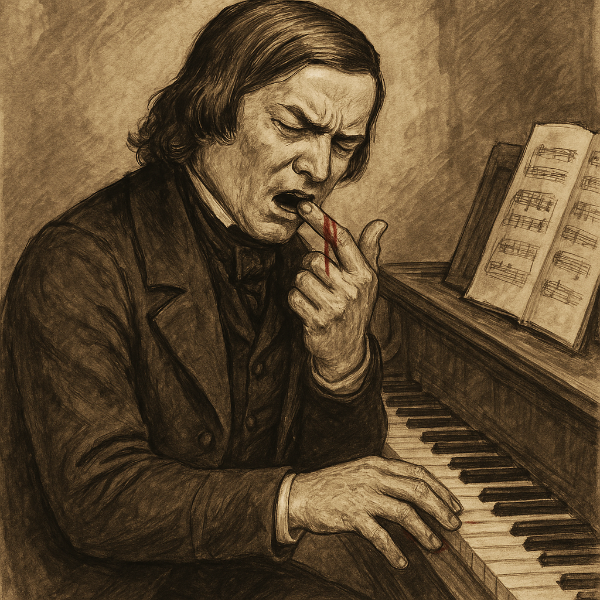

In the early morning hours of 28 December 1937, Maurice Ravel lapsed into a coma and died at the age of 62. He had been troubled by persistent health problems for some time, suffering from insomnia, extensive bouts of depression and difficulties with coordination. Doctors suspected a neurological reason, but the exact cause of his death is still hotly debated.

Grave of Maurice Ravel

Maurice Ravel once declared, “the only love affair I have ever had was with music.” To be sure, Ravel was a meticulous and innovative composer known for his exquisitely crafted compositions. His music blends lush harmonies with intricate textures and vivid orchestrations, communicating refined elegance and sensuousness. Among his most famous compositions, we find Boléro and Daphnis et Chloé, masterworks of orchestral colour, rhythmic complexity, and evocative cinematic soundscapes.

To commemorate Ravel’s passing on 28 December, we decided to feature his concertante works. His two piano concertos are some of his most famous and enduring works in the repertoire, blending virtuosic pianism with lush orchestration, French elegance, and vivid emotional expression. However, let’s get started with Tzigane, a work that originated as a rhapsodic composition for violin and piano, later orchestrated by the composer, and first performed on 19 October 1924.

Tzigane, “Rhapsody for Violin and Orchestra”

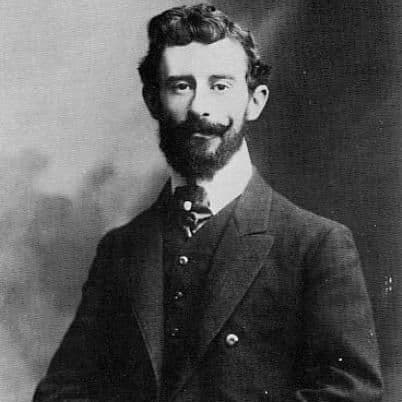

The setting of Tzigane is intimately connected with Jelly d’Aranyi, a gifted violinist and the great-niece of the influential violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim. Her Hungarian heritage and vibrant personality captivated a number of composers. Béla Bartók wrote two violin sonatas for her, and both Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst dedicated concertos to Jelly.

Jelly d’Aranyi

Ravel first met her in London in 1922. Apparently, the composer was enamoured with her playing and persuaded her to perform gypsy melodies for him late into the night. Inspired by this, Ravel promised to write a violin piece for her, describing it as a “short piece of diabolical difficulty” reflecting the Hungary of his dreams.

Ravel worked closely with Jelly while composing Tzigane, frequently consulting her on technical matters and violin techniques. He even asked her to help with some of the more challenging passages. To enhance the “tzigane” flavour of the work, Ravel specified the use of a luthéal (a special piano attachment) to imitate the sound of a cimbalom, a traditional Hungarian instrument.

Jelly received the score only four days before its London premiere in 1924, and some listeners wondered if Ravel’s Tzigane might be a musical parody. However, Ravel’s sincerity in capturing Hungarian folk music was clear. Despite not being a violinist himself, Ravel’s composition was idiomatically correct, and he later orchestrated the piano part for orchestra.

Maurice Ravel

Ravel certainly wasn’t exaggerating when he talked about “diabolical difficulties.” The piece opens with a free improvisatory cadenza, creating a wonderful atmosphere of spontaneity and flair. Rhythmic vitality, frequent use of modal scales, and ornamentation such as trills and grace notes evoke the “tzigane” style. Harmonically, Ravel employs rich, shifting tonal colours, often using dissonance and unresolved harmonies. The second section transitions into a lively, fiery dance, demanding immense technical skills from the performer. Ravel showcases expressive depth and technical prowess throughout, culminating in a thrilling conclusion.

Piano Concerto in G Major

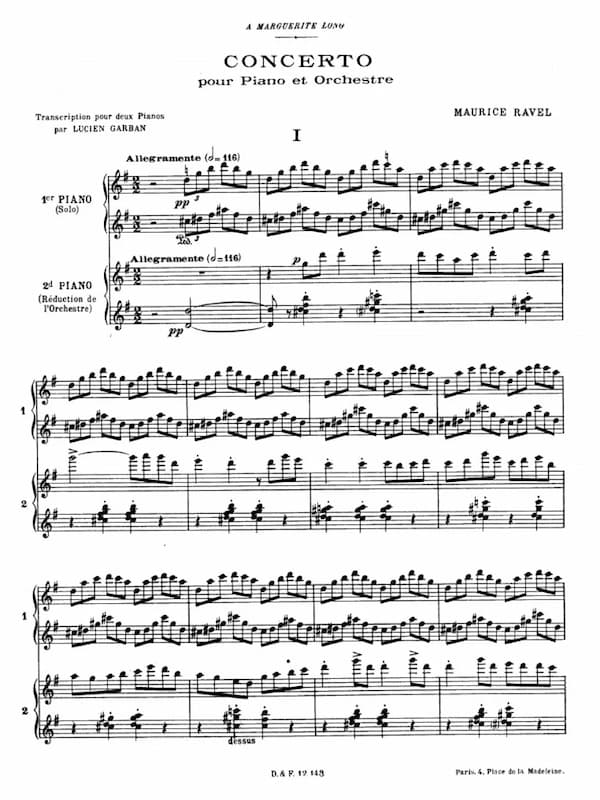

Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G Major

Maurice Ravel: Piano Concerto in G Major, “Allegramente” (Pascal Rogé, piano; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra; Bertrand de Billy, cond.)

After months of careful planning, Maurice Ravel embarked on a 4-month tour of North America in 1928. In all, he visited 25 cities coast-to-coast and performed and conducted the leading orchestras of Canada and the United States. He certainly was fascinated by the dynamism of American life and admired “the huge cities, skyscrapers, and its advanced technology.”

Musically speaking, Ravel was much impressed by jazz, Negro spirituals, and the excellence of American orchestras. Ravel once commented that he preferred jazz to grand opera and remarked, “The most captivating part of jazz is its rich and diverting rhythm… Jazz is a very rich and vital source of inspiration for modern composers, and I am astonished that so few Americans are influenced by it.”

Once he had returned to Europe, Ravel began to encode his jazz impressions into a buddying piano concerto. As he explained, “The G-major Concerto took two years of work. The opening theme came to me on a train between Oxford and London. But the initial idea is nothing. The work of chiselling then began. We’ve gone past the days when the composer was thought of as being struck by inspiration, feverishly scribbling down his thoughts on a scrap of paper. Writing music is seventy-five per cent an intellectual activity.”

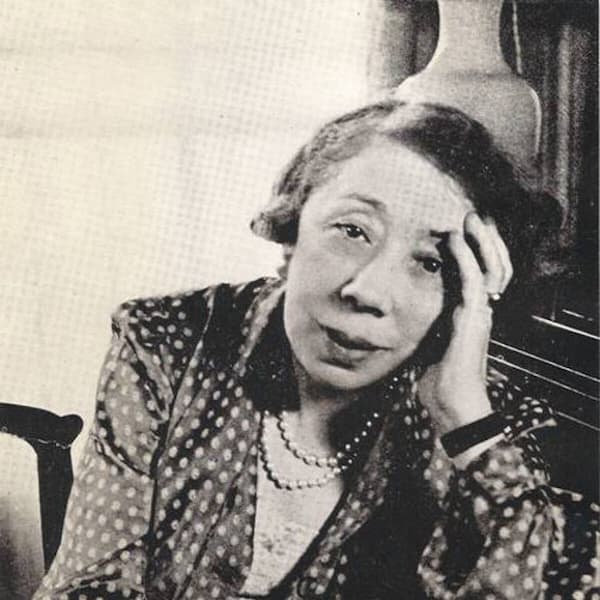

Marguerite Long

Ravel was eager to play the premiere, but he was struck down by a number of health problems. A further attempt to introduce the work to the public on 9 March 1931 in Amsterdam had to be cancelled because he was under pressure to complete the commissioned piano concerto for left hand for Paul Wittgenstein. In the end, Marguerite Long played the premiere with Ravel conducting on 14 January 1932.

Maurice Ravel: Piano Concerto in G Major, “Adagio Assai” (Pascal Rogé, piano; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra; Bertrand de Billy, cond.)

The first movement, “Allegramente”, opens with a sharp crack, setting a playful tone. Syncopated rhythms, strong percussion, and bold brass create a jazz-infused atmosphere. The piccolo leads a lively melody, later joined by the piano with a contrasting lyrical theme. Jazz elements, such as blue notes and syncopation, appear throughout. A slower, dreamy section follows, featuring harp and percussion, before the piano delivers a complex cadenza. The movement ends with a lively reprise of earlier themes.

The second movement contrasts sharply with the first, offering a more introspective, lyrical quality. It begins with a lengthy piano solo, presenting a theme that is nostalgic and bittersweet yet tranquil in its beauty. The theme is passed between the piano, woodwinds, and strings, with the piano taking on a supportive role. A particularly poignant moment occurs when the English horn presents a simple, expressive aria before the theme circulates through the orchestra. As the music unfolds, the mood becomes more subdued, ultimately fading into silence, creating a moment of serene reflection.

The “Presto” reprises the lively spirit of the first movement with heightened intensity and virtuosity. It begins with a brass fanfare, signalling a dynamic race between piano and orchestra. The piano introduces a perpetuum mobile theme, followed by a brass-led second theme resembling hunting horns. A dramatic duo between piano and bassoons highlights the musical contest. Rapid motivic fragments, recalling blue notes, build to a brisk, energetic conclusion infused with jazz influences and Ravel’s rich harmonies.

Ravel masterfully blends elements of jazz and classical music, with the piano serving not only as a solo instrument but also as an integral voice within the orchestra. The rhythmic complexity, orchestral colour, and jazz-inspired motifs demonstrate Ravel’s ability to fuse his European classical training with the new sounds he encountered in America, resulting in a work that is both innovative and deeply expressive.

Maurice Ravel: Piano Concerto in G Major, “Presto” (Pascal Rogé, piano; ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra; Bertrand de Billy, cond.)

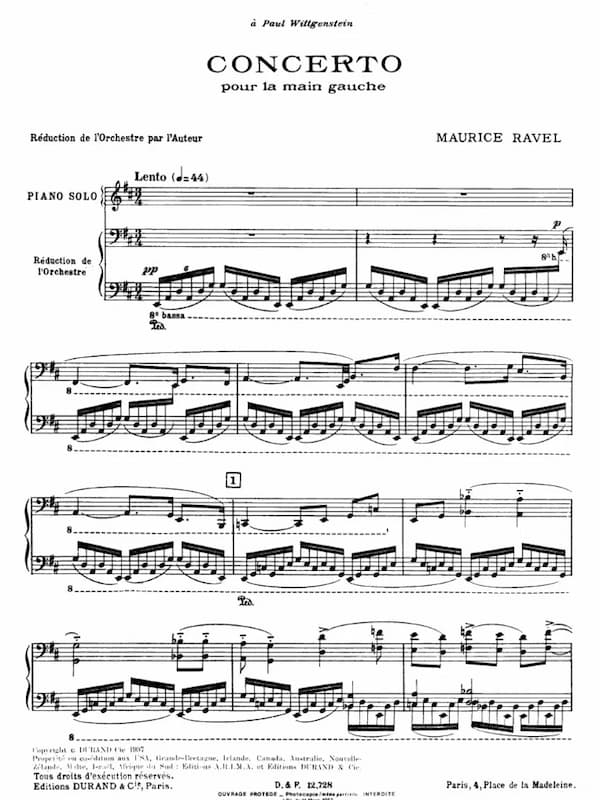

Concerto for the Left Hand

Paul Wittgenstein

The story of Paul Wittgenstein is a remarkable narrative of resilience, artistic dedication, and a deep commitment to his craft, set against the backdrop of World War I and the dramatic transformation of his career. Serving in the Austrian army, Wittgenstein was severely wounded by a sniper’s bullet, which led to the amputation of his right arm. This injury would be a pivotal moment, as it forced him to reinvent himself not just as a pianist but as a pianist who could only play with his left hand.

Once he returned to Vienna, Wittgenstein began the painstaking process of searching for repertoire suitable for the left hand, combing through music libraries and second-hand stores. Moreover, he commissioned works specifically for the left hand from some of the most prominent composers of the day, including Maurice Ravel, who would write one of the most famous concertos for the left hand.

In 1929, Wittgenstein commissioned Ravel to compose a concerto for the left hand. Initially unimpressed, Wittgenstein later appreciated the work’s brilliance. The concerto premiered on 5 January 1932, with Wittgenstein as soloist. However, tensions arose when Wittgenstein made modifications to the score to improve playability with one hand. Ravel, visiting later with Marguerite Long, confronted Wittgenstein over the changes, strongly opposing any alterations to the original composition, leading to a tense disagreement between them.

The tension between Wittgenstein and Ravel over the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand stemmed from their differing views on musical interpretation. Wittgenstein, emphasising artistic freedom, sought to make adjustments for his own virtuosity, while Ravel, a meticulous composer, insisted on strict adherence to the score. Despite their disagreements, the concerto was performed in Paris in 1933 with Ravel conducting, symbolising a reconciliation, though Ravel’s dissatisfaction with Wittgenstein’s changes likely persisted.

Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

The concerto is a single-movement work in three sections, primarily scored for low-pitched instruments to create a sombre and heroic tone. The “Lento” prelude leads to a dramatic piano cadenza, followed by a lively, jazz-influenced “Allegro,” blending American blues and Iberian styles. The final cadenza revisits all themes, culminating in a brilliant coda. Ravel’s orchestration and thematic development showcase both technical mastery and emotional depth throughout the piece.

As one of his dearest and closest friends, the exceptional pianist Marguerite Long, wrote, “Maurice Ravel is reserved, sacred, and distant, but he was the surest, most delicate, and most faithful of friends. By his exterior appearance, his witticisms, and his love of paradoxes, he has often contributed to crediting the myth of spiritual indifference, but, in spite of these appearances, this great prisoner of perfection hid a sensitive and passionate soul.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter