Charles-Valentin Alkan

Charles-Valentin Alkan

In our exploration of musical double takes—composers who wrote multiple sets of preludes and/or fugues in all major and minor keys—we have to honour one of the most enigmatic composers in the history of music. Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888) hailed from Paris and quickly established himself as one of France’s leading pianists. A rival of Franz Liszt and close friend of Frédéric Chopin, Alkan is said: “to have been in possession of an almost freighting command of the instrument.” It seems that even Liszt was nervous playing when Alkan was in the house. All this fame none withstanding, Alkan preferred to live the last 20 years of his life as a recluse. In all, Alkan worked on four complete sets, his 25 Préludes dans tous les tons majeurs et mineurs, the Esquisses Op. 63, and the 24 Études were published as separate sets of major-key and minor-key etudes. Apparently, Alkan started a fourth set with his 11 grands préludes et un transcription du Messie de Hændel. This incomplete set of intended 12 pieces is meant to cover all the keys that have one to six flats.

Charles-Valentin Alkan: 25 Préludes dans tous les tons majeurs et mineurs, Op. 31 (Mark Viner, piano)

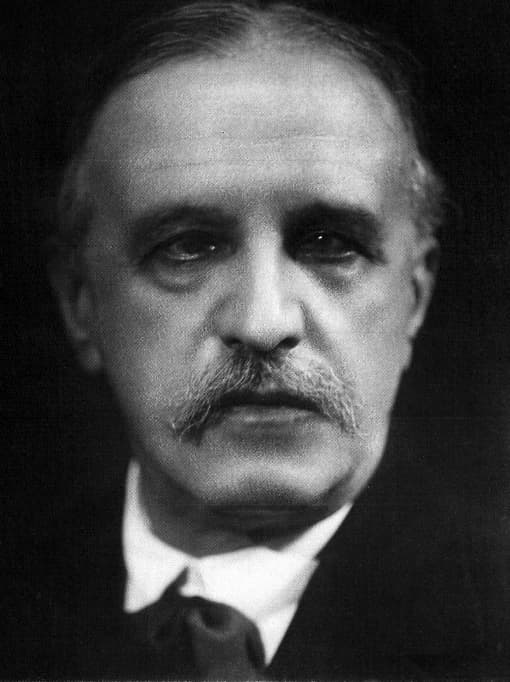

Johann Nepomuk Hummel

Johann Nepomuk Hummel, 1814

Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) was considered one of the greatest composers in Europe in his time. In addition, he had great organizational skills and “created a model for future touring artists.” He had his concerts enthusiastically reviewed in journals owned by his publishers. They praised the “clarity, neatness, evenness and delicacy of his pearly tones and an extraordinary quality of relaxation and the ability to create the illusion of speed without taking too rapid tempos.” Hummel was also one of the most important and expensive teachers in Germany. The young Robert Schumann was desperate to study with Hummel, and Adam Liszt was eager for his son Franz to study with Hummel as well. In the end, neither of them had lessons from Hummel. The Hummel student Ferdinand Hiller reported that his teacher “was primarily concerned that the main voice sings, that the texture be clear and the fingering be secure.” Predictably, Hummel used only his own compositions for instruction, and he fashioned two complete sets of tonally ordered 24 Preludes and 24 Études. He was severely disappointed to read a review of his etudes in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, however, Robert Schumann called them “old-fashioned and not particularly relevant to modern pianists.” That particular circle is organized around the circle of fifths, and “Hummel seems more interested in delicacy, color, expressiveness, emotional directness, and a deep sense of reference for the works of Bach.”

Johann Nepomuk Hummel: 24 Études, Op. 125 (Michael Ponti, piano)

Lera Auerbach

Lera Auerbach © N. Feller

The composer, poet, and author Lera Auerbach was born in Siberia and made her first public appearance at the age of eight. At twelve, she composed an opera and the production toured throughout the former Soviet Union. After her defection to the United States, she attended Juilliard, and in 2000, she was invited by the International Johannes Brahms Society to be composer-in-residence in Baden-Baden. Auerbach has composed 24 Preludes for piano, 24 Preludes for violin and piano, and 24 Preludes for cello and piano. The cello and piano set dates from 1999, and the composer writes, “Re-establishing the value and expressive possibilities of all major and minor tonalities is as valid at the beginning of the 21st century as it was during Bach’s time, especially if we consider the aesthetics of Western music in its regard—or disregard—to tonality during the last century. In writing this work I wished to create a continuum that would allow these short pieces to be united as one single composition. The challenge was not only to write a meaningful and complete prelude that may be only a minute long but also for this short piece to be an organic part of a larger composition with its own form. Looking at something familiar from an unexpected perspective is one of the peculiar characteristics of these pieces, as they are often not what they appear to be at first glance.”

Lera Auerbach: 24 Preludes for Cello and Piano, Op. 47 (Ani Aznavoorian, cello; Lera Auerbach, piano)

Louis Vierne

Louis Vierne, 1915

Louis Vierne (1870-1937) overcame his disability—he was born nearly blind—with a lot of hard work and determination. Following two serious operations in 1877, he was finally able to read large print and he learned Braille in the school for the blind. Vierne showed exceptional musical talents at an early age as he started taking piano lessons at age 2. After studying at the Paris Conservatory, Vierne continued his meteoric rise in the Parisian music scene and he became the assistant of Charles Widor at the Church of St. Sulpice in Paris. To crown his professional career, Vierne was appointed “organiste titulaire” at the Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris, in 1900, soundly beating 50 other applicants in the process. He toured Europe and the United States as a concert organist, and his students included Nadia Boulanger. His compositions primarily focus on the organ, and he put together two sets of pieces in all the major and minor keys. The 24 Pièces en style libre, and 24 Pièces de fantaisie look towards the chromaticism of Richard Wagner and the tone colours of Gabriel Fauré.

Louis Vierne: 24 Pièces en style libre, (excerpts) (Jacques Kauffmann, organ)

Nikolai Kapustin

Nikolai Kapustin © Schott Music/Peter Andersen

The Russian composer and pianist Nikolai Kapustin (1937-2020) has quietly perfected a convincing and idiomatic fusion between the language of jazz and the structural demands of classical music. He was initially trained as a classical pianist, but quickly adopted the performing style of Oscar Peterson. “Skillfully blending and transcending both musical traditions, his compositions present a unique amalgamation of the virtuosity of classical pianism and the improvisational nature of jazz.” At the heart of his compositions is the notion that any music stands to profit from a confrontation with another. Composers of Western art music can learn a great deal from “the rhythmic vitality and swing of jazz, while jazz musicians can find new avenues of development in the large-scale forms and complex tonal systems of classical music.” Kapustin wrote two complete sets of tonally ordered music; the 24 Preludes in Jazz Style of 1988, and his 24 Preludes and Fugues composed in 1997. Chopin greatly influences the 24 Preludes in Jazz Style, “both in their key scheme, which exactly follows Chopin’s model, and in their brevity.” Kapustin follows the jazz practice of stating a melody and then improvising a new melody over the underlying chord structure. Mind you, all of his improvisations are written down and thereby assure us of the intended musical style.

Nikolai Kapustin: 24 Preludes, Op. 53 (Catherine Gordeladze, piano)

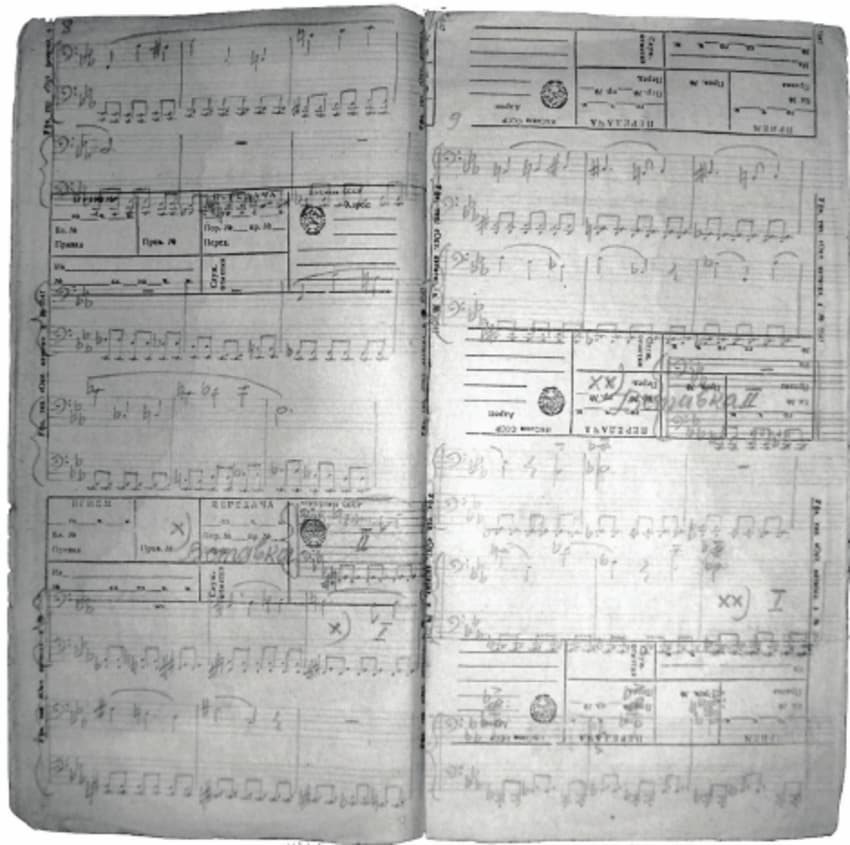

Vsevolod Zaderastsky

Manuscript of two pages from the 24 Preludes and Fugues by Vsevolod Zaderastsky

The Russian composer Vsevolod Zaderastsky (1891-1953) initially studied law and completed a course on military fortifications before attending the Moscow Conservatory of Music. He served in the White Army during the Russian revolution, but dramatically defected to the Red Army “shooting a white officer who was executing red prisoners.” His active revolutionary involvement would spell life-long trouble for the composer. For most of his life, he was blacklisted, and in 1926 Zaderastsky was arrested as a member of the Monarchist movement, and as a propagandist of the fascist music of Wagner and Strauss. He would be in and out of prison throughout his life and he composed his 24 Preludes and Fugues in a prison camp between 1937 and 1939. It is probably the first such attempt in the 20th century.” Zaderastsky did write a second complete set, but many of his papers and manuscripts were destroyed. His compositional legacy came to light only in the 1990s thanks to the efforts of his son, the composer Vsevolod Vsevolodovich.

Vsevolod Zaderatsky: 24 Preludes and Fugues (Jascha Nemtsov, piano)

Friedrich Kalkbrenner

Friedrich Kalkbrenner

When Frédéric Chopin moved to Paris, Friedrich Kalkbrenner (1785-1849) was at the height of his pianist powers. Chopin considered Kalkbrenner the finest pianist he had heard, “Herz, Liszt, and Hiller are all zeros next to Kalkbrenner.” Kalkbrenner was also a famous and very expensive teacher, and Chopin considered becoming his student. Kalbrenner’s reputation as a composer, however, was largely unfavorable. For one, he was firmly set on writing in the Classical tradition and shunned the popular romanticism of composers like Liszt and Thalberg. “His reputation,” a critic writes, “was also impeded by his arrogant and self-indulgent personality that has been the subject of ridicule and novelty up to the present day.” He did, however, compose two complete sets of exercises in all major and minor keys; 24 Études and 24 Preludes. The etudes are musically concise character pieces that are technically useful and the rich variety of characters and colours provide us with one of the most interesting and contrasting sets of studies written.”

Friedrich Kalkbrenner: 25 Grandes études de style et de perfectionnement, Op. 143 (Tyler Hay, piano)

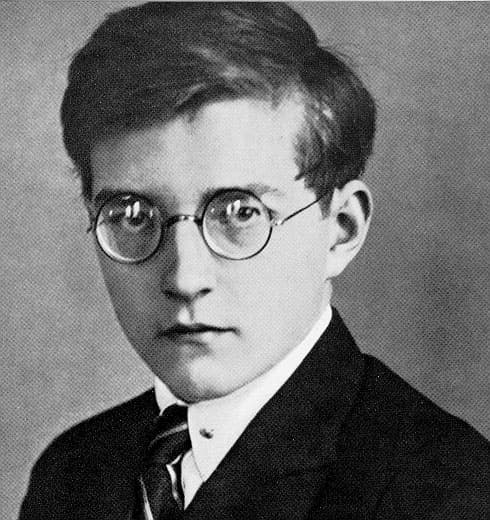

Dmitry Shostakovich

Dmitry Shostakovich, 1925

Let us conclude this short survey on musical double takes with the 24 Preludes by Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975). Shostakovich, as you know, also composed 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87, and he started a project to write 24 string quartets in all the keys. Regrettably, he only completed 15. The opus 34 set was composed in the winter of 1932/33. The strict order of major and minor keys looks towards Bach and Chopin, as do the contrapuntal textures and a highly personal musical style. “Each prelude is sharply etched in mood, with a concentration of effect resulting from an elemental simplicity of texture. The tension in these pieces is between expectation and arrival. Their steady rhythms and predictable phrase structures set up regular surprises for the listener when the melody line or harmonic underpinning so often shocking disagree.” There can be no doubt that complete sets of preludes and/or fugues in all major and minor keys will remain relevant in the 21st century; we are looking forward to many more contemporary musical and stylistic solutions.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Dmitry Shostakovich: 24 Preludes, Op. 34 (Olli Mustonen, piano)