Joseph Haydn

Over the last couple of days, I have conducted a little musical experiment. I noticed that 35 out of 106 Symphonies by Joseph Haydn carry a nickname of sorts. There is a “Bear,” a “Queen,” a “Philosopher,” a “Surprise,” a “Miracle” and so on. My question was relatively simple. Without looking at a score or reading various descriptions, would I be able to hear the nickname in the music? I wasn’t particularly worried whether that nickname originated with Haydn or with somebody else. I suppose publishers might add descriptive titles to characteristic works in order to make their products more attractive to buyers. Alternately, contemporary critics, concert presenters, or even audience members also added nicknames. In the absence of a consistent numbering system, it was much easier for the concert-going public to identify a symphony by its nickname. While some nicknames seemingly lend themselves to be heard in the music, others are far more abstract. Let’s get started with one of Haydn’s most famous nickname symphonies.

“Surprise”

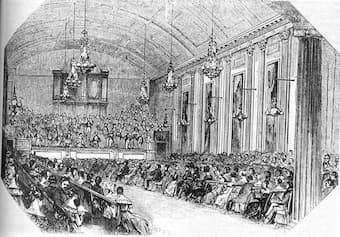

Hanover Square Rooms

The Symphony No. 94 is so famous that the “Surprise” really isn’t a surprise anymore. Composed during Haydn’s first visit to England, Haydn conducted the premiere at the Hanover Square Rooms in London in March 1792. I’ve long heard the anecdote that Haydn had wanted to startle an inattentive and sleeping audience into paying attention. The “Surprise” happens in the second movement when the orchestra joins the first violins in a sudden fortissimos chord. It is like an exclamation mark at the end of an otherwise very quiet opening. The music immediately returns to the quiet beginning and in the variations that follow, the surprise is not repeated. The Haydn biographer Georg August Griesinger asked the composer whether he composed the surprise to wake up the audience. Haydn replied, “No, but I was interested in surprising the public with something new, and in making a brilliant debut, so that my student Pleyel, who was at that time engaged by an orchestra in London and whose concerts had opened a week before mine, should not outdo me. The first Allegro of my symphony had already met with countless Bravos, but the enthusiasm reached its highest peak at the Andante with the Drum Stroke. Encore! Encore! sounded in every throat…” As a listener, there is no escaping that delicious fortissimo chord, and it still makes a huge impression.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 94 in G Major “Surprise” (Andante)

“Oxford”

University of Oxford

A number of Haydn symphonies carry nicknames that identify a particular geographic location or place. When I listened to the “Oxford” I half expected to find some musical references to this city dominated by the 38 colleges of its prestigious university. Truth be told, I couldn’t hear anything of that sort, and the nickname “Oxford” has its origin not necessarily in the world of music. In his day, Joseph Haydn was the most famous composer in Europe. He had been composing in seclusion for the Esterházy family for many decades, but when Johann Peter Salomon brought Haydn to England at the beginning of 1791, Charles Burney suggested that Haydn should receive an honorary doctorate degree from Oxford University. Since this degree required the candidate to prove his skill in composition, Haydn presented a number of compositions for examination, and he conducted three concerts at the University. Haydn later told a friend, “I felt very silly in my gown, and I had to drag it around the streets for three whole days. But I have much to thank for this doctor’s degree in England; indeed, I might say everything; as a result of it, I gained acquaintance of the first men in the land and had entrance into the greatest houses.” As such, it’s actually not surprising that Haydn’s Symphony No. 92 would eventually receive the nickname “Oxford.” I guess nobody actually knew that the origins of the work go back to Paris, and a commission by the French aristocrat, the Comte d’Ogny.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony Nr. 92 in G major “Oxford”

“London”

The 12 Symphonies that Haydn wrote for his two journeys to England are commonly known as the “London Symphonies.” The last of these 12 symphonies, the Symphony No. 104, however, also carries the nickname “London”. This seems a bit confusing, but the symphony nickname apparently is derived from the last movement of the work. We hear a soft drone in the horns and cellos before the violins introduce a folksy melody. This melody returns throughout the movement, and to audiences at the first performance in 1795 it sounded “like a street vendor’s cry frequently heard in the markets of London.” Some experts think that it might have been either “Live cod” or “Hot cross buns.” Audiences thought that Haydn had musically paid homage to their city and they began calling the work “London” Symphony. Funny thing, the melody has actually nothing to do with London. It turns out that the folksy melody is actually based on a Croatian folk song. Haydn never visited Croatia, but he lived and worked in an Austro-Hungarian border region that featured a substantial number of Croatian ethnic enclaves. The folksy theme of the No. 104 Finale is actually based on “Oj, Jelena, Jelena, jabuka zelena,” translated as “Oh, Helen, Helen, green apple of mine.” Instead of calling it the “London” Symphony, we should probably call it the “Green Apple” Symphony.

The 12 Symphonies that Haydn wrote for his two journeys to England are commonly known as the “London Symphonies.” The last of these 12 symphonies, the Symphony No. 104, however, also carries the nickname “London”. This seems a bit confusing, but the symphony nickname apparently is derived from the last movement of the work. We hear a soft drone in the horns and cellos before the violins introduce a folksy melody. This melody returns throughout the movement, and to audiences at the first performance in 1795 it sounded “like a street vendor’s cry frequently heard in the markets of London.” Some experts think that it might have been either “Live cod” or “Hot cross buns.” Audiences thought that Haydn had musically paid homage to their city and they began calling the work “London” Symphony. Funny thing, the melody has actually nothing to do with London. It turns out that the folksy melody is actually based on a Croatian folk song. Haydn never visited Croatia, but he lived and worked in an Austro-Hungarian border region that featured a substantial number of Croatian ethnic enclaves. The folksy theme of the No. 104 Finale is actually based on “Oj, Jelena, Jelena, jabuka zelena,” translated as “Oh, Helen, Helen, green apple of mine.” Instead of calling it the “London” Symphony, we should probably call it the “Green Apple” Symphony.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 104 in D Major “London” (Finale)

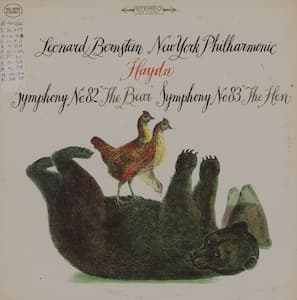

“Bear”

Let’s turn to two symphonies that are nicknamed after animals, the Symphony No. 82 in C major nicknamed the “Bear,” and the Symphony No. 83 in G minor nicknamed the “Hen.” Haydn was in great demand as a symphony composer, and the Count d’Ogny commissioned a set of six symphonies from Haydn for the concerts organized by the “Olympique” Lodge of the Paris freemasons. These six symphonies are commonly known as the “Paris” symphonies, even though Haydn never visited the French capital. In musical terms, he had a larger orchestra at his disposal than ever before, including reinforced woodwinds and a large string section. And Haydn took full advantage of this situation. The “Bear” Symphony was first performed in 1787 under the direction of the “Black Mozart,” Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. The “Bear” nickname comes from the final movement when a low sustained drone is accentuated by a grace note on the downbeat. This opening lends a carnival-like atmosphere to the movement and to audiences it suggested music used to accompany dancing bears. I suppose dancing bears must have been a popular form of street entertainment in Paris. And with a bit of imagination, the lumbering bear is doing all sorts of tricks that can be nicely heard in the development section.

Let’s turn to two symphonies that are nicknamed after animals, the Symphony No. 82 in C major nicknamed the “Bear,” and the Symphony No. 83 in G minor nicknamed the “Hen.” Haydn was in great demand as a symphony composer, and the Count d’Ogny commissioned a set of six symphonies from Haydn for the concerts organized by the “Olympique” Lodge of the Paris freemasons. These six symphonies are commonly known as the “Paris” symphonies, even though Haydn never visited the French capital. In musical terms, he had a larger orchestra at his disposal than ever before, including reinforced woodwinds and a large string section. And Haydn took full advantage of this situation. The “Bear” Symphony was first performed in 1787 under the direction of the “Black Mozart,” Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. The “Bear” nickname comes from the final movement when a low sustained drone is accentuated by a grace note on the downbeat. This opening lends a carnival-like atmosphere to the movement and to audiences it suggested music used to accompany dancing bears. I suppose dancing bears must have been a popular form of street entertainment in Paris. And with a bit of imagination, the lumbering bear is doing all sorts of tricks that can be nicely heard in the development section.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 82 in C Major, “The Bear” (Vivace)

“Hen”

The companion symphony to the “Bear,” is the Symphony No. 83 nicknamed the “Hen.” Haydn originally intended this symphony as the third piece in the cycle of Paris Symphonies. Haydn did have a wicked sense of humour, and he certainly knew that he was composing for a musically sophisticated crowd in Paris. The opening movement begins in a highly dramatic fashion and in the minor key. There seems to be much passion with ascending minor passages and dramatic silences. Without preparation, Haydn launches a thematic contrast taken straight from the opera buffa. This theme, which gives the Symphony its “Hen” nickname, evokes a very funny clucking sound. At the same time the accompanying pattern in the oboe might represent a hen scratching. Since that nickname only originated in the 19th century, it is difficult to know if the “Hen” was actually heard by contemporary audiences. The juxtaposition of the serious opening with the ironic chicken theme, however, is pure genius.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 83 in G minor “The Hen” (Allegro spiritoso) (Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Neville Marriner, cond.)

“Miracle”

Chandeliers in Hanover Square Rooms

When I saw the nickname “Miracle” attached to Haydn’s Symphony No. 96, I was originally thinking that it might have some religious significance. But when I actually listened to this piece, I could not hear anything remotely religious. As it turns out, the nickname actually refers to something that happened in King’s Theatre on 2 February 1795. The hall was filled to capacity, and everybody was waiting for the performance of a new symphony by Joseph Haydn. It was reported that Haydn directed the orchestra from the keyboard, and curious members of the audience rushed toward the stage in order to get a closer glimpse of the famous Haydn. As an early Haydn biographer reports, “The seats in the middle of the floor were thus empty, and hardly were they empty when the great chandelier crashed down and broke into bits, throwing the numerous gathering into great consternation. As soon as the first moment of fright was over and those who had pressed forward could think of the danger they had luckily escaped and find words to express it, several persons uttered the state of their feelings with loud cries of “Miracle! Miracle!” However, the “Miracle” story has a delicious twist. We actually know that the chandelier fell in the last movement of Symphony No. 102, as the Morning Chronicle wrote the following day. “The last movement was encored: and notwithstanding an interruption by the accidental fall of one of the chandeliers, it was performed with no less effect.” The “Miracle” did happen for sure but the nickname was actually assigned to the wrong symphony.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 96 in D major, “Miracle”

“Morning”

John Hoppner: Portrait of Franz Joseph Haydn

While the “Miracle” can’t actually be heard in the music, the “Morning” in Symphony No. 6 is readily apparent. Haydn spent nearly 30 years in service to the princes Esterházy. He later wrote to his biographer, “my employer was satisfied with everything I produced; I received applause and praise; as the Director of the orchestra I was allowed to experiment and observe…i.e. I had the chance to improve, to make additions and cuts, to take risks. I was isolated from the world; there was no one nearby to confuse or irritate me, and so I had no choice but to be original.” Paul Anton Esterházy was a music lover, and his favorite composition was the “Four Seasons” by Vivaldi. He told Haydn to compose a similar series of pieces depicting the times of day. Since the Prince had been enlarging the orchestra by adding woodwinds, horns and doubling up on strings, Haydn decided to demonstrate the power of this larger orchestra to the Prince. Haydn composed three Symphonies, nicknamed “Morning,” “Noon,” and “Night” Unlike nearly all of Haydn’s symphonic nicknames the moniker “Le matin” appears to have originated with the composer. The nickname derives from the slow introduction of the opening movement, clearly depicting a sunrise. The first violins enter alone, then the second violins join in harmony and soon the entire orchestra rises to a bright climax as the sunrise is breaking the horizon.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 6 in D Major “Le matin” – I. Adagio – Allegro (St. Luke’s Chamber Ensemble; Krista Bennion Feeney, cond.)

“La Reine”

Marie Antoinette

The nickname “La Reine” (The Queen) might actually refer to a number of regal monarchs. However, when we learn that it was written for Paris the queen in question was no other than Marie Antoinette. The commission for the six “Paris Symphonies” carried a substantial financial stipend. For each symphony, Haydn received the equivalent of 225 gulden, making a total of 1350 gulden in all for the six works. That was more money than Haydn made in an entire year working for Nicholas Esterházy. Working for the prince carried an annual salary of about 800 gulden, which enabled him to live in circumstances approaching the upper-middle class. It paid for a nice home, servants, a carriage with liveried footmen, good clothing, a comfortable lifestyle, and the ability to save some money. Always the businessman, Haydn jumped at the Paris opportunity. As a composer, Haydn also relished the challenge of writing music for an orchestra of 67 players, and for an audience made up of the highest levels of the French aristocracy and plutocracy. Scholars have suggested that the “Paris Symphonies” represent Haydn’s finest writing in the symphonic genre up to this point.” And in terms of paying homage to the French aristocracy, he knew exactly what to do. The second movement is one of Haydn’s famed double-variation forms based on a French folk tune, with the finale sounding one more local tune. The nickname “La Reine” does not refer to the use of French tunes, but was attached because it supposedly was Marie Antoinette’s favourite symphony.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 85 in B flat Major, “La Reine”

“Maria Theresia”

Maria Theresia

The nickname “Maria Theresia” makes reference to the Habsburg Holy Roman Empress and mother to Maria Antonia, later to become Marie Antoinette. In 1773, Maria Theresia visited the Eszterháza family estate. Prince Nicholas gave her a regal welcome, and built a small mansion for the Empress where the garden entertainment took place. A cute anecdote relates that after an evening of lavish entertainment, Maria Theresa asked the prince how much this wonderful little mansion had cost. “Eighty thousand florins,” Prince Nicholas replied. “Oh!” exclaimed the Empress, “this is a mere bagatelle for an

Esterházy Prince!” To this day, the word “Bagatelle” stands proudly above the gate to the mansion, as this “has been the name of the luxurious building ever since.” Haydn served as Kapellmeister to Nicholas Eszterháza and it was assumed that his Symphony No. 48 was exclusively written for the visit by the empress, hence the nickname “Maria Theresia.” Although the symphony features plenty of regal brass fanfares, a manuscript of the work was subsequently found dated 1769, so it has nothing to do with the Empress at all. The nickname, however, in order to increase sales for the publisher, has survived until this day.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 48 in C Major, “Maria Theresa”

“Clock”

A clock at Esterhazy Palace

We are almost out of time, and Haydn’s “Clock” Symphony seems a perfect composition to finish this article. It was the ninth of his twelve “London” symphonies, and premiering on 3 March 1794. The audience was enthusiastic, and the press highly complementary. A press report reads, “As usual the most delicious part of the entertainment was a new grand symphony by HAYDN; the inexhaustible, the wonderful, the sublime HAYDN! The first two movements were encored, and the character that pervaded the whole composition was a heartfelt joy. Every new symphony he writes, we fear, till it is heard, he can only repeat himself; and we are every time mistaken.” The second movement, from which the symphony gets its nickname, begins with plucked strings and bassoons. That ticking rhythm underlines the entire movement, and a more recent critic wrote, “Haydn has a gratifying number of different clocks in his shop, offering tick-tock in a happy variety of colors.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 101 in D major, “Clock” (Andante)

I truely enjoy reading and listening to the articles and music you send. Thank-you so very much.

Does number 98 have a name