Wassily Kandinsky: Composition VIII © wassilykandinsky.net

In my article When the Ear Meets the Eye, I mentioned how music and visual arts have collaborated throughout the years, and particularly how composers have taken inspiration in works of visual art to create their own musical works. I conclude that the inspiration goes both ways. Indeed, the intricate language of music has nurtured artists’ creativity for just as long as the opposite has been true. Whether it is in visually including musical concepts, taking inspiration in musical genres and forms, or simply illustrating music.

It is very exciting for an artist to try to translate a form of art into another; in this case, representing a musical concept through the medium of visual art. Kandinsky is of course famous for having created paintings that in his opinion would provide the viewer with a multi-sensory experience. In his Composition 8 (1923), it is the atonality of Schoenberg that is the main subject. Atonality appears as a randomisation of harmony and melody, with tonalities that do not seem to go well together, and it is through a perceived association of random colours that Kandinsky illustrates the musical concept. The colours — and the notes — are in fact very well thought and connected.

Paul Klee: May Picture © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Klee, before succeeding in painting, was a violin prodigy. And this has influenced the artist during his whole career. In May Picture (1925) it is the counterpoint of baroque music that is the foundation of the painting. In musical counterpoint, several voices exchange melodic fragments and development, and through imperfect squares, Klee recreates that exchange of colours and shapes in different parts of the picture.

Just like Feldman did with his work the Rothko Chapel — for the works of Mark Rothko — it is quite common for an artist to pay homage to some of his artistic inspirations.

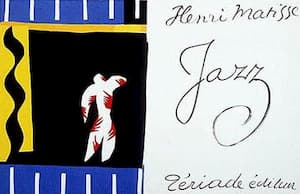

Cover of Jazz by Henri Matisse © Wikipedia

Matisse in his art book Jazz (1947) pays tribute to the improvised music of jazz. It is not in its content that Matisse illustrates how jazz influenced him; indeed it is a book centred around the theme of the circus. It is however in its approach and especially in its spontaneous quality. The publisher, Tériade, suggested the title in order to make the connection between both arts more apparent.

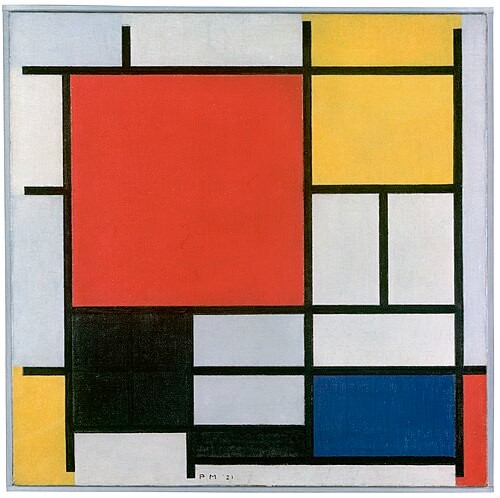

One of the ancestors of jazz, boogie-woogie, is a centre of Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1957) homage. Boogie-woogie is a music that moves away from blues by focusing on dance and movement, and this is exactly what Mondrian’s painting does; based on the city grid of Manhattan it is a work that is full of movement, interconnected lines and rectangular forms of different sizes and colours.

Marc Chagall: Green Violinist © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Painters have repeatedly represented some of their favourite artistic mediums, and that includes of course music.

In the Green Violinist (1924), Chagall represents a fiddler in his misty village. It is the popular and folkloric heritage that the Russian-French artist is representing. Of course, the violin is one of the main instruments of traditional Jewish music, and it is both a way of representing what must have been joyful memories for the painter, as well as a testament of his religious heritage.

In Listening to Schumann (1883), Khnopff does not represent the composer or even the performer, but rather the listener and the effect of the music on her; a deep concentration, isolating herself from the outside world, and perhaps some sort of deep appreciation for the composer’s genius — could it be the other way?

Of course, all arts have inspired and have been inspired by each other. Between two languages of their own, literature and music, for instance. Rachmaninoff and Allan Poe — with The Bells, Debussy — who contrary to popular beliefs did not take his inspiration from the Impressionists but from the poetry of Mallarmé or Verlaine, or more recently Einaudi and Woolf. Even in popular music, literature is and has been a bottomless well of inspiration; Led Zeppelin owes a lot to Tolkien…

When the notes meet the words?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter