Operas, Concertos, Oratorios, Cantatas & More

Baroque musicians

I know this is absolutely subjective, but for me personally, the Baroque music period produced some of the most intense, dramatic, devotional, appealing, and simply most beautiful music imaginable. In school, we are all told that the Baroque music period falls between the years 1600 and 1750. “Baroque” is a very general and relatively recent term adopted for this historical period. And while no era starts and ends at the stroke of midnight, the bookmark years do designate important signposts.

Johann Sebastian Bach

The year 1600 was abuzz with discussions about “the new music,” and with paving the way for what was probably the most important musical achievement of the Baroque era; the invention of opera. The year 1750 meanwhile, marks the death of Johann Sebastian Bach, an unbelievable genius composer who “was able to survey and bring together the principal styles, forms, and national traditions that had developed during preceding generations and, by virtue of his synthesis, enriched them all.” For many professionals and listeners, myself included, Bach was the greatest composer of all time. I don’t know if you agree with me or not, but the roughly 150 years of the Baroque era brought us vocal music of great dramatic power and religious devotion, alongside the rise of instrumental sonatas, concertos, and collection of dances. There is so much to explore, so here is a little survey of the best in baroque music.

Claudio Monteverdi: L’incoronazione die Poppea, “Pur ti miro”

Giulio Caccini

When we are talking about the best and most original musical ideas flowing from the baroque era, opera must be the logical starting point. It all started in Florence, Italy, with a group of writers, artists, and musicians who suggested that music must heighten the emotional power of the text. The composer Giulio Caccini writes, “the imitation of the meaning of the words must seek out more or less passionate chords.” This kind of emotional style—I think they called it representational style—consists of a melody that freely moves over a foundation of very simple chords.

Berndardo Strozzi: Claudio Monteverdi (ca. 1630)

It was perfect for expressing the meaning of a short text, like a poem, but they soon decided that it could be applied to an entire drama. And that was the very short version of how opera came into existence. In no time the opera concept included recitatives to advance the plot and action, great lyrical and highly emotional arias, and various ensembles projected against lavish spectacles and scenic displays. Just listen to how Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) uses dissonance and instrumental color to create drama, expressiveness, atmosphere, and suspense. And as you can hear in the featured excerpt, the “father of opera” Monteverdi is responsible for establishing the love duet as a central component of opera.

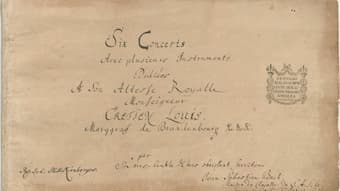

Johann Sebastian Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047

Brandenburg Concerto title page

In Baroque music, the contrast was an essential element of expression, as was unity. At first glance, this doesn’t make much sense unless we remember one of the most-beloved inventions of the Baroque era, the concerto. Baroque music composers essentially invented two different types, the concerto for solo instruments and an accompanying instrumental group. The other type is called “Concerto grosso,” and it features the contrast between a small group of instruments and a larger group. At the end of the Baroque, the Concerto Grosso featured three movements and it was described as “the fire and fury of the Italian style.” Today it might be called cultural appropriation, but the concerto style spread like wildfire across Europe, and it found its way into the hands of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). In the 2nd Brandenburg Concerto, really my all-time favorite—the solo group consists of trumpet, recorder, oboe, and violin, basically instruments in the higher register. The larger group includes first and second violins, violas, and double basses, with the basso continuo—I tell you later what that means—played by cello and harpsichord. It is one of the most glorious examples of baroque music, and it beautifully captures the spirit of the times.

