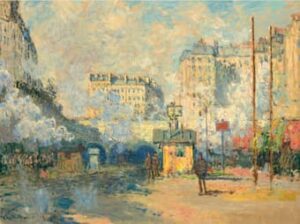

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Extérieur de la gare Saint-Lazare,

effet de soleil, painted in Paris, 1877. © Christie’s

The following article is the third and last of a three-part series on impressionism around the world; in France, in Europe and in our Modern World. In these articles, I explore the genre of impressionism. Born in France, it is known to have revolutionised the music world by breaking from over two centuries of traditions, rules and rigorous structures. While not presenting itself as better, it has provided many artists with an alternative and a new way of thoughts, free from boundaries and aiming towards exploration and development. As it grew from its native Paris to Europe and then the rest of the world, impressionism morphed into many different genres and explored new creative routes. Atonality would have never existed without it, nor would modernism or minimalism. Today, it is studied in music conservatoires — contradictory, that is where it was distancing itself from — and the works of Debussy are just as important as the ones of Bach.

George Gershwin in his New York apartment

with his first oil painting. © Wikipedia

A little less than two centuries after it was created and somehow codified, impressionism is everywhere; at times in a very obvious manner, but more than often disguised and hidden behind modernity. It is well present though, and undoubtedly anchored in the majority of the DNA of our modern musical works. Just like innovation becomes tradition, the revolutionary principles of impressionism soon integrated into teachings, schools and academies, and in no time composers started applying the ideas of Satie, Debussy and Ravel.

A composer which is immediately responsible for the rapid spread of the ideas of impressionism is of course the American composer Gershwin. Just like Ravel, he took a lot of his inspiration from afro-american music. What he had hoped would have sounded like jazz actually sounded more classical and impressionistic than anything else — his first concerto for piano is a great example of it. Gershwin’s music is hugely influential, particularly in the jazz world — he is responsible for the composition of many of the standards — and with him and his followers — including the pianist and composer Bill Evans — the audacity of impressionism was transmitted to the new generations.

Bill Evans: My Foolish Heart

Nadia Boulanger ©blog.edmodo.com

Another composer, who is mostly known for having been a teacher to Carter, Copland, Glass, Legrand, Milhaud and Schifrin, Boulanger also played her part in the diffusion of impressionistic ideas. A lot of her music was of course influenced by the works of Debussy and Ravel and as her teaching spread in Europe and North America, so did impressionism.

Messiaen notating birdsongs in the nature © Intertwining Arts

If atonality’s musical revolution has failed to impact as importantly as impressionism, it has nevertheless based some of its principles similarly. It reflects in some of Messiaen’s music for instance — if anything, his birdsongs are a testimony of a strong need for a connection with nature. His influence has reached the music of the Far East, and in Japan it can be heard in Takemitsu’s works and more recently the hugely successful (film) composer Sakamoto — he himself claims Debussy as a major influence. The circle is closed.

Back in the Western Europe culture, with the Soviet-born Australian Elena Kats-Chernin, whose Unsent Love Letters is a direct homage to Satie’s music.

Of course film music owes a lot to impressionism too; this extends to the works of Desplat, Newman, Shore, Howard, Elfman and the atmospheric work of Brian Eno.

Elena Kats-Chernin’s Unsent Love Letters is a direct homage to Satie’s music © Deutsche Grammophon

The British musician and composer is responsible for the birth of ambient music – and direct heir of Satie’s Furniture Music. With Eno’s Ambient 1/Music for Airports, the music’s function shifted from main actor to setting and scenery. Rather than thinking of it as background music, Eno’s ambient works created a new set of responsibilities for the music; to be part of the context, to create the atmosphere. One would choose the colour of a room, its furniture, its decoration, its smell and its music. A breakthrough that was perfect for our modern world, and allowed to cover many undesirable noises, and create synthetic ambiences. However, as brilliant as the idea was, it slowly morphed into new age music, and genre which in the author’s opinion is akin to a soup — a broth — of styleless-impressionistic-oriental-contentless-music. It is nevertheless a genre that inherited from the foundations of impressionism.

Brian Eno/Rhett Davies/Robert Wyatt: Music for Airports, “Ambient 1”: 1/1 (Bang on a Can)

The ideas of freedom and exploration, as well as depiction of sensations are today more than omnipresent, and if some of these originate as far as the 18th century, they have been restated and developed through the music of Satie, Debussy, Ravel and the impressionists. Many of us fail to recognise this influence as it is installed so deeply in our cultures, that just as with the music of Bach, Beethoven or Brahms it is often taken for granted. A revolution that has been done peacefully and perhaps more discreetly than expressionism or avant-garde, but which has nevertheless succeeded. There is something with the French and their revolutions…

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter