The Piano Quartet genre has enticed and inspired many of history’s greatest composers. In my two previous blogs, we have truly listened to some incredible music, ranging from Mozart to Mahler and from Beethoven to Bartók. We are always so grateful to receive your expert comments and also look forward to hearing your suggestions again.

As with other chamber music genres featuring the piano, the piano quartet is one of the most popular groups, attractive to amateur and professional performers. Because of the limited size of the performing group, it is always intimate music suited to the expression of subtle and refined musical ideas.

As a scholar wrote, “rich displays of varied instrumental colour, and striking effects produced by sheer sonority, play little part in works for piano quartet. In place of those effects are refinement, economy or resources, and flawless acoustical balance.” By popular request, let’s explore some fantastic bonus repertoire for piano quartet, starting once more with Johannes Brahms.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet No. 2 in A Major, Op. 26

In all, Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) composed three piano quartets. And it was in November 1862 that Brahms introduced his new Piano Quartet in A Major, Op. 26 to the public. Brahms himself was the pianist, and he was supported by members of the famous Joseph Hellmesberger Quartet. The A-Major piano quartet soon became one of the composer’s most frequently performed works, but interestingly, that work fell out of favour in the twentieth century. Performers and audiences preferred the fiery Op. 25, and according to an annotator, “the A Major Quartet is now one of Brahms’ most neglected major works.”

The reason might well be located in the broad, one might almost say, symphonic scale of the work. Three of the four movements are in expansive sonata forms, and the work is far more poised and lyrical than the exciting G minor. As has been observed, “the work’s melodic richness is only one of its strengths, and the gypsy energy of the G minor is still felt.”

Johannes Brahms’ Piano Quartet, Op. 26

The work features the characteristic bold keyboard style of Brahms, and while Beethoven features in the formal design, the lyrical passages are surely inspired by Franz Schubert. Just listen to the opening of the first movement. The piano opens with a floating gesture in gentle triplets and regular eight notes, and it is met by the cello with an important and frequently used scale figure. This gentle lyricism soon gives rise to a most powerful outburst, reshaping the theme into a rather muscular profile. The slow movement is one of the most glorious that Brahms ever conceived, while the central part of the Scherzo and the Finale sound plenty of Hungarian colouring.

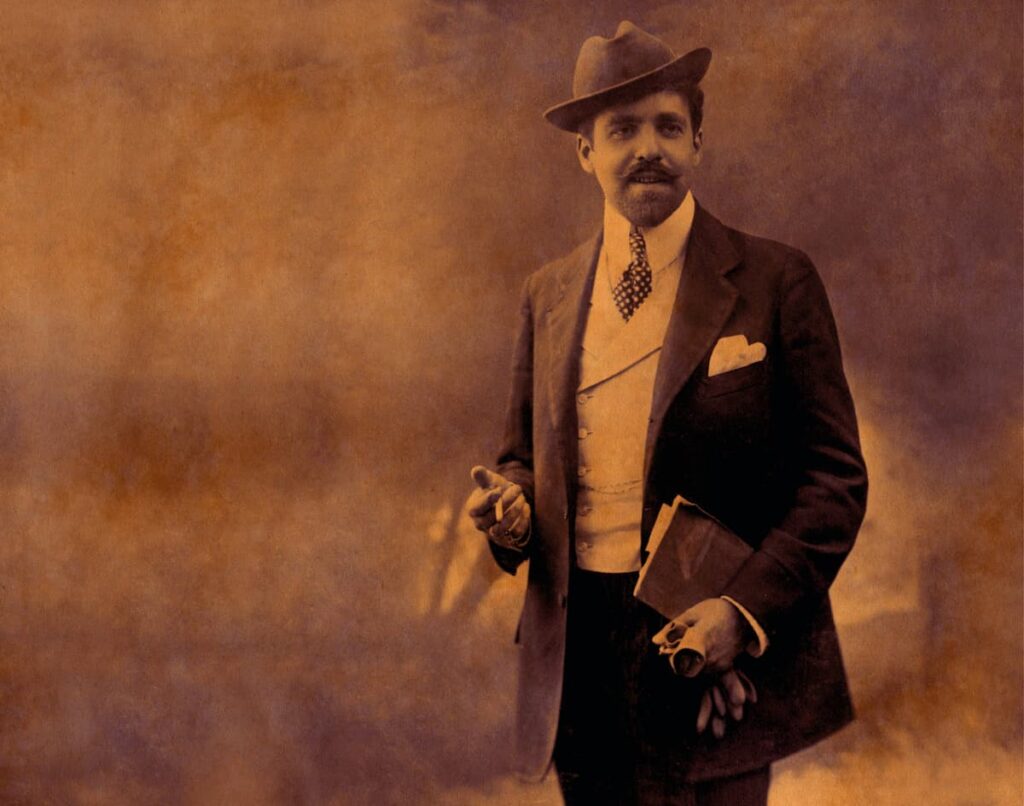

Reynaldo Hahn: Piano Quartet No. 3 in G Major

© bru-zane.com

Reynaldo Hahn: Piano Quartet No. 3 in G Major (Room-Music)

Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) was born the youngest of twelve children in Caracas, Venezuela. Yet by the age of three, the family had moved to Paris, and the highly talented boy was soon invited to sing operetta numbers while accompanying himself on the piano. Hahn entered the Paris Conservatoire at the age of eleven, and he was taught by Massenet who also introduced him to the publishers Heugel.

As a conductor, Hahn was known for his sensitive interpretations of Mozart, and his musical tastes ranged from Palestrina to Haydn and Ravel. Surprisingly, he absolutely hated the music of Debussy but was fond of Wagner. His favourite composer was surely Robert Schuman. As he writes, “There is no emotion that he has not experienced: all the phenomena of nature are familiar to him, and he has known them all and can impart to us the thousand-and-one emotions associated with them.”

Hahn’s music is delightfully uncomplicated, and it communicates radiant freshness. It certainly is very direct and comfortably eclectic, “sometimes unashamedly retrospective.” The opening “Allegro” of his G-Major piano quartet opens with a graceful subject before adopting an impassioned character. The charming “Andante” is interrupted by a stern central passage, while the “Allegro” leads the work to a graceful and compelling conclusion.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, K. 478

A good many writers and scholars consider Mozart’s Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, K. 478, the first major piece composed for piano quartet in the chamber music repertoire. It was actually commissioned by the publisher Franz Anton Hoffmeister, who was looking for ensemble music that also included the viola. Mozart, of course, loved that instrument when he himself performed chamber music.

Hoffmeister ordered three piano quartets, but after he received the first piece, he cancelled the order. He had intended the compositions for the Viennese amateur market, but Mozart had not. A scholar writes, “the technical demands on the performers, not to mention the complexity of the music itself, resulted in poor sales.” An article in a Weimar musical journal concluded, “this work as performed by amateurs could not please.”

Mozart’s Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, K. 478

Everybody yawned with boredom over the incomprehensible tintamarre of 4 instruments, which did not keep together for four bars on end, and whose senseless concentus never allowed any unity of feeling; but it had to please, it had to be praised! What a difference when this much-advertised work of art is performed with the highest degree of accuracy by four skilled musicians who have studied it carefully. In his day, Mozart was perceived as a highly talented composer who wrote very difficult music, and I would add that in his minor compositions, Mozart shows his deeply human side.

Max Reger: Piano Quartet in D minor, Op. 113

Max Reger

Max Reger: Piano Quartet in D minor, Op. 113 (Aperto Piano Quartet)

Chamber music was always important to Max Reger (1873-1916). His Opus 1 is a Violin Sonata, and his Op. 146, written shortly before his death, a Clarinet Quintet. Reger was an outstanding pianist, and we can find chamber music with piano throughout his career. And his highly complicated piano parts were clearly written for his exceptional abilities at the keyboard.

Reger, who was teaching composition in Leipzig, was preparing for a performance of Brahms’ Op. 60 in November 1909. As such, he decided to write his own piano quartet in D minor, Op. 113. Before he had even written the piece, Reger scheduled it for performance at a Festival in Zurich, a yearly meeting place for contemporary music. Reger barely managed to finish the work, and he performed the premiere by reading straight from the manuscript.

When someone asked for an introduction to the piece, Reger ironically replied, “The work, naturally, has four movements which can be accounted for by my prolificity. The Larghetto (third movement) proceeds quite slowly; according to ancient custom, one should take the other three movements faster, of course. Yet one could play it the other way round, in which case this music would sound even worse! The tonality is D minor – for which is an extremely daring claim, I accept no guarantee. There is no point in listing the themes, for these would never be heard. A worthy police force could not fail to notice that even in this work – as unfortunately, I have already done so often – I have stolen, completely shamelessly.”

Johanna Senfter

Johanna Senfter

Johanna Senfter: Piano Quartet in E minor, Op. 11 (Else Ensemble)

As I mentioned, Max Reger taught theory and composition at the Conservatory of Leipzig. A substantial number of highly talented musicians passed through his hands, however, he regarded Johanna Senfter (1879-1961) as his most accomplished student. As he wrote to her father, “Considering your daughter’s remarkable musical and compositional aptitude… it would be a sin not to fully nurture her potential.”

Senfter won the Arthur Nikisch prize for composition in 1910, and as one of the most prolific female composers of the 20th century, composed over 130 vocal and instrumental works. Her early works predictably drew inspiration from Reger, but Senfter had a real talent for melodic innovation and creating independent compositional structures. Senfter was a very reclusive, shy and modest artist who dedicated her life solely to music. Prejudices against female composers also denied her some opportunities in the field, and she later stated, “If I weren’t a woman, I would have it easier.”

Senfter composed her E-minor piano quartet, Op. 11, roughly in 1911. She must have been a fabulous pianist, as her piano writing is resoundingly rich, and the strings almost take on an orchestral quality. The opening movement juxtaposes an archaic harmonic language with Romantic timbres, and the three-part song from the second movement produces delicate Impressionist textures contrasted by impressions from Brahms. A gentle variation movement brings us to a “Finale” that returns to the grandeur of the opening.

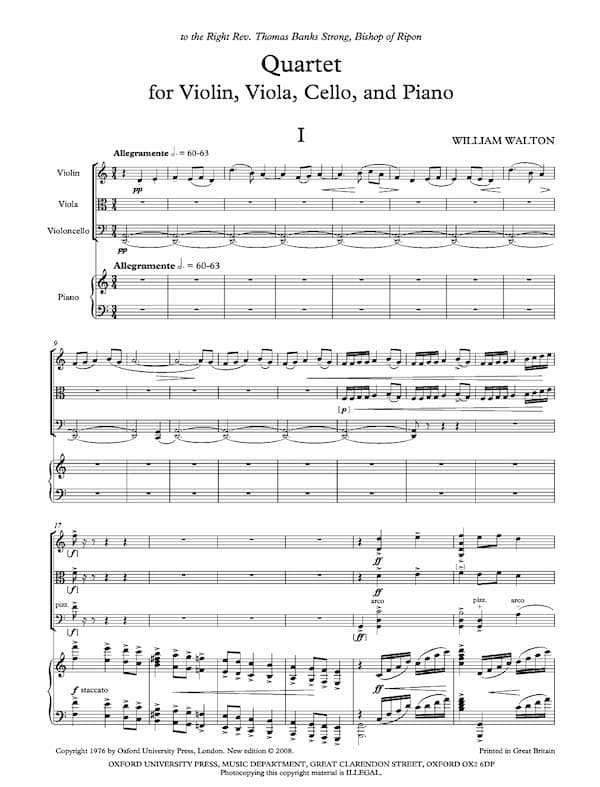

William Walton: Piano Quartet

William Walton’s Piano Quartet

William Walton: Piano Quartet (Matthew Jones, violin; Sarah-Jane Bradley, viola; Tim Lowe, cello; Annabel Thwaite, piano)

William Walton (1902-1983) grew up playing the violin with very little success. However, he credited the violin for being useful for the study of ear training. As he later explained, “I could never organise my fingers, and it sounded so awful.” By all accounts, Walton’s piano skills weren’t much better, but that did not prevent him from starting work on a Piano Quartet in 1918.

Walton was only 16 and studying at Oxford’s Christ Church choir school, and he wrote home glowing letters about his studies of the music of Debussy, Ravel, and even Schoenberg. According to an annotator, the primary stimulus, however, was his meeting with Herbert Howells. Howells was significantly older, and he was being grandly celebrated for his piano quartet.

The piano quartet was completed in 1919 and much revised, and we unmistakably hear the influences of Vaughan Williams, Ireland, Bridge, Brahms, and Ravel. The London premiere was a rather mixed bag, but scholars did note the “rhythmic drive and Elgarian melodies of the second movement, the lack of direct repetition of themes, the composer’s first fugue, and the melancholic lyricism of the third movement.” Mind you, Walton described the piece as his “first composition to show any kind of talent; it was written when I was a drooling baby, but it is a very attractive piece.”

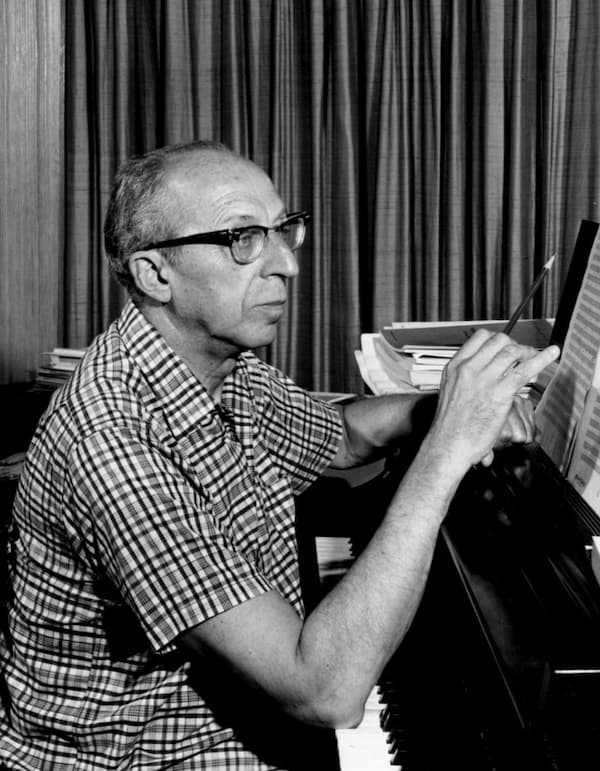

Aaron Copland: Piano Quartet

Aaron Copland, 1962

Aaron Copland: Piano Quartet (Boston Symphony Chamber Players)

In his piano quartet dating from 1950, Aaron Copland (1900-1990) explored a much different soundscape. The composer was always interested in exploring various methods of composition, and maybe it is not surprising that he would turn to serialism. As he once said, “composing with all twelve notes of the chromatic scale can give one a feeling of freedom. It’s like looking at a picture from a different point of view.”

However, as the composer freely admitted, he never strictly kept to the rules of serialism, and there always seems to be a tense tonal centre in the piano quartet. Scored in 3 movements, the opening is a slow fugue that seems like a meditation on the late Beethoven. The dramatic narrative, according to Kai Christiansen, “lies in the fugue’s sectional development, which is modern, yet surprisingly classical and projects a serialism that seems almost tonal.”

Jazz influences appear in the central “Scherzo,” as Copland just loves spiky rhythms and sharp pointillism. Can you hear the song “Three Blind Mice” at the opening of the “Finale?” These three notes stay recognisable throughout, and according to critics “develop a modern method accommodated by populist touches.”

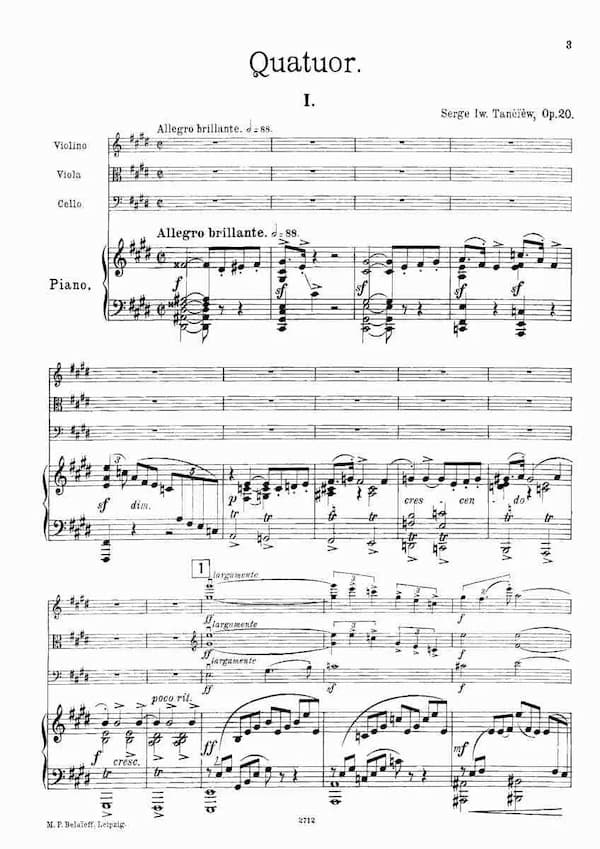

Sergei Taneyev: Piano Quartet in E Major, Op. 20

Sergei Taneyev’s Piano Quartet, Op. 20

Described as “The Russian Brahms,” Sergei Taneyev (1856-1915) has three large-scale chamber works with piano in his catalogue. All three date from the late stages of his career and almost excessively focus on musical architecture. As the composer explained, “It often happens that a musical idea buzzing in my mind will attract my special attention. At this stage, it is already obvious that it will form the main idea of the work… A long time later, sometimes even a matter of years, the idea may recur. In most of my works, the movements are linked together with common thematic material so that they mutually reflect each other when the work is elaborated.”

The piano quartet was completed in 1906 and scored in three substantial movements. It shows that the composer was a master of melody, counterpoint, structure, and use of the chamber ensemble. If you want to understand the “Russian Brahms” statement, all you have to do is listen to the shimmering, colourful, and orchestral sounds of the opening movement. Perfect structure, perfect form but full of emotions. The second movement does invoke Tchaikovsky, sounding sweet and memorable melodies full of bitter-sweet tenderness. And just listen to the Brahmsian counterpoint and rigorous developments in the “Finale.”

I really hope you enjoyed these piano quartet selections, and I am happy to announce that you can look forward to a number of blogs on the piano quintet coming up soon.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter