Franz Schubert, 1825

During the first decades of the 19th Century, the city of Vienna must have been a real party town. Conductors, performers and composers from all parts of Europe flocked to the city to take advantage of the rapidly expanding employment and business opportunities. Immigrant composers such as Ludwig van Beethoven and Gioachino Rossini ferociously competed for local audiences in a highly competitive environment. Let’s not forget, however, that Vienna was home to a number of highly talented composers, foremost among them Franz Schubert. Schubert had a difficult time gaining a musical foothold, and during his lifetime, a relatively small circle of friends admired his music. Almost unbelievably, Schubert died at the age of 31 and on his large tombstone the poet Grillparzer wrote, “Here music has buried a treasure, but even fairer hopes.” Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a vast treasure trove of music, hundreds of lieder, symphonies, sacred music, operas, incidental music, and works for piano and chamber music. Robert Schumann called Schubert a “natural genius of music,” and this first story of nicknamed compositions by Franz Schubert directly involves Robert Schumann.

Symphony No. 9 in C Major, D 944 “Great C Major”

Schubert: Great C Major

In October 1838, Robert Schumann first traveled to Vienna. Just a couple of months earlier, his fiancée Clara Wieck had performed for Viennese audiences to great acclaim, and Schumann was desperately trying to find a Viennese publishing house for his musical journal, the “Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.” Schumann had made good contacts with Metternich and the police chief Sedlnitzky, but his publishing plans were jealously opposed by the local music publisher Haslinger. From a professional point of view, the trip was a failure, but Schumann personally met Johann Vesque von Püttlingen, Mozart’s son Franz Xaver Wolfgang and his girlfriend Julie von Webenau. Schumann also decided to visit Ferdinand Schubert, Franz Schubert’s brother. He writes, “Ferdinand knew of me because of that veneration for his brother which I have so often publicly expressed; told me and showed me many things. … Finally, he allowed me to see those treasured compositions of Schubert’s, which he still possesses. The sight of this hoard of riches thrilled me with joy; where to begin, where to end! Among other things, he drew my attention to the scores of several symphonies, many of which have never as yet been heard, but were shelved as too heavy and turgid.” Among these unknown treasures was the manuscript of a symphony in C Major dated March 1828. Upon his return to Leipzig, Schumann immediately arranged for the premiere performance of this new Schubert Symphony at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1839, with Felix Mendelssohn conducting. This symphony received the nickname “Great C.” It is a magnificent symphony for sure, but the title was simply attached to distinguish it from the other Schubert symphony in the key of C Major D. 589, which is appropriately nicknamed the “Little C.”

String Quartet in A minor, No. 13, D. 804 “Rosamunde”

Helmina von Chézy

In 1823, Franz Schubert was asked to compose incidental music to a play by the German dramatist and playwright Helmina von Chézy. Chézy, who had previously written the libretto for Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Euryanthe, presented Schubert with her new play Rosamunde, Fürstin von Zypern (Rosamunde, Princess of Cyprus). The play centers on the attempt of Rosamunde, who was raised anonymously as a shepherdess by the widow Axa, to reclaim her throne. The governor Fulvio, who had already murdered Rosamunde’s parents, tries everything to stay in power. Initially, he spins a sordid tale of intrigue, and when that fails, proposes marriage. Once he is turned down, he attempts to poison Rosamunde. However, her claim is backed by a deed in her father’s hand, and she enjoys the support of Cypriots and the Cretan Prince Alfonso, her intended husband. Fulvio’s attempts all fail, and he dies by his own poison while Rosamunde ascends the throne. Schubert’s music and Chézy’s play premiered in Vienna on 20 December 1823. As far as we can tell, the play was a resounding failure. Schubert’s music, which consisted of an overture originally associated with the melodrama Die Zauberharfe (The Magic Harp) and ten numbers, was soon forgotten as well. Notwithstanding, in 1824 Schubert reused one of his Rosamunde melodies in the second movement of his String Quartet in A minor, D. 804. This work, which has subsequently become known as the “Rosamunde Quartet” was dedicated to Ignaz Schuppanzigh, who famously premiered many of Beethoven’s late string quartets.

Piano Sonata in C Major, D840 “Reliquie”

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 15 in C Major, D. 840, “Reliquie” (excerpts) (Mitsuko Uchida, piano)

Grave of Schubert, Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery), Vienna

Franz Schubert started work on a piano sonata in C major in April of 1825. For one reason or another, Schubert left this composition incomplete. When it was first published in 1861 it carried the nickname “Reliquie,” because the publisher assumed that it was Schubert’s last piano sonata. Isn’t it interesting how these musical fragments were elevated to objects of religious significance? Relics in religion usually consist of the “physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangible memorial.” Since it was mistakenly assumed that Schubert had died before he could finish this sonata, the fragments represented precious relics from a musical genius and saint. Schubert did complete the “Moderato” first movement and the “Andante” second movement. The third movement “Minuetto” in A-flat Major comprises an incomplete “Minuetto” section that breaks off after about 80 measures, and a complete “Trio” in G-sharp minor. The concluding “Allegro” is scored in the tonic key, but the music breaks off at measure 271 in the key of A Major. Schubert, of course, did not die in April 1825, so what prompted him to stop working on the composition? Some experts thought that Schubert was frustrated with the score of the “Reliquie” and was unsure how to go about completing the work. Somehow, this seems rather unlikely. We know that Schubert was simultaneously working on a piano sonata in A minor, and he might simply have set the unfinished movements aside in order to continue to work on this new composition. In Schubert’s mind, presumably, the sonata was complete, but he never got around to writing it down. The nickname “Reliquie,” however, has stuck.

Rondo in D major, D 608 “Notre amitié est invariable”

Schubert: Rondo in D Major

In January 1818 Schubert sketched the Rondo in D major, D. 608, for piano duet. The work carries the motto “Notre amitié est invariable” (our friendship is unchangeable), either supplied by Anton Diabelli or by Schubert himself. The Schubert biographer Otto Deutsch explains “in the final section, from measure 232, the music is set so that the player’s hands cross in a manner of playing that possibly is meant to illustrate and underline the motto… it points to Schubert’s friendship with his favorite duet partner, the Hungarian-born pianist and civil servant Josef von Gahy.” Gahy was a very good amateur pianist, and a close personal friend. Together they frequently played compositions for piano four hands at the famous Schubertiade meetings. Gahy later told Schubert’s first biographer: ‘The hours I spent making music together with Schubert are among the richest enjoyments of my life and I cannot think of those days without being deeply moved… The clear fluent playing, the individual conception, the manner of performance, sometimes delicate and sometimes full of fire and energy, of my small plump partner afforded me great pleasure… it was just on these occasions that Schubert’s genial nature was displayed in its full radiance and he used to characterise the various compositions by humorous interpolations, which sometimes included ironic, though always pertinent, remarks.”

Wind Nonet in E-flat minor, D 79 “March for Franz Schubert’s Funeral”

Franz Schubert: Wind nonet in E-Flat Minor, D. 79 (Zefiro; Alfredo Bernardini, cond.)

The young Schubert, 1814

At the age of 16, Franz Schubert composed a Wind Nonet in E-flat minor for two clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon, two horns and two trombones. Curiously, Schubert subtitled the works “March for Franz Schubert’s Funeral.” As you might well imagine, there are various theories about the origin of this composition. One such theory explains that a few months earlier, in May 1812, Schubert had to cope with the death of his mother. “He reacted by throwing himself heart and soul into composition, neglecting his studies of Latin and Mathematics at the prestigious Imperial Seminary where he had been a boarder since 1808, and being severely rebuked by his tutors.” It might well be that writing his own funeral March was his “response to the college’s lack of compassion.” More sinister theories suggest that this Nonet already “shows the deepest declaration of a presentiment of his tragic life and early death.

Concerto in D Major for violin and orchestra, D 345 “Konzertstück”

Schubertianer (Schubertiade meetings) © Wien Museum / Leopold Kupelwieser, Gesellschaftsspiel der Schubertianer in Atzenbrugg, 1821

Schubert was a capable violinist and violist, who first played in the school orchestra. He continued to play the viola at Schubertiade meetings and in semi-public concerts held by the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. Schubert was also an accomplished pianist, and his brother Ferdinand reports that he “played without virtuosic flare but with full insight and expressivity.” I suppose Schubert did not have the flamboyant and public persona to feel comfortable on the concerto stage. Maybe that is the reason why Schubert never wrote a dedicated concerto. Sadly, there are no concertos for the piano or for wind instruments, only three short concertante works for violin and orchestra. A scholar writes, “Schubert made but few concessions to the virtuoso concept, preferring to imbue his works with a sense of absolute certainty and serenity rather than turn them into showcases for displays of technique.” At the age of 17, Schubert became an assistant teacher at the school of his father, teaching the youngest children. In his spare time, he gave private music lessons, and between 1815 and 1816 he composed 250 songs and 132 other works. Among them is the “Konzertstück” (Concert Piece) in D for violin and orchestra. Maybe Schubert was attempting to compose a violin concerto, or he might have written the work for a community orchestra. In the event, we have no idea if it was ever performed. The “Konzertstück,” as it was called, was only published in 1897.

Trout Quintet, D. 667

Schubert: Die Forelle (The Trout)

One of Schubert’s most famous and best-loved compositions is nicknamed after a fish. Well, that’s at least partially true, as it was nicknamed after a song that featured a fish. Schubert’s song “Die Forelle” (Trout) was so popular that it was published a number of times during his lifetime. In fact, it was the favorite song of Sylvester Paumgartner, a mining engineer, amateur cellist, local patron of the arts and an occasional participant in Schubertiade gatherings. Paumgartner resided in the town of Steyr, located halfway between Vienna and Salzburg. During the summer of 1819, Schubert and his travel companion Johann Michael Vogl, a baritone at the Vienna court opera and a tireless promoter of Schubert’s works, visited Paumgartner’s home. Schubert had free use of the music room, and he staged a number of midday concerts in the salon. In addition, Paumgartner also requested that Schubert compose a work featuring his favorite “Trout” song. Paumgartner further demanded that the new work was to “adopt the structure and instrumentation of his favorite chamber work, the Hummel Quintet, featuring piano, violin, viola, cello, and double bass.” For his “Trout Quintet,” Schubert used the song for a theme and variations in the fourth of five movements. As a critic wrote, “ on other large work did Schubert produce so many carefree, and spirited tunes.”

String Quartet in D minor, D 810 “Death and the Maiden”

Franz Schubert: String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, D. 810, “Death and the Maiden” (Emerson String Quartet)

Egon Schiele: Death and the Maiden

As we have seen and heard in the “Trout Quintet,” Schubert transferred one of his earlier songs into an independent instrumental composition. He followed the same process with his song “Death and the Maiden,” composed in February 1817. The text comes from the German poet Matthias Claudius, and it unfolds as a conversation between a young girl and the grim reaper. As the girl pleads “Pass me by! And do not touch me,” death entices her to “give me your hand; softly shall you sleep in my arms!” Seven years later, in 1824, Schubert reuses the piano accompaniment from this song as the theme in the second movement of the “Death and the Maiden” string quartet. His motivation for this particular song transfer seems to have been highly personal. Schubert had contracted syphilis in 1822, and he soon exhibited serious symptoms. He was admitted to the Vienna General Hospital for six months, and endured numerous cold baths, extensive fasting and the administration of poisonous mercury. Despite, or because of these treatments, Schubert clearly sensed that his life was going to be cut short, and that he would be having a conversation with death very soon. This anguish, as many commentators have told us, is most acutely felt in the “Death and the Maiden” String Quartet.

Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D 759 “Unfinished”

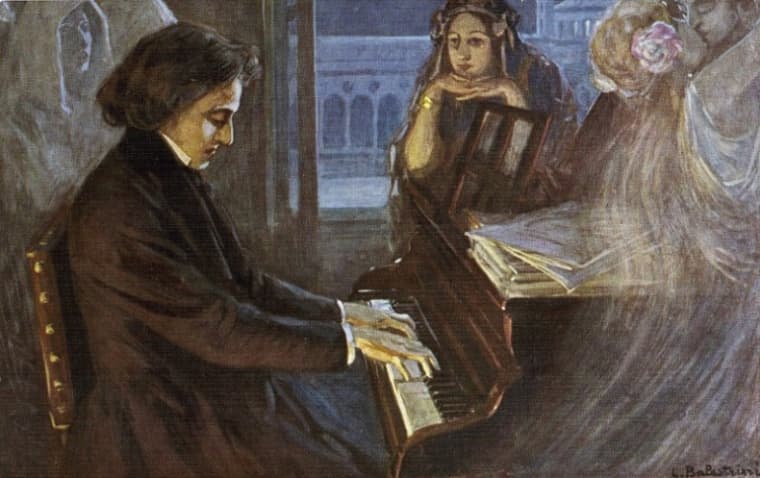

Klimt: Schubert at the Piano

Schubert’s B-minor Symphony No. 8 carries the nickname “Unfinished,” precisely because it’s unfinished. One of the most exciting mysteries in classical music is actually the question why Schubert never completed the work. The composer received an honorary diploma from the Music Society in Graz in 1823. To thank the Society, he sent his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner, a leading member of that organization, an orchestral score he had written in 1822. It consisted of two complete symphonic movements and the first two pages of the start of a Scherzo. The rest of the Scherzo was discovered after Schubert’s death, but the finale movement has never been found. One theory suggests that Schubert recycled the final movement in his incidental music for Rosamunde, but not everybody agrees. Other theories suggest that Schubert stopped work in the middle of the Scherzo because he associated it with his initial outbreak of syphilis. For his part, Hüttenbrenner initially hid the manuscript and only showed it to the conductor Johann von Herbeck 40 years later. As such, the two completed movements were premiered on 17 December 1865 in Vienna. On the 100th anniversary of Schubert’s death in 1928, a worldwide competition was held to complete the “Unfinished,” but the real reason why Schubert stopped working on this symphony remains hidden.

Trio in E-flat Major, D 897 “Notturno”

I want to conclude this little survey of nicknamed compositions by Franz Schubert with the Adagio for Piano Trio D 897. Composed in 1827 it was first published many decades later, and since the opening section provides a feeling of nighttime serenity, it is aptly nicknamed “Notturno” by the publisher. It is a piece of heavenly beauty, with its hypnotic melody supported by harp-like arpeggios on the piano.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

This is a wonderful article and quite comprehensive in its extent. I would like to add the nickname “The Gasteiner sonata”, (D850) named so because it was a very enjoyful time that Schubert experienced in Gastein.

There are some more names existent, but not all the pieces are commonly known.

Thank you for the article!