Of all the instruments of the string family, the viola is the butt of most jokes (the Viola player stops for a coffee after a long concert, and is sitting in the restaurant when he realizes that he’s left his viola on the back seat in full view. He rushes out to his car, and his worst fears are confirmed: his back window is smashed, and now there are TWO violas on the back seat.) But the viola is the confident middle voice of the strings. It fills the gap between the soprano violin and the tenor cello. Its size is slightly larger than that of a violin and its voice is lower and deeper than the higher instrument. The violin is tuned a fifth higher than the viola, and the cello is tuned an octave lower.

Viola bridge

Although its role is largely that of support, such as in a string quartet or even in orchestral music, composers have used its lower tone to great effect, such as in Berlioz’s work Harold en Italie. Originally suggested by Niccolò Paganini as a work he could perform on his new Stradivarius viola, he ultimately rejected Berlioz’s piece because there wasn’t enough solo work to satisfy the virtuoso.

Hector Berlioz: Harold en Italie, Op. 16 – I. Harold aux Montagnes. Scenes de melancolie, de bonheur et de joie: Adagio (Wolfram Christ, viola; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

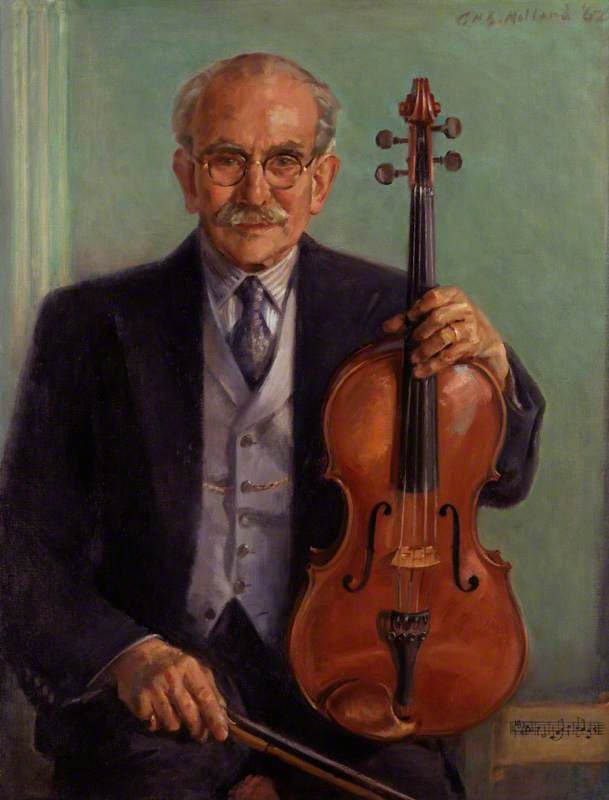

It really wasn’t until the 20th century that viola concertos came into popularity with the appearance of viola virtuosos such as Lionel Tertis and William Primrose. As one writer noted: ‘there are more great violists active today than there are famous viola concertos’.

George Holland: Lionel Tertis, 1962 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

William Primrose holds two violins made for him by William Moennig Jr., 1950

Tertis (1876–1975) started as a violin player and switched to the viola when he attended the Royal Academy of Music in London. Along with teaching at the RAM from 1900, he was also active in string quartets. Composers including Arnold Bax, Frank Bridge, Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Arthur Bliss, and William Walton wrote music for him. Walton wrote his viola concerto for him, but Tertis gave it to Paul Hindemith for the work’s premiere in 1929 at the London Proms. Tertis made his debut with the work in 1930 with Walton conducting.

William Walton: Viola Concerto – II. Vivo, con molto preciso (Nils Mönkemeyer, viola; Bamberg Symphony Orchestra; Markus Poschner, cond.)

Scottish composer William Primrose (1904–1982) also started as a violinist and graduated in violin from the Guildhall School in London. When he went to Belgium to study with the virtuoso violinist Eugène Ysaÿe, he tried one of Ysaÿe’s violas and was encouraged to take up that instrument instead of the violin. He formed the London String Quartet in 1930 and they did international touring; the group disbanded in 1935 due to finances. Primrose moved to New York and became a violist in Toscanini’s NBC Symphony Orchestra. He was encouraged by NBC to form another string quartet and so the Primrose Quartet was formed using other players from the NBC Orchestra.

Benjamin Britten wrote his Lachrymae, op. 48, for Primrose. The subtitle of the work, ‘Reflections on a Song of Dowland’, tells us Britten’s inspiration: A song by John Dowland, ‘If my complaints could passions move’ from Dowland’s First Booke of Songs or Ayres from 1597. This set of variations also includes a brief musical reference to another Dowland song, ‘Flow, my tears’, from the Second Booke of Songs or Ayres of 1600.

Benjamin Britten: Lachrymae, Op. 48, “Reflections on a Song of John Dowland” (Hélène Clément, viola; Alasdair Beatson, piano)

Looking at older composers, Brahms refashioned three of his works for clarinet to the viola. Brahms was inspired by the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld to compose a clarinet trio, a clarinet quintet, and two clarinet sonatas, coming out of virtual retirement to do so. The three works were rewritten with the viola substituting for the clarinet, with some recomposition to better suit the string instrument, including adding double stops and extending the melodic lines.

Johannes Brahms: Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115 (version for viola and string quartet) – I. Allegro (David Aaron Carpenter, viola; members of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra)

German composer Paul Hindemith, himself a violist, wrote his work Der Schwanendreher (The Swan Turner) for viola. In this ‘concerto on old folksongs’, Hindemith chose songs that are about ‘parting, impermanence, loneliness, and grief’ reflecting his difficulties in Germany in 1935: He’d been forced out of the Berlin Conservatory, concert promoters wouldn’t place his works with orchestras, and his works fell out of the repertory. In 1936, Hindemith’s music was officially banned. Hindemith played the premiere of the work in Amsterdam in 1935….but never played it in Germany, from which he emigrated in 1938.

Paul Hindemith: Der Schwanendreher – III. Variations: Seid ihr nicht der Schwanendreher (Geraldine Walther, viola; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Herbert Blomstedt, cond.)

American composer Morton Feldman, in his set of four pieces collectively entitled The Viola in My Life, was inspired by both John Cage and the abstract expressionist painters Rothko, Pollock, and others to try and write music that matched these models. He wanted ‘to find, in music, a language that is equally immediate, direct, physical, and at the same time related to the inexpressible’ that he found in the visual artists’ works. The Viola in my Life IV was commissioned by the 1971 Vienna Biennale and is, in the composer’s words.

Morton Feldman: The Viola in My Life No. 4 (Marek Konstantynowicz, viola; Norwegian Radio Orchestra; Christian Eggen, cond.)

Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu’s work for viola, Tori ga michi ni orite kita (A Bird Came Down the Walk), written for the violist Nobuko Imai, takes its melody from the bird theme in his orchestral work A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden. Takemitsu says of the work, ‘as subtle changes occur in tone colour, the bird theme goes walking through the motionless, scroll painting like a landscape, a garden hushed and bright with daylight.’

Toru Takemitsu: Tori ga michi ni orite kita (A Bird Came Down the Walk) Nobuko Imai, viola; Roland Pöntinen, piano)

The viola has a striking role in music. When we look into the past, we note with interest just how many of the great string quartet composers from the Classical period forward played the viola. In the Austro-Germanic tradition alone, we find Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Dvořák, and, in the twentieth century, Schoenberg and Hindemith, who made the viola one of the instruments they played.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter