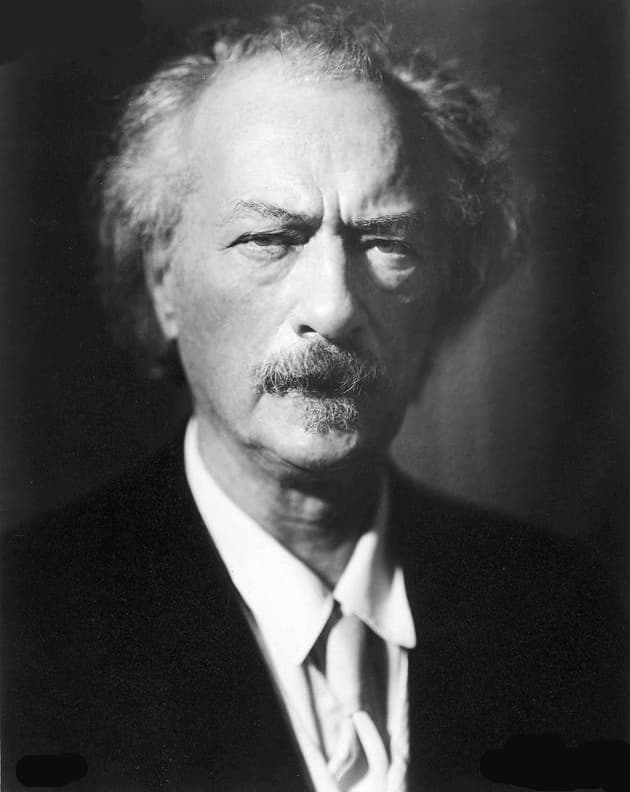

The pianist Ignacy Paderewski (1860-1941) was a favorite with concert audiences but not universally beloved by music critics. In the event, Paderewski was much more than just a rich, irresistibly handsome, wild-haired composer and musician whose concerts generated a level of excitement not seen since the heydays of Franz Liszt.

Monument of Ignacy Jan Paderewski in Warsaw, Poland

The artist was a polymath, philanthropist, monument builder, winemaker, and Poland’s Prime Minister during a period in which he signed the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called him a “Modern Immortal,” and borrowing that title an author later wrote “Paderewski is a superlative man, and his genius transcends that of anyone I have ever known. Those of us who love Poland are glad that she can claim him as a son, but let her always remember that Ignacy Jan Paderewski belongs to all mankind.”

Ignacy Paderewski: Nocturne in B-flat Major, Op. 16, No. 4

The director of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute wrote in 2016, “Paderewski is a figure that should unite us all—right-wing, left-wing, upper or lower wing. He wasn’t a saint, but he represents values cherished by all of humanity; he was hard-working, patriotic, inventive, humble, eager to be of public service rather than trying to enrich himself or grab power.” The American poet John H. Finely had previously addressed the following lines to Paderewski:

Ignacy Paderewski

Your touch has been transmuted into sound

As perfect as an orchid or a rose,

True as a mathematic formula

Yet full of color as an evening sky.

But there’s a symphony that you’ve evoked

From out of the hearts of men, more wonderful

Than you have played upon your instrument…

Paderewski was an artist of such “a distinctly pronounced individuality as to be an exceedingly rare occurrence, indeed phenomenal. He was a beautiful orator in a language that was not his, a linguist who spoke no less than seven languages fluently, but most of all a humanitarian who was so generous that every act of kindness to him was always returned manifold.” Paderewski inspired politicians and musicians alike, and various acts of kindness were indeed returned to him in the form of musical dedications. Let us explore some musical compositions inspired and dedicated to the phenomenon Paderewski.

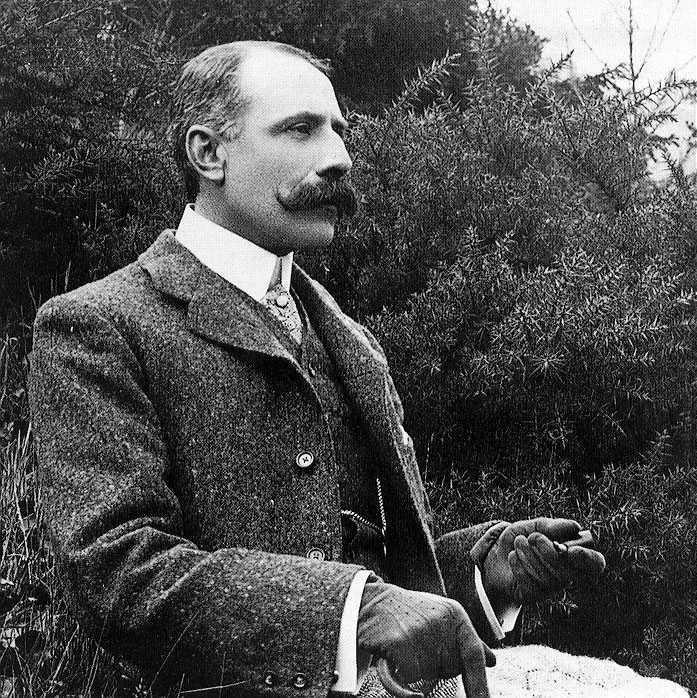

Edward Elgar: Polonia

Edward Elgar

Edward Elgar: Polonia, Op. 76 (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Andrew Davis, cond.)

In 1915, the conductor and composer Emil Młynarski, Music Director of the Scottish Symphony Orchestra, asked Edward Elgar for a work for the Polish Victims Relief fund. That Relief Fund was a worldwide effort, organized by Paderewski and Henryk Sienkiewicz, in aid of refugees from the conflict between the forces of Russia and Germany raging on Polish territory. Elgar writes to Paderewski, “For the Polish Concert in July, I composed an orchestra piece ‘Polonia’ as a small personal tribute to you; founded upon some Polish themes the work had success: in the middle section I have brought in remote & I trust with poetic effect a theme of Chopin & with it a theme of your own from the ‘Polish Fantasia’ linking the two greatest names in Polish music – Chopin & Paderewski. I hope that you will one day hear the piece &, it may be, approve.” Paderewski heard the work in October and responded, “I heard your noble composition, my beloved ‘Polonia,’ on two different occasions: deeply touched by the graciousness of your friendly thought, and profoundly moved by the exquisite beauty of your work, I write you this letter of sincere and affectionate appreciation.”

Zygmunt Stojowski: Piano Concerto No. 2 in A-Flat Major, Op. 32

Zygmunt Stojowski in 1916

Zygmunt Stojowski: Piano Concerto No. 2 in A-Flat Major, Op. 32 (Witold Wilczek, piano; Jerzy Semkow Polish Sinfonia Iuventus Orchestra; Marek Wroniszewski, cond.)

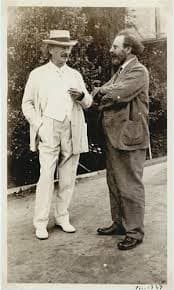

A good many critics and commentators consider Zygmunt Stojowski (1870-1946) the “missing link between Frédéric Chopin and Karol Szymanowski, a composer who shaped Polish music between the second half of the 19th century and the dawn of modernism.” Stojowski’s compositions never managed to enter the repertoire, and their fate epitomizes “Poland’s position as a pawn in the hands of the political and cultural powers and a search for autonomy and identity.” The emergence of a Polish national sentiment was of great importance to Stojowski, who credits Paderewski as being “the foremost influence upon his development.” He later wrote, “When I was a lad I met Paderewski at my mother’s house at the time when he appeared in Cracow in recital for the first time. I feel proud now when I recall that I then had a subconscious feeling of Paderewski’s greatness before the world knew it and before I could consciously realize it myself. Later on, in Paris, I met Paderewski again, and it was he who, several years after my graduation from the Consérvatoire, turned my activity back to the piano after it had for a time been devoted largely to composition. He pointed out to me that it was foolish to let go and waste the pianistic equipment on which I had spent so much energy in my early days. He made me see the good sense of utilizing its earning power. You know, composition is a career of luxury, as an old copyist said to me when I objected to the high charges in his bill.” Stojowski’s Piano Concerto No. 2 is dedicated to Paderewski, and it sounded alongside Elgar’s Polonia at Carnegie Hall in 1916.

Ignacy Paderewski and Zygmunt Stojowski shared a friendship that lasted almost fifty years. Stojowski was studying in Warsaw with Władysław Żeleński, but soon began taking lessons from Paderewski, who was ten years his senior. According to an anecdote, Paderewski instructed his student on the importance of practice, self-criticism, and attention to the quality of tone. Supposedly Paderewski said, “ “No doubt you feel the beauty of this composition, but I hear none of the effects you fancy you are making.” And Stojowski cited Paderewski as saying, “a great performance should have the spontaneous quality of an improvisation, but the achievement of this goal is only possible through painstaking effort including hours of practice in slow tempi and music analysis of minute details of the composition. Only full analytical knowledge and physical mastery of the mechanics of the piece of music would result in a perfectly executed performance.” In later years, Paderewski wrote a letter of recommendation for Stojowski praising “a pedagogue who had adopted the master’s method and who had no superior.”

Zygmunt Stojowski: Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op. 21

Igancy Jan Paderewski and Zygmunt Stojowski

Zygmunt Stojowski: Symphony No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 21 (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Antoni Wit, cond.)

In 1900, Paderewski established the “Igancy Jan Paderewski Trust,” basically a series of financial prizes for works by American composers. Money was awarded for the best symphonic and best chamber music. Paderewski had established a similar fund for composers in Leipzig in 1898, and Zygmunt Stojowski entered his Symphony in D minor, Op. 21. The work was awarded the first prize, and the 28-year-old composer also received a substantial amount of prize money. The jury, under the chairmanship of the conductor Arthur Nikisch, awarded the prize unanimously but did ask that the final movement be revised. Once the revisions had taken place, the Symphony was dedicated to Paderewski and premiered on 15 November 1900 with the Berlin Philharmonic. The Polish premiere took place in Warsaw one year later, and C.F. Peters published the work in 1901. For the jurors, “Stojowski had a strong gift for melody and a deft hand at colorful instrumentation.” And for a good many commentators, Stojowski “created one of the most important Polish contributions to the genre of the symphony.”

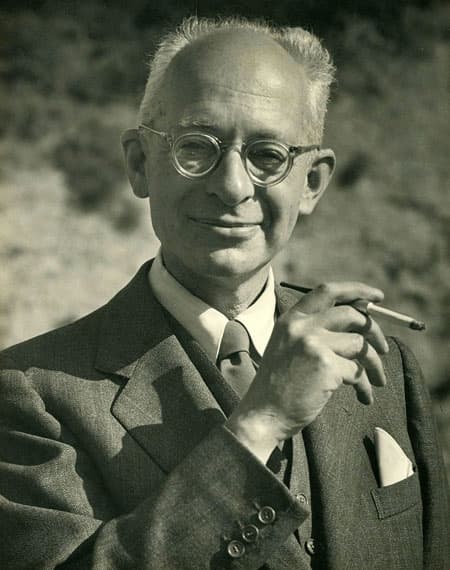

Eugene Goossens: Homage to Paderewski

Eugene Goossens

Eugene Goossens: Homage to Paderewski (Antony Gray, piano)

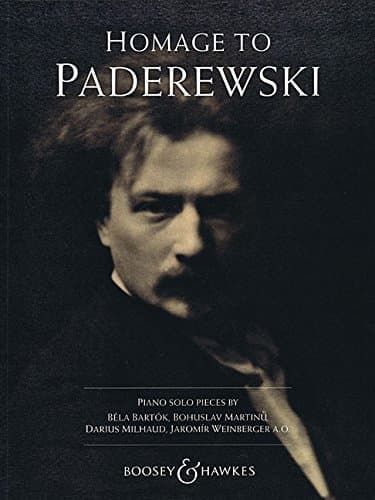

Paderewski first appeared in New York City, in the newly built Carnegie Hall, on 17 November 1891. The NY Times excitedly wrote, “no pianist has made such a sensational impression since Anton Rubinstein.” Seats had to be added on stage to accommodate all of his adoring fans, and he played no fewer than 11 solo piano recitals at that venue, all part of a grueling 117-concert American tour. As has been written, “his tangle of flaming hair, his passionate gesticulations, and his innate charisma incited the type of riots that would later be reserved only to pop and movie stars.” In 1941, the publisher Boosey & Hawkes planned an anthology of piano pieces by 17 contemporary composers to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Paderewski’s American debut. However, as the pianist had sadly died on 29 June, it was eventually published as a memorial edition.

Bohuslav Martinů: Mazurka, H. 284 “Hommage to Paderewski”

Bohuslav Martinů

Bohuslav Martinů: Mazurka, H. 284, “Hommage to Paderewski” (Giorgio Koukl, piano)

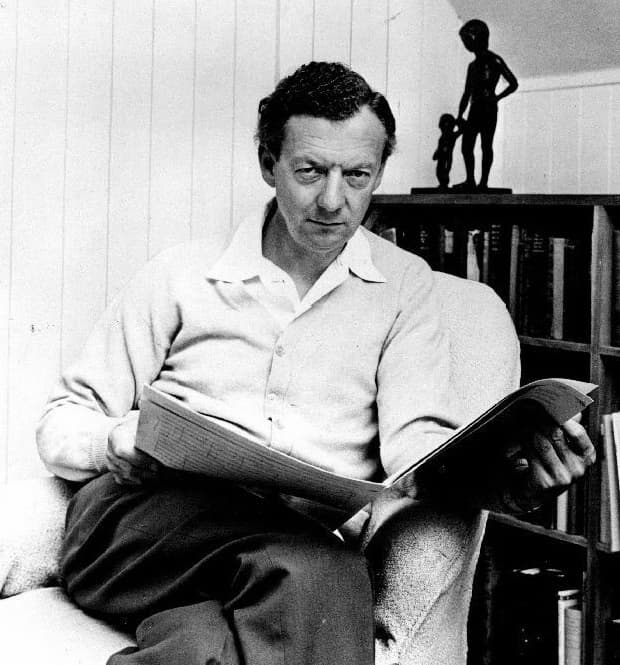

In all, twenty-one composers submitted 22 works, and 17 were chosen for publication. Of these 17 composers, only three were native-born Americans. The remainders had either settled in North America or were working there temporarily in the United States, such as Benjamin Britten and Eugene Goossens.

Béla Bartók: Three Hungarian Folk-Tunes

Béla Bartók: 3 Hungarian Folk Tunes, Sz. 65-66 (Jenő Jandó, piano)

Béla Bartók was living in the US at the time and wished to return to his native Hungary at the end of the war. Sadly, he died before he could make his journey home and his Three Hungarian Folk-Tunes actually date from between 1914 and 1918.

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Homage to Paderewski

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Homage to Paderewski (Pietro Massa, piano)

Although born in Italy, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco settled in California. He is known as one of the foremost guitar composers with almost one hundred compositions for that instrument to his name. He also composed music for some 200 Hollywood movies, and wrote dedicated concertos for Jascha Heifetz and Gregor Piatigorsky. His musical tribute “Hommage à Paderewski” is a tender mazurka with a strange cadenza-like passage before the end. A critic writes, “Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s “Hommage à Paderewski” channels this composer’s cosmopolitan, harmonically sophisticated style through the filter of a Chopin Mazurka, yet makes a couple of Debussy-like detours.”

Benjamin Britten: Mazurka elegiaca, Op. 23, No. 2

“Homage to Paderewski”

Benjamin Britten: Mazurka elegiaca, Op. 23, No. 2 (Stephen Hough, piano; Ronan O’Hora, piano)

Also included in the set are miniatures by Felix Labunski, whose studies in Paris with Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger were financed by Paderewski. The internationally famous pianist Joaquin Nin-Culmell was born in Berlin of Cuban ancestry and immigrated to the United States in 1939. Karol Rathaus was born in present-day Ukraine and also departed for the United States, as did Alexandria, Egypt-born Vittorio Rieti. Ernest Henry Schelling was a child prodigy who made his debut at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia at the age of 4. Already at age 7, he was on his way to Europe and admitted to the Paris Conservatoire. At the age of 20, in 1896, Schelling began his studies with Paderewski and subsequently toured Europe and North and South America. Schelling died of a cerebral embolism at his home in New York City, and Paderewski was greatly affected by his death. Schelling’s widow submitted her husband’s last composition “Ragusa” to the Paderewski tribute.

Hans Wild: Benjamin Britten, 1968

Apparently, Benjamin Britten misunderstood the commission and wrote a piece for two pianos. Be that as it may, it was published separately but is still considered part of the tribute volume. A critic wrote, “There are no notes to spare in Mr. Britten’s music. The three sections of this somber Mazurka make their appeal bluntly and boldly and show the composer’s remarkable capacity for judging just how his score is going to tell in the concert hall. He has no use for elaborate detail nor does he burden the performer with technicalities, which the listener can seldom be expected to grasp.”

Cécile Chaminade: Etude symphonique, Op. 28

Cécile Chaminade

As a pianist, Paderewski exerted a tremendous influence on contemporary virtuoso performers and composers. Among them was Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944), who composed four études to which she attached adjectival descriptors: mélodique, romantique, symphonique, and pathétique. And it is the “Étude symphonique” that is dedicated to Paderewski. Relying on complex cross rhythms that contrast patterns of two against three, or three against four, Chaminade was described,“ as belonging essentially to the French school, but to the school of Godard, Massenet and Delibes rather than to that of Debussy and Ravel… Her music also shows traces of the influence of Chopin… However, Mlle. Chaminade has not the genius of Chopin. It is just salon music, but salon music of the most refined and pleasing kind. There is also a particularly feminine element about it just as there was about the music of Chopin.” Paderewski’s name is linked to a whole network of connections in the world of arts, and to the lives of various people, their accomplishments, and goals. As Zygmunt Stojowski wrote, “He was a great man thrice: through his own self, through his deeds and creations, and, finally, through the inspiration he gives unto others.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Cécile Chaminade: Etude symphonique, Op. 28 (Joanne Polk, piano)