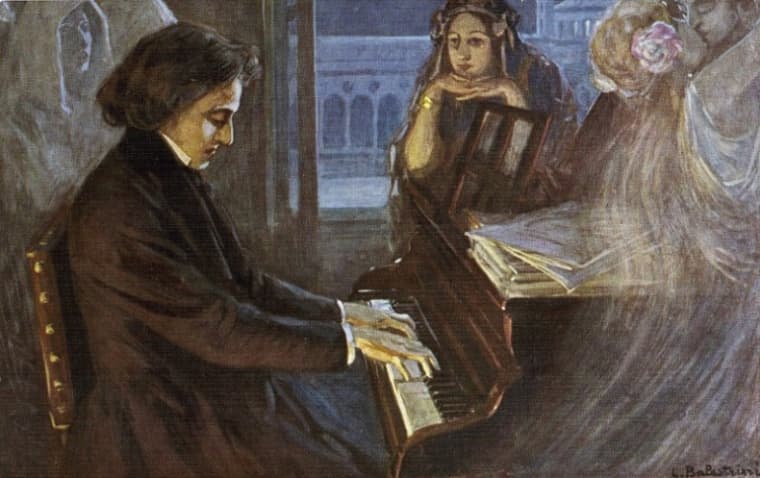

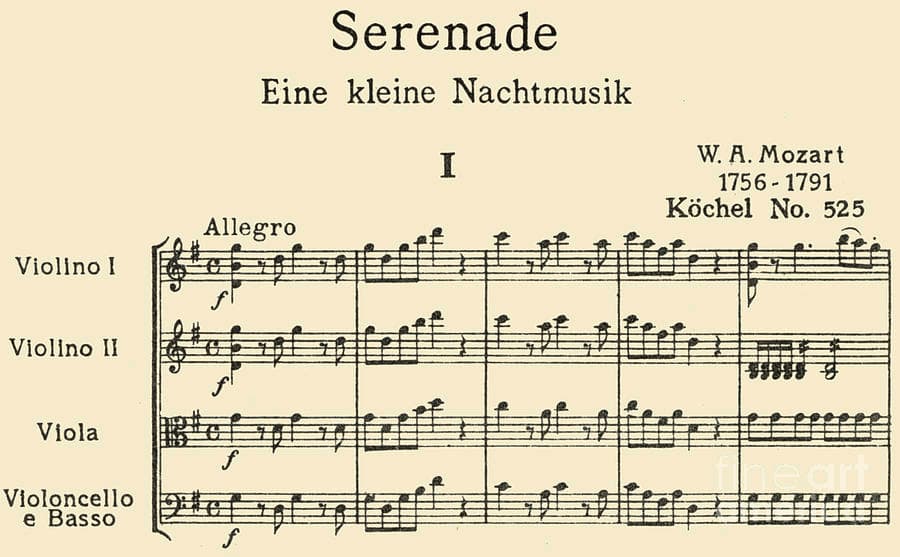

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Serenade No. 13 in G major, K. 524 “Eine kleine Nachtmusik”

The opening five bars of Eine Kleine Nachtmusik

In the wonderful and whacky world of musical nicknames, there is nothing more famous than “Eine kleine Nachtmusik” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. This “Little Night Music” or possibly better translated as “Little Serenade,” is widely considered “the most popular of all Mozart’s works.” Nobody really knows why and for what occasion it was written, but it was completed in Vienna in 1787, around the time Mozart was working on his opera Don Giovanni. “Serenades” were usually written as background music for social gatherings. They weren’t meant to have a long dramatic musical narrative or feature deep emotional contrasts. On the contrary, they were composed for the enjoyment of listeners and players, and “provide uncomplicated and unadulterated listening pleasure.” Normally, they were written on commission for lavish social gatherings, but in the case of the “Kleine Nachtmusik,” that information has been lost. After Mozart’s death, his widow Constanze sold a whole bundle of her husband’s compositions to the Offenbach publisher Johann André, including this Serenade. Johann André took his time, and the work was not published until about 1827, over 30 years after Mozart’s death. The nickname sort of comes from Mozart himself. Mozart had started to compile a catalog of his compositions, and made an entry titled “Eine kleine Nacht-Musik.” It doesn’t seem to have been intended as a special title, but Mozart “almost certainly merely indicated for his records that he had completed a little serenade.” One way or another, the nickname stuck.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 26 in D Major, K. 537, “Coronation”

Frankfurt am Main 1.5 Ducat 1790 Silver Strike Coronation Coin Leopold II. EF.

Sometimes, nicknames have a very complicated backstory. And that’s certainly the case with Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 26 in D major, K. 537, commonly known as the “Coronation Concerto.” The story starts with the coronation of Leopold II as Holy Roman Emperor in Frankfurt in 1790. It turned out to be a big party, with an ox-roast held in the main square and the meat distributed among the people. The main fountain was made to flow with wine, and on “temporary stages in the marketplaces all matters of performances were given in homage to the new Emperor.” And Antonio Salieri conducted the celebratory coronation mass in the cathedral. The most famous Viennese artists and musicians all attended with the exception of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who had not been invited. Since Frankfurt was filled with the Empire’s elite, musicians competed against each other in hopes of attracting audiences and commissions. Mozart took a gamble, pawned his silver and went into debt to travel to Frankfurt at his own expense. Mozart organized a concert on 15 October 1790 that was “poorly advertised and unfortunately timed,” and his gamble failed miserably. At that particular concert, Mozart performed two pianos concertos, the Piano Concerto No. 19, K. 459 and the Piano Concerto No. 26, K. 537. Both works had not been written for the occasion, but date from a couple of years earlier. The nickname “Coronation” is not by Mozart, and we actually seem to be dealing with not one but two “Coronation Concertos.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphony in D major, KV 297 “Paris”

The Tuileries Palace in 1865, where the Concert Spirituel took place

As we have seen with Joseph Haydn, a number of Mozart symphonies are nicknamed after geographic locations. Such is the case with the Symphony in D major, KV 297 nicknamed “Paris.” Mozart returned to Paris with his mother in the spring of 1778 to appear at the public concert series “Concert Spirituel.” As did happen with Mozart on a number of occasions, he was immediately confronted by some problems. Mozart claimed that the composer Giuseppe Cambini had sabotaged a performance of his Sinfonia Concertante, and to appease Mozart, the director of the concert series asked Mozart to write a new symphony. Mozart wasn’t particularly keen on French audiences, and he wrote to his father. “I don’t know if people will like it, I do not know… I can vouch for the few intelligent French people who may be there; as for the stupid ones, I see no great harm if they don’t like it. But I hope that even these idiots will find something in it to like…” As it happened, reviewers wrote, “Mozart had written a work that interests the mind without touching the heart.” I really don’t know about that. All you have to do is listen to the gorgeous clarinet lines, as Mozart used this instrument in this symphony for the first time ever.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: String Quartet No. 19 in C major, K. 465 “Dissonance” (Adagio-Allegro)

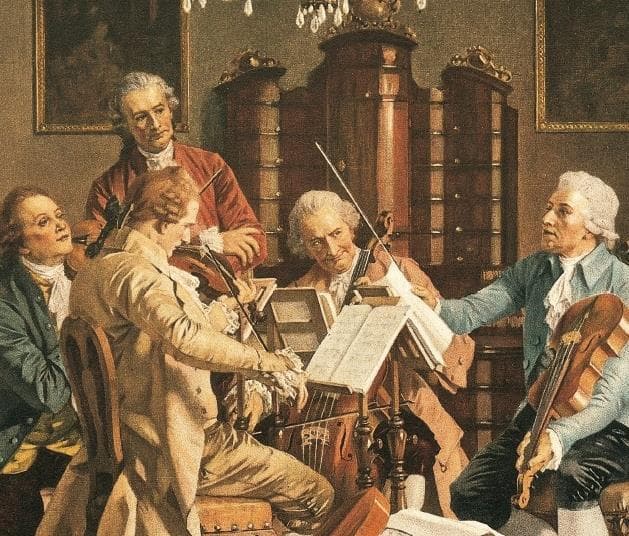

String quartet in the 18th century

I would have loved to be a fly on the wall when Haydn and Mozart met in person. Maybe they personally met as early as 1783, and it has even been suggested that they played chamber music together. Haydn had published a set of six string quartets Opus 33 in 1781, and profoundly inspired, Mozart decided to write six string quartets of his own. The six “Haydn” quartets were composed between 1782 and 1785, and a musicologist writes, “Mozart did not allow himself to be overcome. This time he learned as a master from a master; he did not imitate, he yielded nothing of his own personality.” Mozart did follow Haydn’s example of considering the string quartet as an intimate conversation shared by all instruments. Haydn was deeply impressed when he first heard these string quartets, and he famously told Leopold Mozart “before God and as an honest man I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name.” Three of the “Haydn” quartets have nicknames, with the “Dissonance” probably the most famous. That nickname, not by Mozart, was derived from the slow introduction to the opening movement. A highly chromatic, hence very dissonant progression of chords emerges over a pedal point by the cello. And while it does sound harsh to the ears, Mozart did not break any rules of harmony or composition.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Missa brevis in C major, K. 220 “Spatzenmesse”

Hieronymus von Colloredo (1732-1812), Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg

Hieronymus von Colloredo and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart did not get along at all. Archbishop Colloredo was Mozart’s employer in Salzburg, and he was seriously annoyed that Mozart was frequently absent from his post. I suppose, the archbishop had a point, as he learned when taking on the Salzburg post that during the last 10 years Mozart had been given leaves totaling six years and nine months. Mozart, in turn, claimed that the archbishop did not appreciate his talents, and that he didn’t pay him what he deserved. Mozart also complained that Colloredo treated him like a hired hand, with disdain and contempt. I suppose, dealing with a cocky teenager who had been a celebrated guest at the most illustrious courts in Europe, wasn’t really an easy task. However, Colloredo wasn’t particularly popular in Salzburg. He was a stern taskmaster who imposed the Enlightenment values of austerity and simplicity on a reluctant Salzburg population. One of his most unpopular decisions was to impose limitations on the length of church music. Mozart, for one, was outraged, and according to a cute anecdote, he got his revenge in his “Missa brevis” K. 220. That mass carries the nickname “Spatzenmesse,” (Sparrow Mass) and derives from recurring violin figures in the Sanctus and Benedictus. These musical figures resemble bird chirping, miming Colloredo’s constant “chirping” at Mozart to shorten the length of his Masses. The nickname, by the way, is not by Mozart.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Clarinet Trio, K. 498 “Kegelstatt”

Antique painted wooden skittles bowling pins with balls and box

I’ve always loved Mozart’s Clarinet trio in E-flat Major, K. 498. Scored for clarinet, viola, and piano, it carries the unusual nickname “Kegelstatt.” Since my German isn’t very good, I had to look up the word in the dictionary. It turns out that “Kegelstatt” is a specific Viennese term for the outdoor alley where the game of skittles—an old European variety of bowling—is played, typically in a garden setting. What then is the connection between the Mozart Clarinet Trio and an old bowling alley? Luckily we know that the work is dedicated to Franziska von Jacquin. Franziska was Mozart’s student, and daughter of Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin. Jacquin was a noted scientist who was Professor of Botany and Chemistry at the University of Vienna. The extended Jacquin family held weekly gatherings, and Mozart was a frequent visitor. According to contemporary witnesses, they engaged in discussions, games, and music-making. The first performance of the Trio took place at one of these afternoon house concerts, with Franziska playing the piano, Mozart the viola, and Anton Stadler the clarinet. The nickname “Kegelstatt” seems to possibly indicate that the piece was “composed during an afternoon game of skittles.” Once again, the nickname is not by Mozart.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major, K. 291 “Turkish” (Tempo di menuetto)

Battle of Vienna, 11 September 1683

In 1529 and 1683, Turkish troops famously laid siege to the city of Vienna. According to legend, the invention of the Croissant—imitating the distinct crescent symbol of the Ottoman Empire—and the establishment of the first Viennese coffeehouse were the direct culinary outcome of these adversarial encounters. I am not convinced that this story is actually true, but Vienna was fascinated with various aspects of Turkish culture. Turkish art found its way into local architecture, sculpture, and music. And special uniformed infantry band units known as Janissaries endlessly fascinated composers. There are plenty of “Turkish Marches” in works by Haydn, Beethoven, and Mozart. Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5, composed in 1775 carries the nickname “Turkish” because it makes use of stylized Turkish musical elements in the concluding movement. The soloist dominates this graceful and melodious Rondo, and the forceful central section makes all kinds of references to Janissary music. We can hear a bass drum, the triangle, cymbals, and the piccolo flute, but also a characteristic march rhythm. Mozart, of course, had nothing to do with the nickname at all.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major, K. 291 “Turkish” – III. Tempo di menuetto (Jascha Heifetz, violin)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Divertimento in F Major, K. 522 “Ein musikalischer Spaß” (Some musical Fun)

The Enraged Musician by English artist William Hogarth

One of my favorite scenes in the movie Amadeus takes place in a salon in the early hours of the morning. Everybody had plenty to drink, and Mozart is asked to perform some musical party tricks by improvising in the musical styles of contemporary composers. His big rival Antonio Salieri is in the audience in disguise, and he challenges Mozart to improvise in the style of Salieri. Immediately, Mozart launches into a clumsy parody full of repetitive and nonsensical musical figures. The scene ends with the audience rolling with laughter and the famous Mozart giggles. Poor Salieri is humiliated and seething with rage. Being a movie, the scene is entirely fictional, but Mozart did have a wicked sense of humour and on occasion, he did make anonymous fun of his colleagues. In his personal catalogue of works, Mozart writes “14th June 1787. Ein Musikalischer Spass; consisting of an Allegro, Minuet and Trio, Adagio and Finale.” As such, the nickname of the Divertimento in F major, K. 522 was actually supplied by Mozart. However, we still don’t know why, and for what occasion he composed the piece. It seems to be fairly certain, however, that Mozart was poking fun at incompetent compositions and dilettante performances. “It is sprinkled with clumsy repetitive figures, together with passages designed to mimic the effects of inaccurate notation and poor performance. Comedic devices include the use of asymmetrical phrasing, the use of secondary dominants where subdominants are required, discord in horns, whole tone scales, and even early polytonality.” Full of intentional mistakes Mozart does take a swipe at his dilettante colleagues of his time, “whose lack of imagination and artless compositional technique is here mercilessly demonstrated.” If it’s any consolation, I don’t think he actually meant to parody Salieri. Two additional nicknames, the “Village Musician’s Sextet,” and the “Farmer’s Symphony” were added after Mozart’s death.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphony No. 41 in C Major, K. 551 “Jupiter”

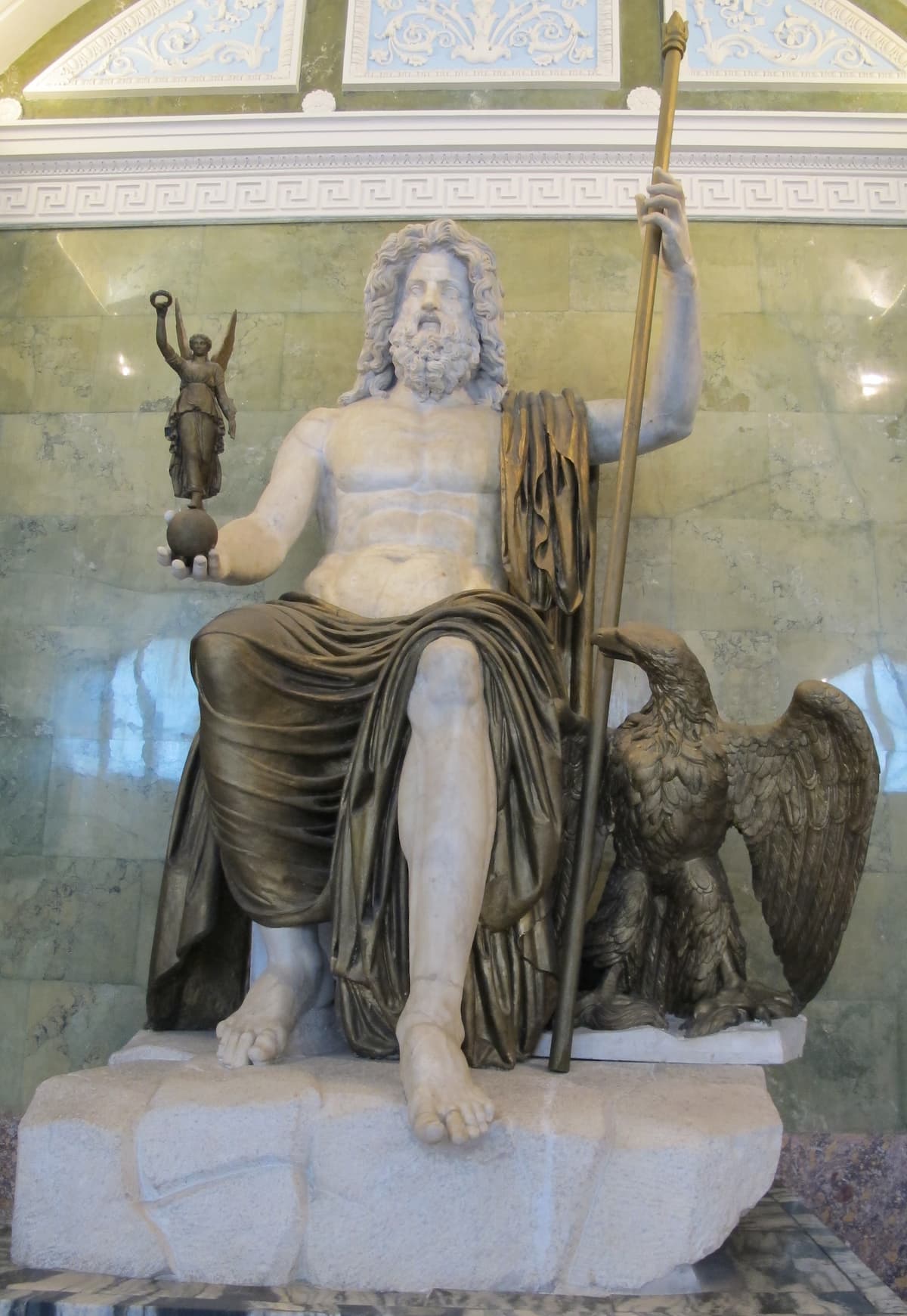

Statue of Jupiter

Mozart’s last and most famous symphony was completed on 10 August 1788. Known around the world as the “Jupiter” Symphony, Mozart did not append this particular nickname. According to his son Franz Xaver Mozart, it was the London impresario Johann Peter Salomon who devised this nickname as a catchy advertising device for the symphony’s London performances in 1819. An alternate story credits the English music publisher Johann Baptist Cramer. An uncorroborated anecdote reports that the first chords “reminded Cramer of the god Jupiter and his thunderbolts.” It is entirely possible that the flourishes of the trumpets and drums in the first movement, “evoked gestures of nobility and godliness in the minds of the audiences at that time.” The “Jupiter” nickname became permanent in 1823 when it was included on the title page of the first printed edition of a version for solo piano. We have no idea what Mozart might have thought of this particular nickname, with a Mozart scholar writing, “The title ‘Jupiter’ takes rank with the titles ‘Emperor Concerto’ and ‘Moonlight Sonata’ as among the silliest injuries ever inflicted on great works of art… “Mozart’s musical culture may have been Italian, but his artistic nature was neither Roman nor Greco-Roman. He was as Greek as Keats.” By that reasoning, the Symphony No. 41 might reasonably carry the nickname “Zeus,” the god of the sky in ancient Greek mythology.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter