It seems like we have a “World Day” for everything these days. From hugging a teddy bear to LGBT Center Awareness Day, the entire spectrum of social causes and cultural cheerleading is filling up our daily calendar. I was very excited to see that November 8 is “World Pianist Day,” and I suspected a century-old tradition of celebration. In the event, it was only established in 2014 by some cultural activists and promoted by the Belarus pianist Alexander Polyakov.

© wall.alphacoders.com

Whatever the motivation, it is still a worthwhile endeavour to celebrate people associated with playing keyboard instruments. In the world of musical instruments, the piano has had a tremendous impact on music, and there are plenty of reasons why playing the piano is a wonderful activity. By celebrating “World Pianist Day,” we decided to pay tribute to all pianists just because playing the piano is a great deal of fun. Just like pianists, the piano repertoire is endless, so we decided to feature a selection of 10 rarely performed piano sonatas.

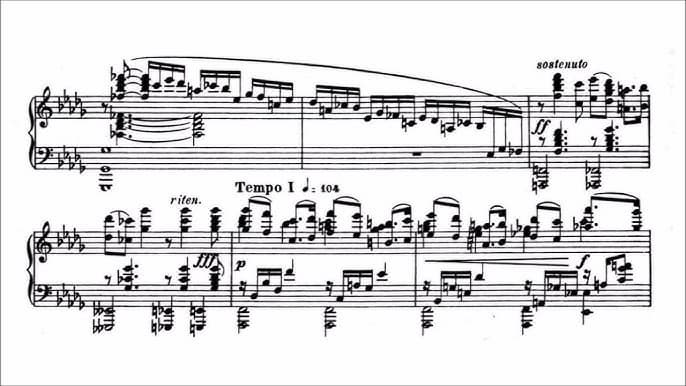

Alexander Glazunov: Piano Sonata No. 2 in E minor, Op. 75

Glazunov’s Piano Sonata No. 2

I’ve decided to start this blog with a work by Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936). To be honest, I have never heard any of the Glazunov piano sonatas in a live recital. Maybe I don’t get out as much as I want to, but the composer has just recently come back onto the pianist radar. Glazunov, we are told, was undoubtedly the most gifted Russian composer of his generation. He certainly was a gifted pianist and his mature piano sonatas date from 1900/01.

His orchestral works were performed with some regularity, even in the West, but his piano sonatas had to first find a place in the repertoire. His second sonata is dedicated to his first piano teacher, Narcisse Jelenkowski, and the opening sequence of simple phrases and a beautifully lyrical second theme provide the musical basket from which the entire work grows. We can certainly hear the organic nature of the work in the final movement, which features a delightful fugal recapitulation.

Felix Mendelssohn: Piano Sonata in G minor, Op. 105

The young Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn: Piano Sonata in G Minor, Op. 105 (Frederic Chiu, piano)

I think we are off to a rousing start with Glazunov, so let’s continue with a big name not generally associated with the piano sonata. Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) needs little introduction, his piano sonatas, however, might. We know that between the ages of 11 and 14, he produced well over a hundred compositions, “a quantity no less astonishing than its variety.” He was young and brilliant and a virtuoso working in a world of extremely finely nuanced sensations. There was an unfailing elegance to his piano works, and this sense of refinement has been frequently confused with superficiality.

One of the early piano sonatas carries the high opus number 105. This simply means that the work was published posthumously and has nothing to do with the year of creation. Mendelssohn simply elected not to see it through to publication. Opus 105 unfolds in three movements, with two monothematic movements framing an expressive and romantic Adagio. And by the way, Mendelssohn was only 12 years old when he wrote this particular sonata exploring the romantic pedal effect. Not only is it an astonishing work from a mere boy, it also sounds like a lot of fun to play.

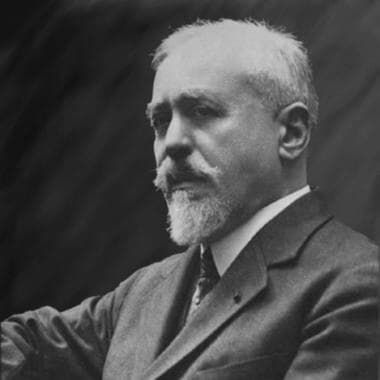

Paul Dukas: Piano Sonata in E-flat minor

Paul Dukas

Paul Dukas: Piano Sonata in E-Flat Minor (Olivier Chauzu, piano)

We all know Paul Dukas (1865-1935) as the composer of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, but did you know that he also composed a vast piano sonata? The seriously grand-scale sonata in E-flat minor is dedicated to Saint-Saëns, and it first sounded in the Salle Pleyel in Paris on 10 May 1901. I think it’s one of the great sonatas of the 20th century, but it is rarely performed. One of the most obvious reasons for a lack of performance is the incredible technical difficulties of the work.

Dukas seems readily inspired by Beethoven, Liszt, and Franck, but the sonata “is really the reflection of Dukas’ own classical and aesthetic thinking, as marked by refined emotion and the discursive density requiring absolute concentration on the part of both the listener and the performer.” I think everything is so highly concentrated that it becomes difficult for audiences to sustain interest and concentration for over 40 minutes. The work is laid out in four movements, and I just love the two themes of the second “Calme, un peu lent, très soutenu.” The two themes are not really in opposition but complementary, and there is a beautiful lyrical progression derived from delicate ornamental variation. If ever this sonata is programmed in my area, I am absolutely sure to go.

Arnold Bax: Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Major

Arnold Bax

Arnold Bax: Piano Sonata No. 4 in G Major (Malcolm Binns, piano)

To tell you the truth, the piano sonatas by Arnold Bax (1883-1953) are a completely new world to me. I’ve never seen them performed on stage, and even trying to get some scores seems to be rather difficult. Bax is primarily known for his symphonies and tone poems, and it seems that pianists don’t associate British composers with solo piano music. However, Bax is actually one of the few British composers who wrote big piano sonatas.

According to pianist Michael Endres, who recorded the complete Bax piano sonatas, “these works require a lot of patience to learn as the composer uses very virtuosic orchestral writing, but the problem certainly isn’t that they are too difficult to play. It is rather the highly charged intensity of his music which demands the utmost in energy from the musician.” I decided to feature the fourth sonata because it is a more light-hearted piece in an almost dance-like style. All the previous sonatas are really big tone poems, but this one is a bit more sober and classical.

Nikolai Medtner: Sonata Romantica, Op. 53, No. 1

Medtner’s Sonata Romantica

I had no idea that Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951) composed 14 piano sonatas in the period between 1895 and 1937. Even more astonishing is the fact that Rachmaninoff told Medtner that he regarded him as the greatest living composer, and Prokofiev wrote in his diaries in 1915, “I love playing Medtner’s Sonatas on the piano, and generally have a great affection for his music, reserving a corner for him in the pantheon of Russian music.” So why isn’t Medtner played much more frequently in live performances?

I think Medtner is actually making a nice comeback after his music had not been well received by critics during his lifetime. Audiences, however, have always loved his music as he had a real affinity with Brahms and combined it with influences from Rachmaninoff, allowing listeners “to know what to expect, and to feel.” For the musical avant-garde, Medtner was a throwback to a bygone era of traditional classical tendency, as his music owes nothing to the influence of the Nationalists or Modernists. Let’s thank him for that, and with 14 piano sonatas to choose from, I better start my listening today.

Nikolai Myaskovsky: Piano Sonata No. 2 in F-sharp minor, Op. 13

Nikolai Myaskovsky

Thankfully, there has recently been more interest in the music of Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881-1950). I read that he was one of those Soviet composers the old communist regime really wished to be silent. As a scholar writes, “he was a musician of unshakable integrity, an introvert who attempted all his life to reconcile his inner being with his outer circumstances, and a conscientiously self-critical composer who strove for an objectivity which he defined as the transmutation of personal experience into universal communication.”

I don’t know if I understand all of this, but I do know that Myaskovsky composed nine piano sonatas, not really published in the order of compositions. And they are certainly not performed with any frequency. His first sonata belongs to the world of Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, and Medtner, and dates from his student years at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. The feature 2nd sonata was revised later and somehow reflects “the excitement of the radical years and presents a strange world filled with conflict.” There are plenty of dissonances and wild fluctuations of tempo and mood, perhaps representing a developed assimilation of Scriabin’s influence and that of the symbolist poets. It is a piece of inner turbulence and rather pessimistic and oozes an air of anxiety throughout. And I just love it!

Leoš Janáček: 1.X.1905

Janáček’s 1.X.1905

I am not sure that I told you, but I just adore the short piano works of Leoš Janáček (1854-1928), some of which I do on occasion hear in concert. However, the one work by Janáček that I have never heard live is his piano sonata with the curious title I.X.1905. As you can tell, the title is actually a date, and it marks the death of a young carpenter by the name of František Pavlík. He had demonstrated in support for a Czech university in Brno and was bayoneted to death.

Initially, the work had a third movement, a funeral march, but Janáček burned that movement shortly before the first public performance. Mind you, the composer was not really happy with the rest of the compositions either and tossed the manuscript into the Vltava river. Janáček later regretted his impulsive action and remarked, “And it floated along on the water that day, like white swans.” Luckily, somebody had made a copy, and the composer provided the following inscriptions: “The white marble of the steps of the Besední dům in Brno. The ordinary labourer František Pavlík falls, stained with blood. He came merely to champion higher learning and has been slain by cruel murderers.”

Jan Ladislav Dussek: Piano Sonata in A-flat major, Op. 64 “Le retour a Paris”

Jan Ladislav Dussek

Jan Ladislav Dussek: Piano Sonata in A-Flat Major, Op. 64/70, “Le retour a Paris” (Markus Becker, piano)

I am not taking anything away from the unbelievable piano sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, but sometimes it would be nice to hear some works by his contemporaries, like Jan Ladislav Dussek (1760-1812). After all, Dussek was one of the most famous and recognized musicians of his time. Dussek, alongside Muzio Clementi and John Field, contributed to the development of the “London” school of pianoforte composition, greatly influenced by the piano manufacture in England.

Dussek composed his “Le retour a Paris” sonata in 1807, whence he returned to the Parisian capital to enter the services of Napoleon’s Foreign Minister Talleyrand. It is a grand and wonderful work that explores the new sonorities and extended range of the piano. But don’t just take my word, as a contemporary critic writes, “ It is a genial product such as are few, one of the most characterful poems that will retain its value as long as music, good pianofortes, and accomplished pianists exist.” A perfect work, it seems to me, to celebrate “World Pianist Day.”

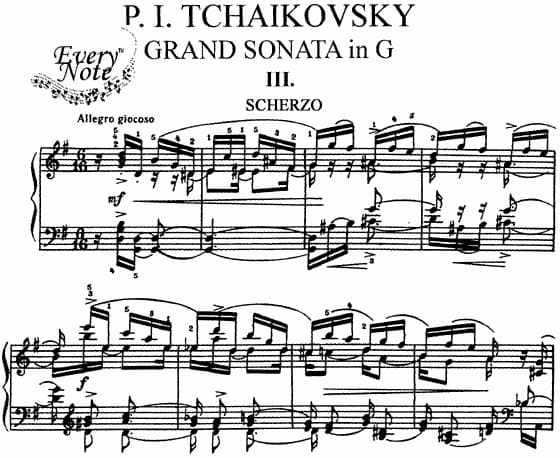

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Grand Sonata in G Major, Op. 37

Tchaikovsky’s Grand Sonata in G

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Grand Sonata in G Major, Op. 37 (Peter Donohoe, piano)

I’d like to conclude this little blog on rarely performed piano sonatas with two composers that really need very little introduction. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) was a good pianist who practised the piano constantly. It’s hardly surprising that he composed a large body of piano music, including a number of sonatas. It’s not easy finding a live performance of the 3 Tchaikovsky sonatas, however, because apparently, “the music does not lie well for the hands and exploits only a narrow range of the piano’s possibilities.” The “Grand Sonata” dates from 1878, and the “author of the fourth symphony and second concerto is instantly and pleasurably recognised.”

Mily Balakirev: Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor

The young Mily Balakirev

There are two reasons why Mily Balakirev (1837-1910) is instantly recognised. For one, he was part of “The Mighty Handful” promoting musical nationalism, and he composed the Oriental Fantasy “Islamey,” still considered one of the most technically difficult works for the piano. Balakirev did compose piano sonatas, but of course, this kind of genre was viewed with great suspicion as it had Germanic associations. In the end, he composed only one completed sonata, and he really tried to be non-Germanic. The opening movement sounds like a highly unorthodox fugal exposition, followed by great lyricism and some kind of mazurka. Scriabin lurks in the “Intermezzo,” and the final movement is of great pianist virtuosity.

Did you enjoy this list of 10 rarely performed piano sonatas? Can you please let us know in your comments which other works you’d like to see featured, and please enjoy the “World Pianist Day.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Excellent, mostly forgotten or unknown ,but very beautiful sonatas.

Thank you

Good, educated choices.

I discovered the 8 piano sonatas of Algernon Ashton, about 15 years ago. I’d recommend them highly for your consideration.

Also, the one sonata of Benjamin Dale. Very Straussian.

And the sonatas of York Bowen.

All from a forgotten era of British pianism.