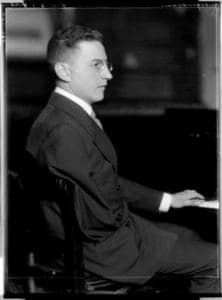

Paul Wittgenstein

The promising career of pianist Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961), older brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was seemingly cut short by events of World War I. Paul had given his debut recital in December of 1913, an event that was enthusiastically reviewed by Max Kalbeck in the Neues Wiener Tageblatt. Kalbeck writes, “A young man from Viennese Society, who in 1913 introduced himself to the public as a piano virtuoso with a Concerto by Field, must either be a fanatical enthusiast or a very self-conscious dilettante. Now, Paul Wittgenstein, for it is of him we speak, is neither the former nor the latter, but more than both of these: He is a serious artist!”

Wittgenstein and Ravel

Having studied with the Viennese pedagogue Malvine Brée and subsequently the famed Theodore Leschetizky, Wittgenstein was well on his way of making a name for himself on the musical stage. However, with the outbreak of World War I, Wittgenstein was conscripted into the Austrian army and sent to the Polish front. On reconnaissance patrol, he was severely wounded on the elbow by a sniper. Transferred to a hospital in Krasnostov, his right arm had to be amputated in the summer of 1914. While a patient, he was taken prisoner by the Russian army and transferred to hospitals in Minsk and Orel, and finally to a prison camp in Omsk, Siberia. During his interment in Omsk, Wittgenstein confided in his former composition teacher, the blind Viennese composer Joseph Labor, that he was determined to continue his pianistic career.

Wittgenstein’s family in Vienna, 1917

Wittgenstein’s father, the industrialist Karl Wittgenstein, was part of the cultured bourgeoisie in Vienna. He had made huge amounts of money in the railways and steel business, and patronage in the arts became his all-consuming passion. He generously supported the “Wiener Werkstätte,” his daughter was painted by Gustav Klimt, and Gustav Mahler, Clara Schumann, Pablo Casals, Bruno Walter and Johannes Brahms were frequent visitors to the Wittgenstein’s Red Salon. When he died on 20 January 1913 of a massive heart attack, he left “one of the largest fortunes in the world” to his family. Once Paul returned to Vienna in 1918 he searched for suitable repertoire for left hand in libraries, museums and second-hand music stores, and he began to fashion hundreds of arrangements of piano works and operatic arias. However, in order to complete his successful transformation into a left-hand virtuoso, Wittgenstein was in need of a suitable chamber and concert repertory. His considerable financial inheritance allowed him to commission dedicated works from the leading composers of the day, including Maurice Ravel.

Wittgenstein Plays Ravel

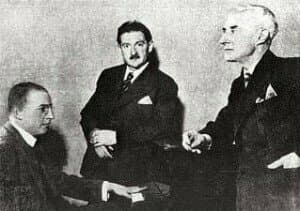

Ravel and Marguerite Long

Wittgenstein commissioned Ravel for a concerto for the left hand in 1929. At that time, Ravel was already working on his G Major concerto, and he was clearly intrigued by the challenges a left-hand concerto would pose. Ravel introduced the concerto to Wittgenstein by playing the solo part with both hands, followed by a piano reduction of the orchestral score. Wittgenstein was initially not impressed and voiced his reservations. The pianist later stated, “Ravel’s pianism had negatively influenced my original perception, and it was not until I had studied the score extensively that I recognized the stature of the work.” In the event, the concerto premiered on 5 January 1932, with Wittgenstein as the soloist and Robert Heger conducting the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Ravel was unable to attend the premiere, but together with Marguerite Long visited Wittgenstein at the end of January 1932.

Maurice Ravel

Long had been told that Wittgenstein had made certain changes to the score, and she relates the following anecdote. “During the performance, I was following the score of the Concerto, which I did not yet know, and I could read our host’s enterprising faults on Ravel’s face, which became increasingly somber. As soon as the performance was over, I attempted a diversionary tactic with ambassador Clauzel, in order to avoid an incident. Alas, Ravel slowly walked towards Wittgenstein and said to him: ‘But that’s not it at all!’ He defended himself: ‘I am a veteran pianist and it doesn’t sound well!’ was the reply. That was exactly the wrong thing to say. ‘I am veteran orchestrator and it does sound well,’ replied Ravel. One can imagine the embarrassment! I could not calm Ravel, who later on opposed Wittgenstein’s coming to Paris. Justly furious, the latter wrote to him: ‘Interpreters do not have to be slaves,’ and Ravel answered him ‘Interpreters are slaves.’

Paul Wittgenstein © BFMI

A couple of months after Ravel’s visit, on 7 March 1932, the composer sent a formal and legally binding contract to Wittgenstein, demanding that his work was henceforth to be played strictly as written. Wittgenstein replied as follows. “As for a formal commitment to play your work henceforth strictly as it is written, that is completely out of the question. No self-respecting artist could accept such a condition. All pianists make modifications, large or small, in each concerto we play. Such a formal commitment would be intolerable: I could be held accountable for every imprecise sixteenth note and every quarter-rest which I omitted or added… You write indignantly and ironically that I want to be ‘put in the spotlight.’ But, dear Maître, you have explained it perfectly; that is precisely the special reason I asked you to write a concerto in the first place. Indeed, I wish to be put in the spotlight. What other objective could I have had! I therefore have the right to request the necessary modifications for this objective to be attained… As I wrote to you, I only insist upon several of the modifications, which I proposed to you, not all of them: I have in no way changed the essence of your work. I have only changed the instrumentation. In the meanwhile, I have refused to play in Paris, as I cannot accept impossible conditions.” In the end cooler heads prevailed and Wittgenstein introduced the concert to Paris on 17 January 1933, with Ravel conducting.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Maurice Ravel: Concerto for the Left Hand

Thank you for this interesting piece. To be frank, I’ve always considered the left hand concerto a bit boring. But yet impressive ..

My question is, however: who decided what to play after the heads had cooled down?

Great story. Thank you.