Hartmann: Plan for a City Gate

At what must be regarded as one of the most well-known painting exhibitions in music, Modest Mussorgsky’s 1874 piano work Pictures at an Exhibition takes the listener around a gallery of his late friend Viktor Hartmann’s paintings. Hartman died in 1873 of an aneurysm and, seven months later, a memorial exhibition of some 400 works was given at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. Mussorgsky gives us a virtual tour of the exhibition, providing us with music for walking between paintings, the Promenades, and gave us his reflections on a variety of works including costume sketches, architectural sketches, and portraits.

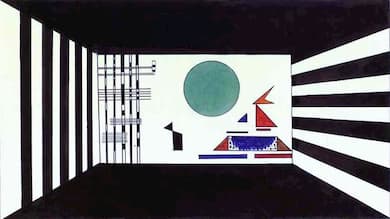

In 1928, Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky used the piano version as the basis for his only theatre work, creating stage designs to go with the music. The images presented below should be imagined as moving – this is the final view, rather than the animated one that the audience would have seen.

Kandinsky’s ideal that the production be a ’Gesamtkunstwerk,’ i.e., a work combing sound, colour, and motion. The work was given its premiere in Dessau, Germany, in 1928. Kandinsky had been living in Dessau since 1922 as a teacher in the Bauhaus school of art and design. The colours used in the designs: light green, white, crimson, black, and ochre, were common Bauhaus colours.

Mussorgsky’s idea in creating Pictures at an Exhibition was not to portray the paintings in music but to ‘portray the impressions left behind.’

The first image picture Gnomus (The Gnome). The image below would have been presented in animated parts and not as the complete image you see here.

Kandinsky: Gnomus

The Old Castle seems to be an image from outside the castle – a tree – a window – a small pavilion?

Kandinsky: The Old Castle

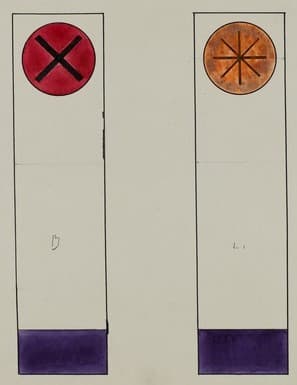

And so we go on. Some of the pictures Kandinsky created move the imagery to the most basic, such as the double portrait of the rich and poor men: “Samuel” Goldenberg and “Schmuÿle”. In Hartmann’s original, these were two separate pictures. In Kandinsky’s realization, he combines them in one image.

Kandinsky: Samuel Goldenberg (Pompidou, Paris)

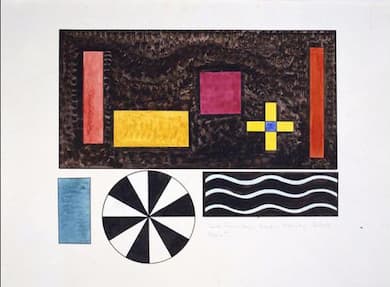

In others, he added decoration not in the music, as in Bydlo, which depicts not cattle but the cart that they are moving.

Kandinsky: Bydlo

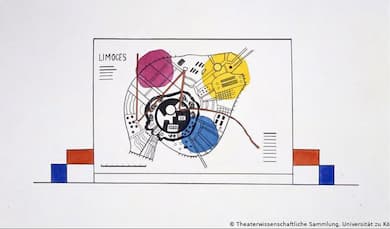

Kandinsky draws us a very literal picture of the Marketplace at Limoges.

Kandinsky: The Marketplace at Limoges

The Roman catacombs place us outside, peering in or inside, peering deeper into the mass of skulls from the past.

Kandinsky: Catacombae

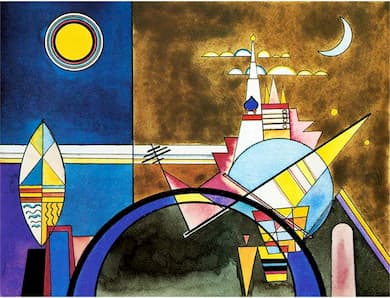

But it is the final Great Gate of Kiev that we’re waiting for and Kandinsky delivers a wild arch, decorated with towers at every angle. He divides the colour vertically, as he did with The Old Castle, making a visual parallel between the two great monuments.

Kandinsky: The Great Gate of Kiev

Kandinsky also supplied an additional set of images for people at the Great Gate.

Kandinsky: Figurines at the Great Gate

A modern reimagining of the original animated stages was created by Felix Klee. Some of the techniques used by Klee could only be accomplished through video manipulation, so this isn’t exactly what you would have seen in 1928 Dessau. Klee did, however, use the preparatory notes prepared by Kandinsky in his work. This reimaging is designed so that each performer determines the delivery of the imagery. The director notes that the pictures are played like an instrument, but one that delivers pictures instead of tones.

Few other artists have taken an approach like Kandinsky’s of going backward in time to re-realize a piano work through the inspiring art work. The net result is that Kandinsky makes us hear Mussorgsky’s tribute to his dead friend in another way – as inspiration to its own new exhibition.