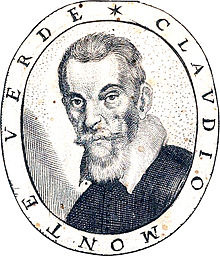

Creator of modern music

In 2017 we celebrate the 450th birthday of Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643). He was the most important musician in late 16th and early 17th-century Italy, and the first great composer of opera. He developed powerful ways of expressing and structuring musical drama, and he is frequently hailed as the “creator of modern music.” Composing in nearly all the major genres of the period, Monteverdi instigated a paradigm shift in musical thinking that bid farewell to the late Renaissance and ushered in the artistic expressions of the early Baroque.

In 2017 we celebrate the 450th birthday of Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643). He was the most important musician in late 16th and early 17th-century Italy, and the first great composer of opera. He developed powerful ways of expressing and structuring musical drama, and he is frequently hailed as the “creator of modern music.” Composing in nearly all the major genres of the period, Monteverdi instigated a paradigm shift in musical thinking that bid farewell to the late Renaissance and ushered in the artistic expressions of the early Baroque.

Born in Cremona, Monteverdi had precocious musical talents and published his first collection of sacred music at the age of 15 with a prominent Venetian publishing house. Private lessons with Mark Antonio Ingegneri provided careful training in counterpoint and text setting, and 2 books of five-voice madrigals established his reputation outside his provincial hometown. To complement his musical portfolio he became an accomplished singer and instrumentalist, and was eventually appointed to the court of Duke Gonzaga of Mantua. Although employed in an entry-level position, a deliberate and selective publishing strategy significantly increased his reputation. His compositions were soon known in Venice, Florence, Nuremberg, Copenhagen and Ferrara, and elicited scathing criticism from the Bolognese conservative music theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi. His 1600 treatise On the imperfection of modern music cited Monteverdi’s use of irregular dissonances and modal treatment as examples of modern musical decadence. And when Monteverdi responded with his fifth book of madrigals, claiming in the preface that “music must serve the text by whatever means necessary,” it set in motion a raging debate that reverberated well into the middle of the seventeenth century.

Commissioned for the 1606-7 Carnival season, Monteverdi’s first opera L’Orfeo was performed in Mantua on 24 February 1607. This score of great dramatic power and lively orchestration was highly praised and published in Venice in 1609, with performances recorded in Salzburg in 1614 and 1619. His first 4 books of Madrigals were reprinted, and Arianna’s lament, the only section of his 1608 opera L’Arianna to survive, was said to have moved the audience to tears. Yet, the death of his wife and internal squabbles at court—including competition from the young Florentine composer Marco da Gagliano—made life in Mantua increasingly uncomfortable. Monteverdi embarked on a series of journeys, including a trip to Rome to present the publication of his Missa… ac vespere to its dedicatee, Pope Paul V. Monteverdi’s loyalty to the Gonzaga family was questioned, and he was unceremoniously fired in 1612. It took him almost a year to find a new job, but he was finally appointed maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s in Venice in the autumn of 1613.

Monteverdi celebrated his new position with his sixth book of madrigals, followed by a number of liturgical compositions for various Venetian churches. He maintained contacts throughout Italy, and provided musical commissions for Mantua, Florence, Bologna, and Modena alongside cultivating several Venetian patrons. Monteverdi had settled into comfortable middle age when a Mantuan delegation unwittingly infecting the city with the plague; by 1631 almost 50,000 inhabitants had perished. Commissions from Mantua and elsewhere dried up, and Monteverdi entered the priesthood on 16 April 1632. However, when the composer was approaching his 70th birthday, Venice established a number of public opera houses, and Monteverdi’s operatic career was revived. He composed his two last masterpieces, The Return of Ulysses in 1641 and The Coronation of Poppea in 1642. Significantly, these works contain tragic, romantic and comic scenes, and feature a more realistic portrayal of the characters. “The aim of all good music,” Monteverdi wrote, “is to affect the soul.” Monteverdi died in Venice on 29 November 1643 and his music was copied extensively into European and English manuscripts. His influence on later Baroque composers and all subsequent forms of musical expression was clearly considerable.

Monteverdi celebrated his new position with his sixth book of madrigals, followed by a number of liturgical compositions for various Venetian churches. He maintained contacts throughout Italy, and provided musical commissions for Mantua, Florence, Bologna, and Modena alongside cultivating several Venetian patrons. Monteverdi had settled into comfortable middle age when a Mantuan delegation unwittingly infecting the city with the plague; by 1631 almost 50,000 inhabitants had perished. Commissions from Mantua and elsewhere dried up, and Monteverdi entered the priesthood on 16 April 1632. However, when the composer was approaching his 70th birthday, Venice established a number of public opera houses, and Monteverdi’s operatic career was revived. He composed his two last masterpieces, The Return of Ulysses in 1641 and The Coronation of Poppea in 1642. Significantly, these works contain tragic, romantic and comic scenes, and feature a more realistic portrayal of the characters. “The aim of all good music,” Monteverdi wrote, “is to affect the soul.” Monteverdi died in Venice on 29 November 1643 and his music was copied extensively into European and English manuscripts. His influence on later Baroque composers and all subsequent forms of musical expression was clearly considerable.

Claudio Monteverdi: “Cruda Amarilli”

More Composers

-

Pierre Rode “He moved those without understanding to mindless admiration”

Pierre Rode “He moved those without understanding to mindless admiration” -

Niccolò Jommelli “The music is beautiful, but too clever and old fashioned for the theatre”

Niccolò Jommelli “The music is beautiful, but too clever and old fashioned for the theatre” -

Arnold Schoenberg “Great art presupposes the alert mind of the educated listener”

Arnold Schoenberg “Great art presupposes the alert mind of the educated listener” -

Richard Strauss “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I AM a first-class second-rate composer!”

Richard Strauss “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I AM a first-class second-rate composer!”