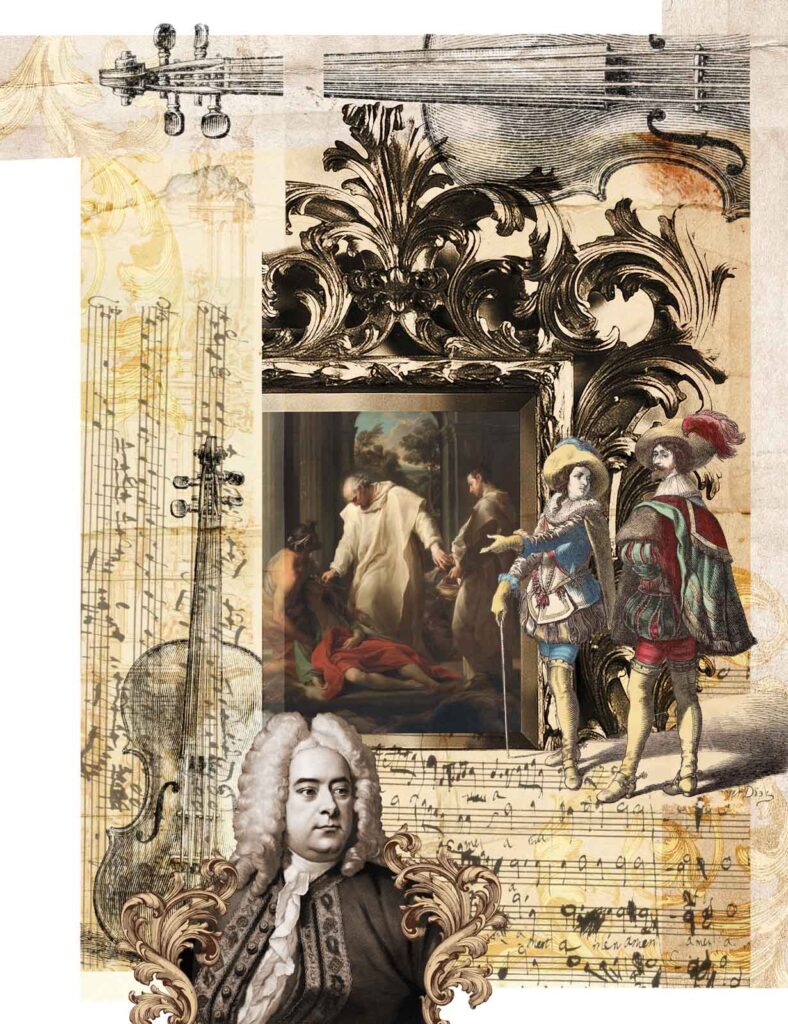

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, “Hallelujah Chorus”

A Baroque church in Germany

Oratorios are choral dramas that “embody the splendor of the Baroque, with their soaring arias, dramatic recitatives, grandiose fugues, and majestic choruses.” From that description it sounds like opera, however, there is one essential difference between opera and the oratorio; the oratorio is not staged. It was a decision made by the church fathers, as the Catholic Church strictly forbade staged musical theater during Lenten season, as this period of fasting and prayer supposedly prepares believers for the celebration of Easter.

George Frideric Handel

Fasting and preparing aside, audiences still wanted to hear operatic music, so composers started to write plays featuring sacred dialogues and narrative meditations. Generally based on a biblical story, the action was described with the help of a narrator in a series of recitatives and arias. And it was all very clever because these “Oratorios” contained all the musical elements of opera but were not considered musical theatre; they operated strictly as concert pieces. George Friedrich Händel (1685-1759) composed his most popular oratorio Messiah in 1741. The libretto is subdivided into three parts, and the famous “Hallelujah chorus” concludes the second part, which highlights the Passion and Resurrection of Christ. The emotional impact of the music is breathtaking, and Händel clearly composed some of the best baroque music, ever.

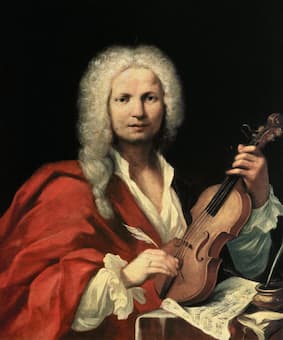

Antonio Vivaldi: Four Seasons, “Spring”

Antonio Vivaldi © art-prints-on-demand.com

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) was known as the “Red Priest,” and he is probably most famous for his concertos. That’s hardly surprising, as being a violinist, he composed well over 500 concertos. This format, featuring a soloist against an accompanying instrumental group, lent itself beautifully for experiments in sonority and virtuoso playing. Predictably, the violin was Vivaldi’s solo instrument of choice, and together with many colleagues, he was responsible for emancipating instruments “from their earlier dependence on vocal music.” Vivaldi takes all the delicious and expressive devices that are used to describe the emotions in early opera and transplants them into the instrumental realm. Vivaldi is certainly best-known for The Four Seasons, a group of four violin concertos. But it is not all that easy to clearly assign emotions and drama to music without a text. To make sure that performers and audiences understood what was going on in the music, Vivaldi accompanied each concerto with a poem. Mind you, he probably wrote his own poetry as well. Each line of the poem was printed above a certain passage, and the music attempted to mirror the action or meaning described. How brilliant is that! The so-called “father of the concerto” basically established program music, and he also codified the 3-movement form for solo concertos. And just listen to the delightful instrumental refrains, in our excerpt all played by baroque period instruments.

Barbara Strozzi: Begli occhi

A lutenist in the 17th century

I looked it up in a dictionary, and the Italian word “cantare” basically means, “to sing.” That particular word became the basis of a genre of music that employs one or more solo vocalists with instrumental accompaniment, and it was called the “Cantata.” The early forms of cantatas were secular and based on one of three poetic genres. The lyrical kind expressed personal emotion and allowed the music to dominate the story; the dramatic kind is written for performances in a comedy or tragedy, and the narrative kind of poem tells a story following characters through a plot. One of the most important figures in this genre was the singer Barbara Strozzi.

Barbara Strozzi

She might have been a courtesan—a highly cultured woman entertaining men, and she absolutely possessed the artistic skills of this particular profession. She was a famous singer, played the lute, and she even wrote her own poetry. Her contemporaries highly praised her musical talents, and her voice was “compared to the harmonies of the spheres.” In the event, Barbara Strozzi was a unique figure during the early Baroque era, as women “were either portrayed as either saints or sinners, pictures of purity or wickedness.” And composing was clearly in the male domain. However, Barbara Strozzi not only composed, she also published many of her own compositions. In the featured secular cantata we find many abrupt tempi and mood changes. The sung dialogue between the two voices tells of the bitterness of unrequited love, which we can clearly hear in the harsh dissonances. This kind of expressive power belongs to the best music the baroque has to offer.

Arcangelo Corelli: Trio Sonata in D Major, Op. 3, No. 2

Arcangelo Corelli

The Baroque era is famous for the emancipation of instrumental music. For the first time, instrumental music was considered as important as vocal. That also means that new instruments were developed while old instruments were perfected. And in the instrumental music of Italy, the violin reigned supreme. And it was in the city of Cremona that we found the most famous violin maker, with names we still easily recognize today. Nicolò Amati, Antonio Stradivari, and Giuseppe Guarneri initiated a golden age of string music in Italy. While the famed instrument makers had their home in Cremona, it was the city of Bologna that became the center of violin playing. And the name primarily associated with Bologna was the composer and violinist Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713).

A trio sonata ensemble

He became one of the most popular composers in the most popular form of chamber music, the so-called “sonata.” His favorite instrumental combination involved two violins and a basso continuo. This kind of music was printed on three staves, and hence became known as “Trio sonatas.” But it actually takes four performers, as the basso continuo simultaneously plays the bass line by a cello or bassoon, and a harpsichord or organist realizes the indicated harmony. The “Trio Sonata” generally sported four movements, alternating slow-fast-slow-fast, and the delicious modulations in seemingly endless sequences became a much-beloved feature of music in general.

François Couperin: Troisième leçon de ténèbres

François Couperin

As you can tell, Italy was dominating the music and cultural scene during much of the Baroque era. However, there was original music composed in other parts of Europe as well. French composers also cultivated instrumental music, but they tended to favour more intimate and courtly genres. “French taste also relished lavish ballets and a distinct style of opera, and they had a vigorous church music tradition.” A particularly vibrant form of church music was celebrated on the three days before Easter. Called the “Tenebrae” services—from the Latin word for “darkness,” François Couperin (1693-1733) composed one of the greatest works in all of Baroque music. His Tenebrae Lessons combine French and Italian musical tastes. “From Italy came the intensity of expression, and aria style of singing, and from the French background a highly refined delicacy and highly ornamented melodic line.” As Couperin writes, “The Italian taste and the French taste have long been separate in the domain of music. I have always valued things that are worthy of value, regardless of author or nationality.”

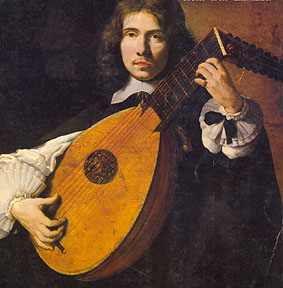

Denis Gaultier: Le tombeau de Monsieur de l’Enclos (Allemande)

The Baroque dance

I just love to dance, and playing music to accompany dances has always been an important activity for instrumentalists and performers. In Baroque music, various social dances began to separate from the dance itself and became a type of independent instrumental music. However, “the connection of such music to the original dances remained strong, as it influenced tempo, meter, character, and form.” The title of a dance was usually taken from the social dance the music sought to imitate. They tended to refer to characteristic dance steps like the “Saltarello” (from the Italian saltare, to jump,) or suggest geographic origins, such as the “Allemande” or French for German. Once a number of dances had been linked together, a new genre the “Suite” came into existence. The exact content of suites varied greatly, but often include a common sequence of allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue. The two favorite instruments for dance music were the harpsichord and the lute. I personally can’t get enough of lute performances, as the subtlety of tone and the phrasing actually forces me to learn how to listen all over again. In time, “Suites” became incredibly popular and were performed by virtually all instruments, including orchestras and chamber ensembles.

Henry Purcell: Dido and Aeneas, “Dido’s Lament”

Dido and Aeneas

For all intents and purposes, Henry Purcell’s (1659-1695) opera Dido and Aeneas might easily have become a blueprint for the continuous and lasting presence of English Opera. Crudely based on Virgil’s Aeneid, librettist Nahum Tate even included popular elements of Baroque opera, including a hunt, a sorceress and a storm. The musical score only features four principal roles, with the orchestra reduced to strings and continuo. The prologue is quickly followed by three brief acts, and the entire opera—including dances and choruses—barely lasts sixty minutes. Despite its brevity, this opera in miniature exhibits a wide range of emotional content. And it certainly reflects both the “achievements of English theater music and continental operatic influences.” Unfortunately, no English composer in the following two centuries would develop and maintain Purcell’s recipe for a distinctive and genuine national operatic tradition, as the music scene in London went wild for Italian opera.

Collage of music and arts in the Baroque period by Stephen Louis © Cathay Pacific

The baroque era was a time of turbulent changes in politics, science, and the arts. It fought horrible wars alongside political and religious lines, but it was culturally international. National musical styles, as we have seen and heard, did exist, but all without nationalism. In fact, in terms of music and the arts, there was a free interchange among national cultures. As a historian writes, “The sensuous beauty of Italian melody, the pointed precision of French dance rhythm, the luxuriance of German polyphony, and the freshness of English chorale singing, all nourished an all-European art that absorbed the best of each national style. Paired with a vivid interest in remote cultures and exotic locales, this incredible period in Western cultural history produced music that flowed easily across national boundaries.” With all the political nonsense going on in 2022, I do feel that we must once again demand a free global exchange of musical and artistic ideas; or at least have the communicative and scholarly freedom that allows for that possibility.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter