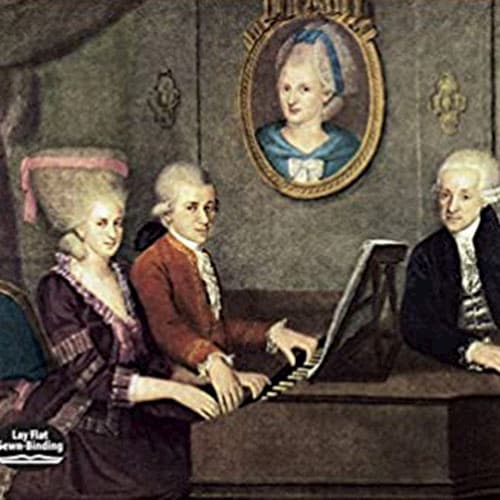

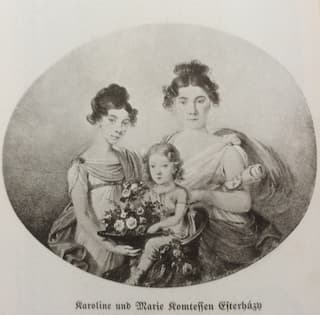

Marie and Karoline Esterházy

It is certainly telling that the earliest surviving music by Franz Schubert is the extended Fantasie D. 48 for piano duet. Composed at the age of thirteen, Schubert composed prolifically for the medium until his untimely death at the age of 31. For Schubert and his friends, four-hand piano music was a natural part of convivial evenings. Since this repertoire was almost exclusively destined for the private amateur salon market, however, a large number of these genial and charming works are still virtually unknown. Presumably written in 1818 or 1824, Schubert’s Variations D. 968a for piano four hands is one of series of compositions written for the two daughters of Count Johann Karl Esterházy. Schubert was engaged as music tutor to the two girls and spent two summers at the Count’s estate at Zseliz in Hungary. Schubert wrote to his friend Moritz von Schwind, “I have composed a big sonata and variations for four hands; the latter are enjoying great applause here, but since I don’t quite trust the taste of the Hungarians I’ll let you and the Viennese decide about them.”

Franz Schubert: Variations in B-Flat Major, Op. 82 (D. 968a)

Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, 1952

Sketched in 1952 and completed in the spring of 1953, Poulenc’s Sonata for two pianos is dedicated to pianists Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale “as much with friendship as with admiration.” Considered one of the most important piano duos of the 20th century, Gold and Fizdale commissioned and premiered a number of important works in the second half of the 20th century, including works by John Cage, Virgil Thomson, and Ned Rorem. As part of the tsunami of American artists, musicians and writers, the Duo traveled to Europe and arrived in Paris in 1948 with a letter of introduction to Germaine Tailleferre. A lunch with Francis Poulenc and Georges Auric was quickly arranged, which in turn lead to a number of works dedicated and composed for the Duo. Tailleferre wrote her Toccata for two Pianos and her Sonata for Two Pianos for Gold and Fizdale, while Poulenc contributed his own Sonata for Two Pianos for “the Boyz,” as he called them. The work was first introduced to the public on 2 November 1953 at London’s Wigmore Hall.

Francis Poulenc: Sonata for Two Pianos (François Chaplin, piano; Alexandre Tharaud, piano)

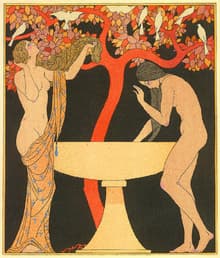

Chansons de Bilitis

Claude Debussy’s friend Pierre Louÿs published his Chansons de Bilitis in 1894. Louÿs claimed that the 143 prose poems were the work of a woman of Ancient Greece called Bilitis, and originally found on the walls of a tomb in Cyprus. Although this amiable case of literary fraud was quickly uncovered, his contemporaries were greatly impressed with the poems skillful and evocative blending of the antique and the modern, and the erotic with the spiritual. In fact, Louÿs sympathetic celebration of “lesbian sexuality earned him sensation and historic significance.” These poems not only inspired 3 operas, but also a number of settings for voice and piano. And Debussy added his three exquisite setting in 1897. To accompany a reading of twelve Bilits poems in 1900, Debussy wrote incidental music scored for two flutes, two harps and celesta. Soon after returning home from a trip to London, which would sadly be his last journey abroad, Debussy returned to his 1900 Bilitis music and reworked it into his Six Épigraphes Antiques for piano four hands. Critics have noted that these, “six pieces capture well the spirit of classical antiquity in cold, marmoreal and simultaneously sensual whole tone scales, modal structures and short repetitive motifs.”

Claude Debussy: Six Épigraphes Antiques (Genevieve Joy, piano; Jacqueline Bonneau, piano)

Brahms Pavillon on Lake Starnberg in Tutzing

Johannes Brahms spent his summer holidays of 1873 on the shores of Lake Starnberg in southern Bavaria. Here he managed to complete a key work in his development towards his first symphony. The Variations on a theme by Joseph Haydn Op. 56 might not actually have been based on a Haydn theme, but they are at the pinnacle of Brahms’s variations craft. In eight dense variations Brahms manages to liberate compositional rationality from any kind of effectual aesthetics. “One cannot just wait for inspiration to turn up,” Brahms once remarked, “but it needs to be earned legitimately, thanks to incessant work.” The original version called for two pianos with Brahms gradually envisioning the work as an orchestral piece. The reason was entirely practical and musical, as the counterpoint eventually becomes so intricate and pervasive that it requires orchestral forces to be heard clearly.

Johannes Brahms: Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56 (Christina Naughton, piano; Michelle Naughton, piano)

The young Beethoven, c. 1780

Cramer’s Magazine of Music dated 2 March 1783 contains the first ever-printed notice pertaining to Ludwig van Beethoven. The correspondent writes, “Louis van Beethoven, son of the tenor singer already mentioned, a boy of 11 years and of most promising talent. He plays the piano very skillfully and with power, reads at sight very well, and I need say no more than that the chief piece he plays is Das wohltemperirte Clavier of Sebastian Bach…. This youthful genius is deserving of help to enable him to travel. He would surely become a second Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart if he were to continue as he has begun.” In 1787 Beethoven was sent to Vienna by the Archbishop of Cologne to take lessons with Mozart. However, the illness of his mother immediately forced his return home to Bonn. Finally in 1792, Beethoven relocated to Vienna to seek his fortunes in the imperial capital. He soon attracted a number of piano students, and he published the didactic Sonata for Piano four hands as Op. 6 with Artaria.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Sonata in D Major for Piano 4 Hands, Op. 6

Ravel, c. 1895

It might come as a surprise that Maurice Ravel originally composed relatively few of his works for orchestra. In fact, some of his most recognized pieces are rearrangements of original piano versions. It has been suggested that Ravel approached composition like a painter approaches a canvas. The piano originals, it has been argued, became the equivalent of a charcoal outline to be colored at a later stage. This is certainly the case with Ravel’s major orchestral tribute to Spain, the Rapsodie espagnole, composed between 1907 and 1908. The origin of this composition was a “Habanera” for two pianos, which Ravel wrote in 1895. It was the first Ravel composition to be performed publicly, and it made a strong impression on Claude Debussy. In 1907, Ravel composed three companion pieces, and by October of that year, the two-piano version was completed. It took Ravel a further 4 months before he had fully orchestrated the work by February 1908.

Maurice Ravel: Rapsodie espagnole (Original 2 piano version) (Louis Lortie, piano; Hélène Mercier, piano)

Eleonor Bindman and Jenny Lin

With the piano taking center stage in the salons and living rooms of the 19th century, music became a widely accepted form of home entertainment. Realizing the full sonorities and orchestral potential of the instrument, it was also a way to actively make and hear music that would otherwise not be accessible. Reductions of chamber music and orchestral works allowed musicians and their audiences to experience a broad range of music. And when two people sit at one instrument sharing space and often the same notes, the interactive side of music making is elevated to a physical level. Composers ranging from Schubert and Brahms and from Rachmaninoff to Debussy made various piano 4 hands arrangements of their own music. Although J.S. Bach also produced a number of arrangements, the time had not yet come to explore the full potential of the piano. As such, a substantial number of composers and performers have taken up this delightful and satisfying task.

Johann Sebastian Bach/arr. E. Bindman: Brandenburg Duet No. 4 (Eleonor Bindman, piano; Jenny Lin, piano)

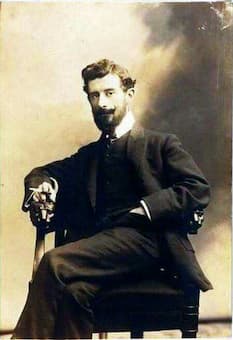

Scriabin

At the age of 16, Alexander Scriabin enrolled at the Moscow Conservatory. His musical talents developed rapidly, and he was mainly regarded as a pianist. A review of a concert on 28 February 1891 reads, “Henselt’s Piano concerto, whose unconventional virtuosic techniques make it one of the most difficult piano compositions, was played by Scriabin, student of Professor Safonov, with such calm and self-assurance that can only be expected from an experienced virtuoso. Scriabin definitely makes huge progress and not only with his technique; his playing is extremely charismatic, having all signs of purely artistic talent.” In addition, Scriabin made his first forays into composition, and that included a Fantasy in A minor for two pianos. Published only after his death, the work is described as “a dazzling exercise in ornated melody built upon a rock-solid harmonic base.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Alexander Scriabin: Fantasy in A minor (Katia Labèque, piano; Marielle Labèque, piano)