Elgar’s deep admiration for Bach, as well as his desire to make the music accessible to larger audiences via a modern symphony orchestra.

Elgar/Bach: Fantasy and Fugue in C minor BWV 537

Elgar’s transcription originated from a casual yet significant moment in 1920, when he dined with Richard Strauss. During their conversation, Strauss apparently suggested that Elgar try his hand at orchestrating a Bach fugue, a challenge Elgar took up with great enthusiasm. As he writes, “I wanted to show how gorgeous and great and brilliant Bach would have made himself sound if he had our means.”

Elgar’s transcription is not merely a technical exercise but a deeply personal reinterpretation reflecting his musical identity. While staying faithful to Bach’s thematic material and contrapuntal structure, he imbues the work with his signature lush harmonies and sweeping phrasing, reminiscent of his own compositions. His orchestration enhances the dynamic contrast and makes the emotional arc more pronounced.

Elgar’s use of orchestral colour, the warm tones of the strings and the poignant interjections by the woodwinds and the harp, bridges the gap between two distinct musical eras with sensitivity and flair. This fascinating fusion creates a dialogue between different sensibilities and offers a unique perspective on Bach’s timeless genius. It stands as a testament to Elgar’s reverence to the past and his innovative spirit, ensuring that Bach’s music would resonate anew in the concert halls of the 20th century.

Respighi/Bach

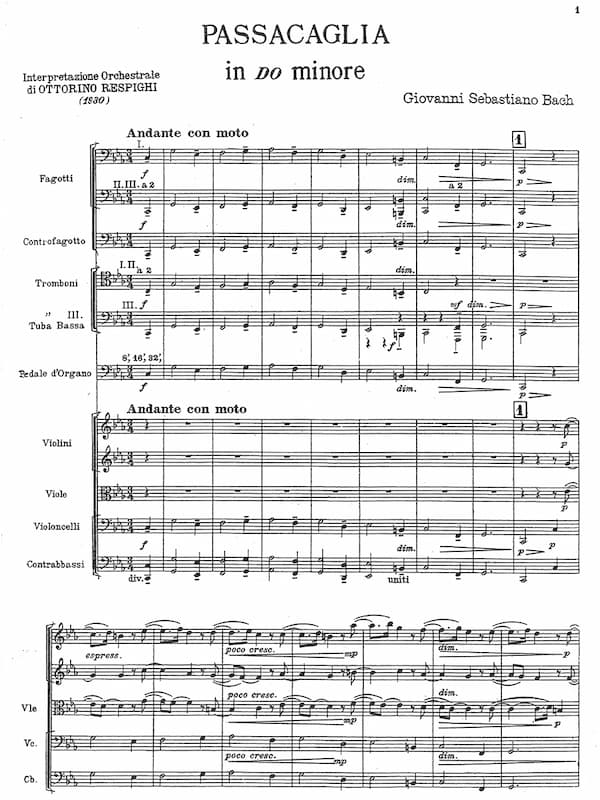

Respighi/Bach: Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor BWV 582 (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

As an avid musicologist, Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) was deeply influenced by his studies of early music. When Arturo Toscanini commissioned Respighi to create an orchestral transcription of Bach’s great Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, he was predictably delighted. Fritz Reiner had just premiered Respighi’s 1929 orchestrations of Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in D major, and Toscanini wanted something even more spectacular for his upcoming New York Philharmonic tour.

Respighi/Bach: Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor

The commission came at a time when Respighi’s reputation was at an all-time high in the United States. In addition, the early 20th century also saw a renewed interest in Bach’s music, partly fuelled by the Bach Revival and the advent of recording technology. To be sure, orchestral transcriptions made abundant use of expanded timbres and dynamics offered by modern symphony orchestras.

Respighi’s transcription was part of this wider movement, but his efforts stand out for its distinctly Italianate flair and bold orchestral choices, which contrasted with the more cinematic approach taken by Leopold Stokowski. Respighi retains the ostinato as the foundation, and his orchestration amplifies Bach’s dynamic contrast. As the variations unfold, Respighi introduces a kaleidoscope of orchestral colours while preserving the harmonic structure and intensifying the emotional arc.

Respighi’s orchestration of the fugue is a tour de force of imagination, blending Baroque rigor with Romantic exuberance. He retains Bach’s contrapuntal integrity but reframes it as a symphonic showpiece. It is a dialogue between Baroque and Romantic aesthetics, honouring Bach’s structural genius while infusing his own compositional voice. You might have noticed that Respighi’s reworking includes an organ as well.

Mahler/Bach

Mahler/Bach: Suite for Orchestra (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Riccardo Chailly, cond.)

Gustav Mahler participated in the prevailing trend of adapting Bach’s works for larger ensembles and making it palatable for modern audiences. His “Bach Suite” blends emotional intensity and orchestral richness, but it is less flamboyant than the Respighi or Elgar settings. It offers a more introspective take on Bach, revealing Mahler’s reverence for the past and his subtle imprint as a Romantic visionary.

Mahler’s “Bach Suite” emerged during a transitional period in his life. After resigning from the Vienna Opera in 1907 due to anti-Semitic pressure and personal tragedies, which included the death of his daughter Maria in the same year, Mahler took up his post in New York. The “Bach Suite” was likely prepared for performance with the New York Philharmonic, and it was eventually premiered in 1910 at Carnegie Hall.

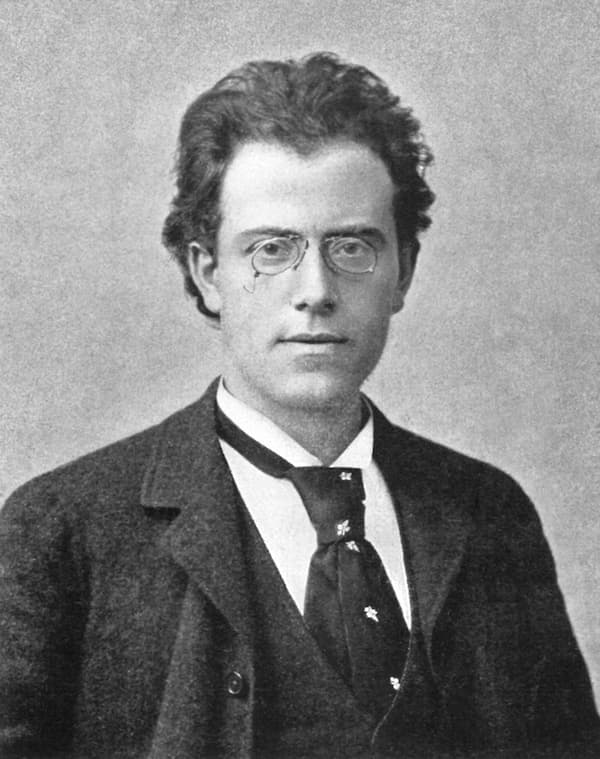

Gustav Mahler, 1892

The Mahler “Bach Suite” drawing four movements from the Bach’s Orchestral Suites, is reorchestrated for a large and modern orchestra and a continuo group featuring harpsichord and organ. Unlike Respighi or Stokowski, who added extravagant colours, Mahler’s approach is relatively conservative, aiming to enhance rather than transform Bach’s music. His orchestration amplifies the emotional weight and clarity of the original while adapting it to the capabilities of a late-Romantic ensemble.

In his stylistic synthesis, Mahler bridges Baroque and Romantic aesthetics with subtlety and respect. He avoids lavish embellishments, and instead focuses on clarity, balance, and emotional resonance. The inclusion of harpsichord and organ pays homage to Bach’s sound world, while the expanded orchestra reflects Mahler’s symphonic instincts. The “Bach Suite” is not a radical reinvention, but a practical yet personal interpretation of a seasoned conductor.

Schoenberg/Bach

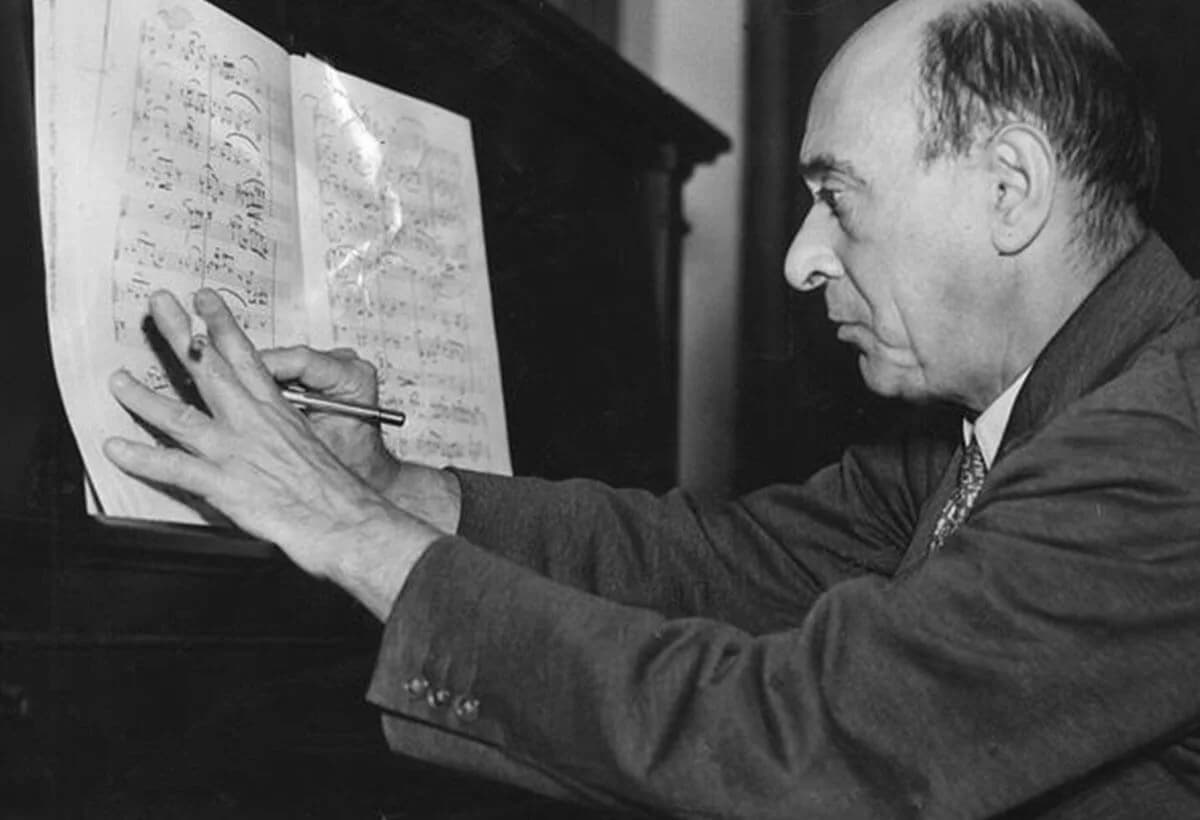

Arnold Schoenberg

The Austrian composer and pioneer Arnold Schoenberg demonstrated a deep engagement with the music of Johann Sebastian Bach through his orchestral transcriptions. Among his most significant arrangements is Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in E-flat Major, BWV 552 (St. Anne), completed in 1928. This re-working reflects Schoenberg’s reverence for Bach as a foundational figure in Western music as well as his desire to reinterpret his music through the lens of early 20th-century modernism.

Although the work is scored for a large orchestra including timpani, cymbals, triangle, and harp, Schoenberg’s transcription is characterised by clarity and timbral variety. With the pedal line reinforced by double basses, tuba, and timpani, Schoenberg creates a resonant foundation, and by including sharp dynamic contrasts, he heightens the prelude’s drama.

The fugue showcases Schoenberg’s ingenuity, particularly as he layers all three subjects with

kaleidoscopic orchestration, culminating in a thunderous climax with cymbals and timpani. Schoenberg avoids excessive embellishments, instead using orchestration to clarify Bach’s polyphonic structure. Yet, in the angularity of certain passages and the stark timbral contrasts we can already hear Schoenberg the modernist who introduced his own Variations Op. 31 in the same year. It is hardly coincidental that the Variations build on a recurring motive on Bach’s name.

Closing Thoughts

J.S. Bach

In the hands of great composers, arrangements of Johann Sebastian Bach’s keyboard music, Gustav Mahler included, represent a profound dialogue between Baroque genius and subsequent musical epochs. These works, though varied in scope and intent, share a common thread. They amplify Bach’s intricate counterpoint and intimate textures for broader audiences and breathe new life into pieces once confined to the harpsichord or fortepiano.

Far from mere historical curiosities, the featured arrangements reveal the adaptability and timelessness of Bach’s music. Each generation reinterpreted Bach’s legacy through a contemporary lens of social and cultural conventions, and through the intellectual and emotional filters of their own artistry. Yet, for every arrangement explored here, countless others remain unsung, a poignant reminder of the vast, uncharted tapestry of Bach’s musical legacy.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Schoenberg/Bach: Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major, BWV 552 (Boston Symphony Orchestra; Seiji Ozawa, cond.)

Very interesting. I particularly like the jazz Bach arranged and played by the Jacques Louissier Trio, and the Swingle Singers, in their first and best incarnation in the sixties,