French Impressionism Artworks © The Art Story

The following article is the first of a three-part series on impressionism around the world; in France, in Europe and in our Modern World. In these articles, I explore the genre of impressionism. Born in France, it is known to have revolutionised the music world by breaking from over two centuries of traditions, rules and rigorous structures. While not presenting itself as better, it has provided many artists with an alternative and a new way of thoughts, free from boundaries and aiming towards exploration and development. As it grew from its native Paris to Europe and then the rest of the world, impressionism morphed into many different genres and explored new creative routes. Atonality would have never existed without it, nor would modernism or minimalism. Today, it is studied in music conservatoires — contradictory, that is where it was distancing itself from — and the works of Debussy are just as important as the ones of Bach.

French classical music is often perceived and limited to French impressionism — everyone seems to know about Debussy, Ravel or Satie only. It is very much true that impressionism was born in France, but it takes its roots many decades back with the music of Wagner, Berlioz, Liszt, or Chopin and to some extent the descriptive music of baroque composers such as Couperin, Rameau or Vivaldi. It is the association of these elements; the natural descriptions of baroque music and the harmonic and melodic progresses of late-romantic music, which in addition to a wish to break from tradition resulted in impressionism. The genre has allowed French music to grow a universal reputation, a true national identity, distinct from the rest of the world, and of course well associated with visual arts — particularly painting, but also a rupture from its past.

It is therefore quite understandable that impressionism is often perceived as being mostly French. And French only. But this is evidently untrue and shall dive into the matter of the subject in a subsequent article.

Maurice Ravel: Rapsodie espagnole (Lyon National Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

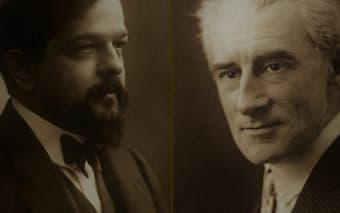

Debussy and Ravel are among the pioneers of Impressionism © juanrezzuto.com

At its birth, French impressionism shook the world. It was a rupture from two centuries of Germanic tradition; the totalitarianism of the relationship between tonic and dominant, tension and resolution collapsed. With impressionism, it was less about movement and direction, and more about colours and effects. The expression was not favoured by its composers and came out of critics who would compare the music to the one of painters; Cézanne, Degas, Manet, Monet etc. Debussy preferred the term symbolism.

Impressionism is at its origin born in the mind of Satie, although it is Debussy, then Ravel which are the ones that made it so popular and successful. Of course, all were influenced by each other. These composers would borrow harmonies from almost everywhere around the world — including Indonesia or North America —, as well as in popular music and even early jazz; it has been said of Debussy that he liberated tonality and harmony. While Debussy and Ravel find many common grounds, Satie is often perceived as the mauvais garçon of impressionism, and at times, he might be closer to Mussorgsky than his French counterparts. In my opinion, he is quite unique.

Erik Satie: Gymnopédies

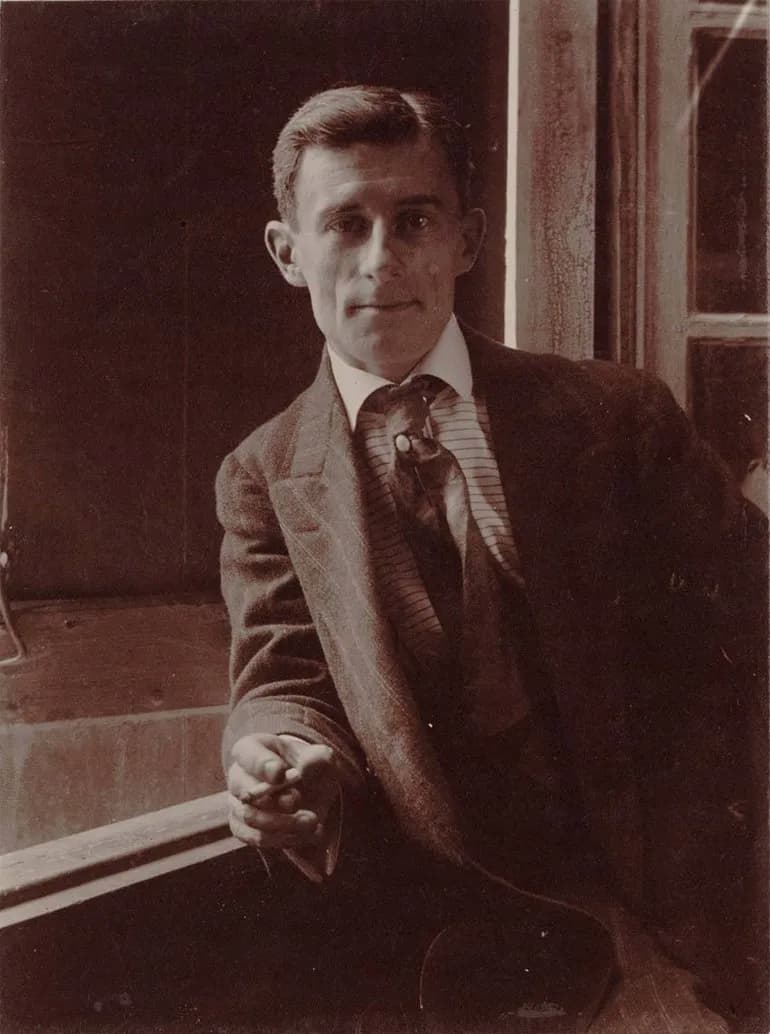

Satie with Claude Debussy in Debussy’s home, June 1911, photographed by Igor Stravinsky. © Wikipedia

It feels of importance to notice that contrary to other musical movements — such as baroque or classical — the term impressionism was coined after a wish to describe the composer’s creative intentions, and not the end result. What can be understood as impressionism or symbolism is the wish to convey sensations, ideas, effects, impressions rather than to describe in an accurate manner musical facts. Compositionally, this has been done through research for new colours — in music this translates as unusual scales or unorthodox rhythms for instance — and a rupture from convention — particularly in the structures. Altogether, impressionism sounds very different, from one artist to the other. In other words, whoever enjoys Debussy might not be fond of Satie, as they sound very different from each other. It is less the case with someone who enjoys Chopin or Liszt, Mozart or Haydn.

Impressionism in music — just like its equivalent in painting — has been hugely influential on everything that has followed. By breaking from the Germanic tradition and daring not to follow its strict well-established rules present in so much of the classical music written over the centuries, Debussy broke all the rules of music. And so did the ones that followed after, not only in France, but all around the world. After impressionism, everything was less about rules, traditions, accuracy and respect, but liberation, exploration, enjoyment and… impressions!

In the second article of this series on impressionism around the world, we will look at the lesser impressionists; a selection of composers that have written impressionistic music, outside of France, and have often been deprived of their recognition towards the genre and the progress it represented.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter